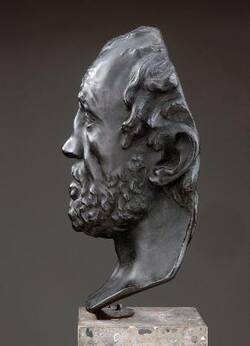

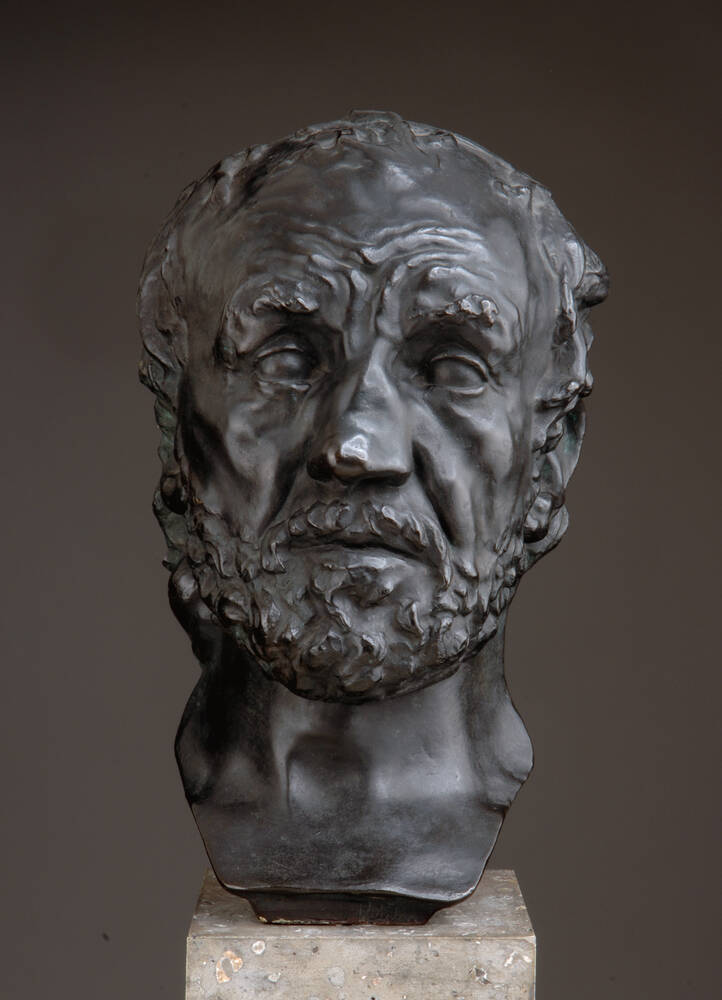

Ein Mensch aus Fleisch und Blut, die Haut gezeichnet vom Leben, mit Falten auf der Stirn, zerfurchten Wangen und mit der titelgebenden deformierten Nase. All dies weist auf ein bewegtes Leben hin. Rodins Menschen spiegeln zum ersten Mal in der Geschichte der Bildhauerei, dass ein Leben fragmentarisch, unvollendet und voller Brüche sein kann. Wer aber ist der Mann mit gebrochener Nase? Dazu die Kuratorin Astrid Nielsen:

„Dieses Bildnis, das heißt Bildnis M.B., es kann heißen, es steht dann für Monsieur Bibi, das war ein Arbeiter, der sich auf dem Pferdemarkt als Arbeiter verdingt hat und Rodin hatte sein erstes Atelier dort in der Nähe, das heißt, er hat ihm Model gesessen. Es gibt zu dieser Entstehung ne Anekdote, dass eben das Tonmodell runtergefallen ist und deswegen ist diese Nase so deformiert, das heißt, man weiß auch nicht, ob dieser Arbeiter tatsächlich so ne gebrochene Nase gehabt hat. Bildnis M.B. könnte aber auch heißen, Michelangelo Buonarroti, dessen Bildnis kennt man, ein Renaissancebildnis, das ihn darstellt, wo er eben selber ne gebrochene Nase hat.

Der italienische Renaissancebildhauer Michelangelo war für Rodin ein wichtiges Vorbild.

Übrigens war der „Mann mit gebrochener Nase“ das erste Werk von Auguste Rodin, welches von einem deutschen Museum angekauft wurde. Georg Treu, damals Direktor der Dresdner Skulpturensammlung, reiste 1894 nach Paris. Dort besuchte er Rodin in seinem Atelier und erwarb das Werk direkt von ihm. In Dresden wurde es sogleich der Öffentlichkeit präsentiert. Doch Rodins Werke waren zu jener Zeit durchaus nicht unumstritten. Mit seinen modernen Entwürfen stieß er immer wieder auf den Widerstand des konservativen Zeitgeistes. Denn er zeigt keine in die Ferne gerückten Helden, sondern nahbare Charaktere. Das gilt auch für dieses Werk.tirn, zerfurchten Wangen und mit der titelgebenden deformierten Nase. All dies weist auf ein bewegtes Leben hin. Rodins Menschen spiegeln zum ersten Mal in der Geschichte der Bildhauerei, dass ein Leben fragmentarisch, unvollendet und voller Brüche sein kann. Wer aber ist der Mann mit gebrochener Nase? Dazu die Kuratorin Astrid Nielsen:

„Dieses Bildnis, das heißt Bildnis M.B., es kann heißen, es steht dann für Monsieur Bibi, das war ein Arbeiter, der sich auf dem Pferdemarkt als Arbeiter verdingt hat und Rodin hatte sein erstes Atelier dort in der Nähe, das heißt, er hat ihm Model gesessen. Es gibt zu dieser Entstehung ne Anekdote, dass eben das Tonmodell runtergefallen ist und deswegen ist diese Nase so deformiert, das heißt, man weiß auch nicht, ob dieser Arbeiter tatsächlich so ne gebrochene Nase gehabt hat. Bildnis M.B. könnte aber auch heißen, Michelangelo Buonarroti, dessen Bildnis kennt man, ein Renaissancebildnis, das ihn darstellt, wo er eben selber ne gebrochene Nase hat.

Der italienische Renaissancebildhauer Michelangelo war für Rodin ein wichtiges Vorbild.

Übrigens war der „Mann mit gebrochener Nase“ das erste Werk von Auguste Rodin, welches von einem deutschen Museum angekauft wurde. Georg Treu, damals Direktor der Dresdner Skulpturensammlung, reiste 1894 nach Paris. Dort besuchte er Rodin in seinem Atelier und erwarb das Werk direkt von ihm. In Dresden wurde es sogleich der Öffentlichkeit präsentiert. Doch Rodins Werke waren zu jener Zeit durchaus nicht unumstritten. Mit seinen modernen Entwürfen stieß er immer wieder auf den Widerstand des konservativen Zeitgeistes. Denn er zeigt keine in die Ferne gerückten Helden, sondern nahbare Charaktere. Das gilt auch für dieses Werk.

Weitere Medien

Georg Treu, der damalige Direktor der Dresdner Skulpturensammlung, engagierte sich leidenschaftlich für Rodins moderne Plastiken, obwohl er kein Kunsthistoriker war – oder gerade weil er kein Kunsthistoriker war? Astrid Nielsen klärt auf:

„Georg Treu war Archäologe. Er kam 1881 nach Dresden und übernahm die Leitung der Skulpturensammlung, die damals noch bestand aus Antikensammlung und Abguss-Sammlung.“

Treu war an den Ausgrabungen in Olympia beteiligt gewesen. In Dresden sollte er ein neues Skulpturen-Museum eröffnen. Seine erste Amtshandlung betraf die Antikensammlung:

„Denn diese Antiken waren zur Zeit des Barock alle vervollständigt worden. Das war eine Hauptaufgabe der barocken Bildhauer, diese Antiken zu ergänzen. Der Blick, der archäologische, wissenschaftliche Blick hatte sich geändert zu der Zeit, als Georg Treu ausgebildet wurde als Archäologe, und nun kam er nach Dresden und entfernte all diese barocken Ergänzungen von den antiken Statuen.“

Drei Jahre später eröffnete Treu hier im Albertinum das neue Skulpturen-Museum. In der Folgezeit begann er, sich für zeitgenössische Werke zu interessieren.

„Es war zu der Zeit tatsächlich so, dass gerade die Skulptur in Frankreich besondere Erfolge feierte, und er hatte einen Kontaktmann in Paris, es war ein sächsischer Adliger, der dort an der Botschaft beschäftigt war, den kontaktierte er und schickte ihn in unterschiedliche Ateliers von Künstlern. So entstanden die ersten Kontakte zu Auguste Rodin.“

Treu war von Rodins Kunst spontan begeistert. Er hatte sein Auge an den Fragmenten antiker Skulpturen geschult; das Fragmentarische ist aber auch ein wesentliches Merkmal der Werke Rodins:

„Und dieses Verständnis für den Umgang Rodins mit einzelnen Fragmenten, mit Körperteilen, mit dem Herauslösen bestimmter Figuren aus Werkzusammenhängen, aus ganzen Gruppen, dieses Verständnis dafür entstand sicherlich bei Georg Treu aus seinem Umgang mit der antiken Kunst und mit dem besonderen Verständnis für Körperfragmente.“

A man of flesh and blood – yet from his wrinkled forehead to the deep furrows of his cheeks and his eponymous broken nose, his face clearly bears the traces of the years. Those features suggest an eventful life. For the first time in the history of sculpture, Rodin’s figures reflect the idea of a person’s biography being incomplete, fragmentary, full of twists and turns. But who was the man with the broken nose? Here’s curator Astrid Nielsen:

“This portrait is known as portrait M.B. – initials which could stand for Monsieur Bibi, a workman at the horse market. Since Rodin’s first studio was close by, Bibi may have sat as the model for this bust. But there’s also an anecdote about this work. According to that story, the nose is out of shape because the clay model for the sculpture accidentally fell on the ground. In other words, no one can know if Monsieur Bibi really had a broken nose or not. But the initials in Portrait M.B. might also stand for Michelangelo Buonarroti. There is, after all, a well-known Renaissance portrait of Michelangelo with just such a broken nose.

That renowned Italian Renaissance artist and sculptor was one of Rodin’s most important sources of inspiration.

Incidentally, the Man with the Broken Nose was the first of Rodin’s works bought by a German Museum. In 1894, Georg Treu, then Director of the Dresden Sculpture Collection in the Albertinum, travelled to Paris. He visited Rodin in his studio and acquired the work directly from him. In Dresden, it was immediately put on public show. But at that time, Rodin’s works were quite controversial. With his modern designs, he often found himself at odds with the conservative zeitgeist of his day. After all, he did not depict distant heroic figures, but very much flesh-and-blood people – just as he has done in this work.

Although not an art historian Georg Treu, then Director of the Dresden Sculpture Collection, was a fervent advocate of Rodin’s modern sculptures – or was Treu’s support for Rodin precisely because he was not an art historian? Astrid Nielsen explains:

“Georg Treu was an archaeologist. When he came to Dresden in 1881, he took over as head of the sculpture collection which, at that time, still comprised the antiquities collection and the collection of plaster casts.”

Treu had been involved in the excavations in Olympia. In Dresden, his tasks included opening a new museum for sculpture. The first thing he did when he took office was to modernise the collection of antiquities:

“During the Baroque period, the missing parts of these ancient statues had all been replaced. One of the principal tasks of Baroque sculptors was to complete damaged ancient sculptures. But when Georg Treu was training as an archaeologist, the scholarly, archaeological approach had changed totally – so he came to Dresden and removed all the Baroque additions to the ancient statues.”

Three years later, Treu opened the new Sculpture Museum here in the Albertinum. In the following years, he began to be interested in contemporary art works.

“In those days, in particular, sculpture in France was really making waves. Treu was friendly with a member of a noble Saxon family who was working at the Paris embassy. So Treu got in touch and sent him off to visit a wide range of artists’ studios there – and that was his first contact to Auguste Rodin.”

Treu was immediately enthusiastic about Rodin’s art. His eye had been trained by studying fragments of ancient sculptures – and the fragmentary is also an essential feature of Rodin’s work:

“Treu could appreciate Rodin’s treatment of individual fragments or parts of bodies, and how particular figures were dissolved from the work’s context, separated from an entire group. No doubt, Treu’s appreciation came from dealing with classical art and his readiness to accept and understand fragmentary bodies.”

Člověk z masa a krve, pleť poznamenaná dlouhým životem, s vráskami na čele, zbrázdělými tvářemi a deformovaným nosem, který portrétu dal jméno. To vše svědčí o pohnutém životě portrétované osoby. V Rodinových postavách se poprvé v dějinách sochařství odráží skutečnost, že život může zůstat fragmentární, nedokončený a plný zlomů. Kdo je ale tento muž se zlomeným nosem? O tom vypráví kurátorka Astrid Nielsenová:

"U tohoto portrétu, Rodinem občas označovaného jako "Portrét M.B.", se možná jedná o "Monsieura Bibi" - tedy pana Bibiho, který si na živobytí vydělával jako nájemní dělník na koňském trhu. Rodin tam měl nedaleko svůj první ateliér, a pan Bibi mu prý seděl modelem. O vzniku portrétu se traduje jedna historka, podle které model z hlíny spadl na zem a proto je nos tak zdeformovaný. To znamená, že opravdu nevíme, zda muž sedící modelem takto zlomený nos měl nebo ne. "Portrét M.B." ale také může znamenat "Michelangelo Buonarroti", o kterém na základě jednoho soudobého renesančního portrétu víme, že zlomený nos opravdu měl.

Italský renesanční sochař Michelangelo byl pro Rodina důležitým vzorem.

Mimochodem byl "Muž se zlomeným nosem" Rodinovým prvním dílem, které koupilo německé muzeum. Georg Treu, tehdejší ředitel sbírky drážďanský soch, cestoval v roce 1894 do Paříže, kde navštívil Rodina v jeho ateliéru a dílo koupil přímo od něj. V Drážďanech byl portrét hned vystaven pro veřejnost. Rodinovy práce však v té době nebyly nesporné. Jeho moderní návrhy opakovaně narážely na odpor konzervativních současníků, neboť Rodina nezajímali hrdinové mířící do vzdálené budoucnosti, nýbrž postavy zobrazující nám blízké a důvěrné pocity. To také platí i pro toto dílo.

Georg Treu, tehdejší ředitel drážďanské sochařské sbírky, byl vášnivým zastáncem Rodinových moderních plastik, přestože nebyl historikem umění – nebo možná také právě proto? Astrid Nielsenová upřesňuje:

„Georg Treu byl archeolog. Do Drážďan přišel roku 1881 a převzal správu sochařské sbírky, ke které tehdy ještě patřily sbírky antických soch a sbírky odlitků.“

Treu se podílel na vykopávkách v Olympii a v Drážďanech měl otevřít nové muzeum sochařského umění. Jako první věnoval svou pozornost sbírce antických soch:

„Všechna tato díla byla totiž v době baroka dokončena nebo spíš doplněna. Jedním z hlavních úkolů barokních sochařů bylo torza a neúplné plastiky doplnit. Pohled archeologů, tedy jejich vědecký přístup k sochám se v době, kdy Georg Treu archeologii studoval, změnil. A nyní přišel Treu do Drážďan a nechal všechny barokní doplňky z antických soch odstranit.“

O tři roky později v Albertinu otevřel nové muzeum sochařského umění. Poté se začal zajímat o tvorbu současných umělců.

„V té době se ve Francii velké pozornosti těšilo právě sochařství, které slavilo velké úspěchy, a Treu měl v Paříži kontakt na jednoho saského šlechtice, který byl zaměstnán na tamním velvyslanectví. Obrátil se na něj a poslal ho do různých uměleckých ateliérů. Tak byly navázány první kontakty s Augustem Rodinem.“

Treu byl Rodinovým uměním velmi nadšen. Jeho pohled byl vyškolen na antických sochách, z nichž se většina zachovala pouze jako torzo nebo jen jejich malá část. A právě tato fragmentárnost je také podstatným rysem Rodinových děl:

„Georg Treu velmi dobře porozuměl, jak Rodin zacházel s jednotlivými fragmenty, s jednotlivými částmi těla, s tím, jak vyčleňoval určité figury z kontextu díla či z celých skupin, neboť se sám zabýval antickým uměním a měl velký cit pro jednotlivé fragmenty.“

- Ort & Datierung

- 1863/64

- Material & Technik

- Bronze

- Dimenions

- H: 39,5 cm, B: 19,5 cm, T: 15,5 cm

- Museum

- Skulpturensammlung

- Inventarnummer

- ZV 1288