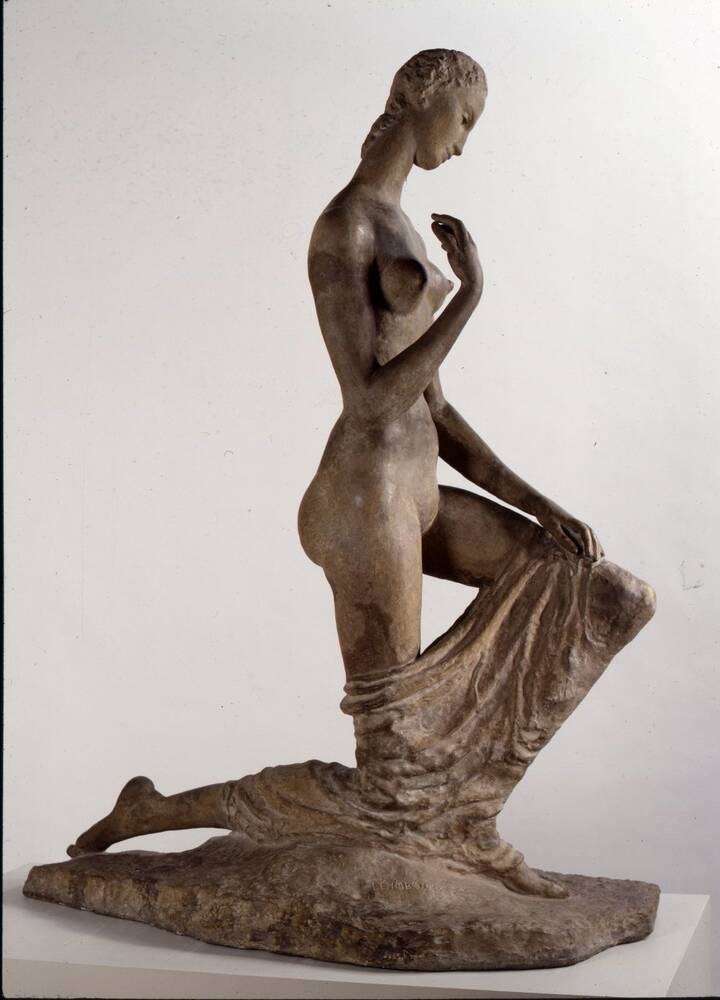

Der Kopf: seitwärts nach unten geneigt. Die Augen: geschlossen. Der rechte Arm angewinkelt, die rechte Hand vor der Brust – eine beinahe demütige Geste. Weltvergessen, ganz bei sich.

Wilhelm Lehmbruck schuf die "Kniende" 1911 in Paris. Dort hatte er sich intensiv mit den Werken Auguste Rodins und Aristide Maillols auseinandergesetzt und schließlich seine eigene Formensprache entwickelt. Die Kuratorin Astrid Nielsen über die "Kniende":

"Wenn sie sich erheben würde, wäre sie 2 Meter 22 groß, so ungefähr, und er hat sie dann eben auch ausgestellt, präsentiert, sie war ebenso umstritten, weil natürlich auch diese Überlängung der Gliedmaßen sehr infrage gestellt worden sind, weil sich das von den natürlichen Körperformen entfernt hat."

Lehmbruck ging es aber nicht um ein Abbild der natürlichen Körperformen:

"was eben auch hier neu ist, was in der Idee bei Rodin schon angelegt ist, ist die sogenannte Ausdrucksplastik. Das heißt, diese Figuren stehen tatsächlich nur noch für sich und das, was sie aussagen wollen."

Die Kniende ist nicht aus Stein gemeißelt, sie ist aus Stein gegossen, eine Technik, die in Frankreich damals beliebt war. Beim Steinguss wird pulverisierter Stein mit Zement und Wasser vermischt und in eine Negativform gegossen. Nach dem Aushärten wird der Guss aus der Form gelöst und nachbearbeitet. Auf diese Weise kann eine Skulptur mehrmals hergestellt werden. Die Kniende, die Sie hier sehen, entstand 1920, als Lehmbruck bereits verstorben war. Sie ist der einzige Steinguss der Knienden, den es hier in Europa noch gibt.

Weitere Medien

Am 19. Juli 1937 eröffneten die Nationalsozialisten in München die Ausstellung "Entartete Kunst". Dort präsentierten sie in diffamierender Weise 650 Kunstwerke der Moderne, die sie zuvor in deutschen Museen beschlagnahmt hatten. Kurz darauf folgte eine weitere, weitaus umfangreichere Beschlagnahmungs-Welle, der auch Lehmbrucks "Kniende" zum Opfer fiel. Astrid Nielsen über das Geschehen in Dresden:

„Tatsächlich wurden dann im September 1937 auch in Dresden verschiedene Skulpturen als sogenannte "entartete Kunst" beschlagnahmt. Das war nicht so umfangreich wie in anderen Museen, die Gründe dafür sind sehr vielfältig. Es mag daran gelegen haben, dass der damalige Direktor möglicherweise Kunstwerke versteckte, dass den Kommissionen der Zugriff auf Inventare verweigert wurde, und so wurden tatsächlich in Dresden nur elf Skulpturen beschlagnahmt. Dazu gehörten Werke von Ernst Barlach beispielsweise, Bernhard Hoetger und auch drei Skulpturen von Wilhelm Lehmbruck.“

Die stark überlängte, expressionistische Figur der Knienden widersprach dem Kunstverständnis der Nazis zutiefst:

„Die Nationalsozialisten hatten ein besonderes Verständnis von Kunst, es sollte der – natürlich – nordische Mensch propagiert werden, ein bestimmtes Körperbild, das Ideal eines Menschen, was aber nicht heißt, dass sie nicht wussten, dass es sich um wertvolle Dinge handelte.“

Die Nationalsozialisten planten, durch den Verkauf der beschlagnahmten Werke Devisen zu erwirtschaften. Lehmbrucks Kniende wurde daher zunächst nach Berlin transportiert, in ein Depot im Schloss Schönhausen. Im Anschluss wurde der Steinguss über den Schweizer Kunsthandel in die Vereinigten Staaten verkauft.

„Dort gelangte dieses Werk in verschiedene amerikanische Privatsammlungen, und gelangte 1993 wieder auf den Kunstmarkt, so dass es gelang, dieses Werk nach über 60 Jahren wieder für die Skulpturensammlung der Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen zurückzuerwerben.“

Her head is turned to one side, looking down. Her eyes are closed. Her right arm is bent, her hand in front of her breast – almost a gesture of humility. She seems entirely self-absorbed, oblivious of the world around her.

Wilhelm Lehmbruck’s sculpture dates from 1911. At that time he was living in Paris. He had intensively studied works by Auguste Rodin and Aristide Maillol, but was already moving away from their influence to create his own formal vocabulary. Listen to curator Astrid Nielsen on Lehmbruck’s Woman Kneeling:

"If this figure were to stand up, she would be around 222 centimetres – over seven feet tall. So when Lehmbruck first showed this work, it was very controversial. And since the figure’s elongated limbs are miles away from our natural anatomy, they came in for a lot of criticism.”

But Lehmbruck was not interested in a mimetic copy of natural body shapes.

“What is also new here is the idea – already inherent in Rodin – of expressionist sculpture. In other words, these figures only represent themselves and what they want to say.”

Lehmbruck’s Woman Kneeling is not carved in stone, but cast in stone – a technique extremely popular in France at that time. For a stone cast, crushed stone is mixed with water and cement and poured into a negative mould. After hardening, the cast is removed from the mould and finished by hand. The stone cast technique allows numerous copies of a sculpture to be made. The Woman Kneeling on show here was actually cast in 1920, the year after Lehmbruck died. This is the only stone cast Woman Kneeling still in Europe.

On 19 July 1937, the Nazi regime opened the “Degenerate Art” exhibition in Munich. The show presented and defamed 650 modern art works which the Nazis had previously confiscated from museums across Germany. Shortly afterwards, Lehmbruck’s Kneeling Woman fell victim to a second, much larger wave of confiscations. Astrid Nielsen on the events in Dresden:

“In September 1937, various sculptures were also confiscated in Dresden as so-called “degenerate art”. Fewer works were taken than in other museums – for diverse reasons. It might have been due to the director at that time possibly hiding art works or refusing the commissions access to the inventories. In any case, only eleven sculptures were seized from the Dresden collection. The pieces confiscated included, for instance, works by Ernst Barlach, Bernhard Hoetger, and three sculptures by Wilhelm Lehmbruck.”

Lehmbruck’s elongated, expressionist figure of a kneeling woman fundamentally went against the style of art advocated by the Nazi regime:

“The Nazis had a particular notion of art. Of course, in their view art should propagate the Nordic type, a specific physique, an ideal human being – but this does not mean they were blind to the monetary value of other art works.”

The Nazi regime planned to sell the confiscated works to generate foreign currency. So Lehmbruck’s Kneeling Woman was first taken to Berlin and placed in storage in Schönhausen Palace. Afterwards, the cast stone statue was sold to America via the Swiss art market.

“This work passed through several private collections in America. In 1993, it reappeared on the art market. And so over sixty years after the statue was confiscated, it was possible to reacquire it for the SKD’s Sculpture Collection.”

Hlava: skloněná na stranu dolů. Oči: zavřené. Pravá paže ohnutá tak, že ruka spočívá před hrudníkem - téměř pokorné gesto. Plně ponořená do svých myšlenek, mimo svět.

Wilhelm Lehmbruck vytvořil sochu "Klečící" roku 1911 v Paříži, kde se intenzívně zabýval dílem Augusta Rodina a Aristida Maillola a kde nakonec vyvinul svůj vlastní styl a našel svůj výraz. Kurátorka Astrid Nielsenová o soše "Klečící":

"Kdyby vstala, byla by přibližně velká dva metry 22. Když byla socha vystavena a prezentována veřejnosti, názory se o tomto díle velmi rozcházely, a velké diskuze vyvolávaly právě nepoměrně dlouhé končetiny, protože v žádném případě neodpovídaly přirozeným proporcím těla."

Lehmbruckovým záměrem však nebylo zobrazit realistické lidské tělo:

"co je tu nové a co vidíme už také u Rodinova díla, je tzv. sochařství výrazu. To znamená, že sochy reprezentují vpodstatě pouze sebe samé a to, co chtějí vyjádřit."

Socha "Klečící" není vytesána z kamene, ale je odlita z umělého kamene. Tato technika byla tenkrát ve Francii velmi oblíbena. Při tom se kamenný prach smíchá s cementem a vodou a poté se směs lije do negativní formy. Když vytvrdne, odlitek se z formy vyjme a dopracují se detaily. Tímto způsobem je možné sochařské dílo odlít několikrát. Socha, kterou vidíte zde, byla odlita roku 1920, již po Lehmbruckově smrti, a je jediným, v Evropě zachovaným kamenným odlitkem "Klečící".

Dne 19. července 1937 uspořádali v Mnichově nacisté výstavu pod názvem „Zvrhlé umění“ – německy „Entartete Kunst“, kde ponižujícím a potupujícím způsobem prezentovali 650 moderních uměleckých děl, která předtím zabavili v německých muzeích. Krátce potom následovala další, mnohem rozsáhlejší vlna, během níž nacisté zabavili kromě tisíce jiných děl také Lehmbruckovou sochu „Klečící“. Astrid Nielsenová o tom, co se v Drážďanech událo:

„V září 1937 byla také v Drážďanech zabavena různá sochařská díla jako tzv. „zvrhlé“ či „degenerované“ umění, nebylo však zabaveno tolik děl jako v jiných muzeích. Důvody proto jsou různé. Jedním z nich bylo možná, že tehdejší ředitel některé ze soch schoval nebo že komisím odepřel přístup ke všem inventářům. A tak bylo v Drážďanech skutečně zabaveno pouze jedenáct soch. Mezi ně patřila díla od Ernesta Barlacha, Bernharda Hoetgera a také tři sochy Wilhelma Lehmbrucka.“

Expresionistická postava klečící ženy, jejíž proporce jsou silně prodloužené, stála v hlubokém rozporu s nacistickým chápáním umění:

„Nacisté měli velmi specifickou představu o umění. To mělo zobrazovat – jak jinak – nordický typ člověka, určitý obraz lidského těla, jeho ideál, jak si jej představovali sami. To ale neznamená, že nacisté nevěděli, že se u zabaveného umění jedná o cenná díla.“

Nacisté plánovali, že prodejem zabavených děl získají devizové prostředky. Lehmbruckova „Klečící“ byla proto nejdříve převezena do Berlína, do depozitáře v zámku Schönhausen, a později byla prostřednictvím švýcarských obchodníků s uměním prodána do Spojených států.

„Tam toto dílo postupně patřilo různým americkým soukromým sběratelům a roku 1993 bylo znovu nabídnuto na trhu s uměním, takže bylo po více než 60ti letech možné jej získat do sbírky sochařského umění ve Státních uměleckých sbírkách.“

- Ort & Datierung

- Modell 1911, Guss nach der originalen Form 1920

- Material & Technik

- Steinguss (englischer Zement)

- Dimenions

- H: 179,0 cm, B: 68,5 cm, T: 140,0 cm

- Museum

- Skulpturensammlung

- Inventarnummer

- ZV 2840