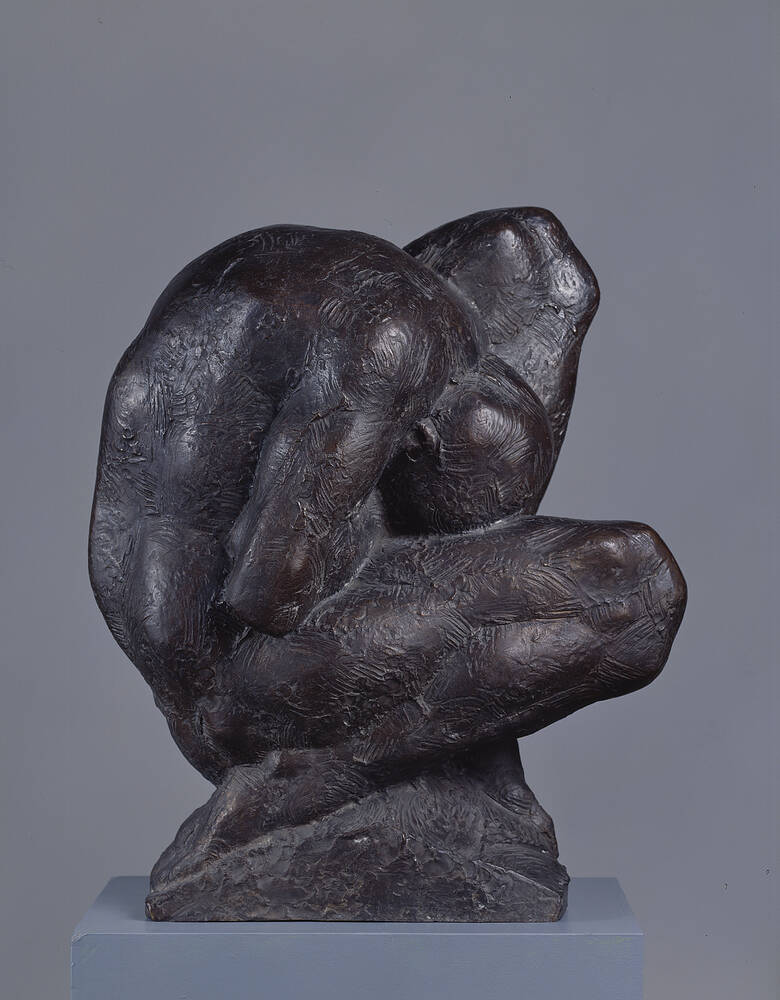

Als 15-Jähriger musste Wieland Förster die Bombardierung Dresdens miterleben. Nach dem Krieg saß er wegen angeblichen Waffenbesitzes vier Jahre unschuldig in Haft. Er sah Menschen sterben und litt selbst Todesangst. Danach wollte er Zeugnis ablegen. Er wollte den „unmenschlich Dahingemordeten“ mit seiner Kunst ein Denkmal setzen. Als Wieland Förster 1989 den „Geschlagenen“ schuf, ahnte er nicht, dass diese Figur Jahre später in Leipzig zu einem Denkmal im wahrsten Sinne werden würde: zur Erinnerung an die Sinti und Roma, die von den Nationalsozialisten getötet wurden.

Die Haltung der zusammengekauerten Figur verkörpert Schmerz, Angst und Verzweiflung. Ihre runden, muskulösen Formen aber strahlen eine Energie aus, die ungebrochen scheint. Diese Ambivalenz ist charakteristisch für Försters Bild vom Menschen, das bei allem Leid immer auch etwas Kraftvolles, Vitales, Lebensbejahendes hat.

Ein Schlüsselerlebnis im Jahr 1960 hatte ihm bei der Suche nach einer Ausdrucksform für sein Menschenbild geholfen: Eines Nachts sah er ein Mädchen, das über ihm auf einer Treppe stand und mit erhobenem Kopf den Mond betrachtete. Förster nahm ihren Kopf als ei-förmiges Oval wahr. Die Erkenntnis war so stark, dass er fortan dieser Form vertraute und sie zum Grundelement seines Schaffens machte. Besonders deutlich sehen wir das beim „Kopf der Gelähmten“, dem Porträt einer Frau, die in unmittelbarer Nachbarschaft des Bildhauers in Berlin lebte. Wieland Förster bewunderte, wie diese Frau trotz aller Einschränkungen ihr Leben meisterte:

„Für sie war das Heizen ihres Ofens gefahrvoller als die Leistung vieler bestaunter ‚Helden‘. Und das ist es, was mich besonders interessiert“.

Wieland Förster war ein erfolgreicher Bildhauer, obwohl er nicht immer systemkonform gearbeitet hat. Sein „Kopf der Gelähmten“ und andere Leidensdarstellungen widersprachen dem geforderten optimistischen Menschenbild und brachten Förster 1968 ein Arbeits- und Ausstellungsverbot ein. In den 70er Jahren wurde er rehabilitiert.

Weitere Medien

„Wir stehen hier in der Skulpturenhalle. Hier wird die Geschichte der modernen Skulptur erzählt von Auguste Rodin bis zur Gegenwart. Die moderne Bildhauerei beginnt tatsächlich mit Rodin. Den erwähne ich, weil er in gewisser Weise ein Bezugspunkt ist für die Bildhauerei, die sich in der DDR nach 1945 entwickelt hat. Es gibt auch andere Bezüge, andere Vorläufer, andere Bildhauer, auch französische Bildhauer wie Aristide Maillol, den wir hier auch ausgestellt haben, auf den sich die Bildhauer im Osten Deutschlands bezogen haben.

Es gibt einen grundlegenden großen Unterschied zur Bildhauerei, die sich im Westen Deutschlands entwickelt hat, weil man im Osten an der menschlichen Figur festhielt. Das wurde nach 1945, nach der großen Katastrophe des Jahrhunderts, im Westen Deutschlands als nicht mehr möglich angesehen, ein heiles Körperbild darzustellen. Die Bildhauerei entwickelte sich also unterschiedlich: nicht figürlich im Westen und sie blieb figürlich im Osten Deutschlands. Die abstrakte Kunst galt zunächst als formalistisch, direkt nach 1945, als dekadent. Das sind Vorwürfe, die auch der Malerei gemacht wurden in den frühen Jahren der DDR. Was man anstrebte, war natürlich die Darstellung eines gewissen neuen Menschenbildes, das die DDR als programmatisch erachtete: das Bild des Arbeiters. Der sozialistische Realismus entstand später – und das bezog sich in Teilen auch auf Bildhauerei.“

When he was 15, Wieland Förster experienced the bombing of Dresden. After the war, he was accused of possessing weapons and, although he was innocent, spent four years in prison. He saw people dying and also feared for his own life – and afterwards he wanted to testify to what he had seen, to use his art as a memorial for those so ‘inhumanely murdered’. When Wieland Förster created his sculpture Beaten Man in 1989, he had no idea that years later this figure would literally become a memorial in Leipzig – to commemorate the Sinti and Roma murdered under the Nazi regime.

Although the pose of the cowering, crouching figure embodies pain, fear and despair, the round muscular shapes radiate a seemingly unbroken energy. Such an ambivalence is characteristic of Förster’s image of people which, despite the suffering, always has something powerful, energetic, and life-affirming.

In 1960, he had a crucial experience in his quest to express his view of the human figure. One night he saw a young woman standing above him on a staircase, her head lifted to gaze at the moon. From his perspective, her head appeared as an egg-shaped oval form. His discovery was so vivid and powerful, he adopted the shape as a touchstone and fundamental element in his oeuvre. It is especially prominent in his Head of the Paralysed Woman – a portrait of a woman who lived near him in Berlin. Wieland Förster admired her for the way she managed her life, despite all her limitations:

“For her, lighting the stove was more difficult and dangerous than the achievements of many acclaimed ‘heroes’. And that is what interested me especially.”

Wieland Förster was successful as a sculptor, even though his works did not always conform to the precepts of art approved in the GDR. For instance, his Head of the Paralysed Woman and other depictions of suffering contradicted the officially sanctioned optimistic image of the human figure. In 1968, this led to Förster being banned from working as an artist and exhibiting. He was later rehabilitated in the 1970s.

“We are in the Sculpture Hall. where our display presents the history of modern sculpture from Auguste Rodin to the present day. Modern sculpture has its origins in Rodin’s works – which is worth mentioning here since, in a certain way, he was a point of reference for sculpture as it developed in the GDR after 1945. The sculptors working in East Germany also had other sources of inspiration, other precursors, other sculptors they looked to – and also other French sculptors, such as Aristide Maillol, whose works are also on show here.

Sculptors in East Germany continued to base their work on the human figure – a fundamental and major difference to sculpture as it developed in West Germany. In the post-war years, after the twentieth century’s great catastrophe, West German sculptors felt it was impossible to create works depicting unscathed human figures. As a result, sculpture evolved differently in West and East Germany – as non-figurative in the former, and figurative in the latter. Directly after 1945, abstract art in eastern Germany was initially condemned as formalistic and decadent. This was an accusation similarly levied against abstract painting in the early years of the GDR, when the official aim of art was to depict a particular new human image regarded as programmatic in the GDR – the image of the worker. Socialist Realism developed later – and that development also partially applied to sculpture.”

Jako patnáctiletý zažil Wieland Förster bombardování Drážďan. Po válce byl čtyři roky nevinně vězněn za údajné držení zbraně. Viděl umírat lidi a sám poznal strach ze smrti. O tom chtěl podat svědectví a svým uměním postavit pomník „nelidsky zavražděným“. Když Wieland Förster v roce 1989 vytvořil „Zbitého“, netušil, že se jeho dílo o několik let později stane v Lipsku opravdovým pomníkem: a sice památníkem Sintů a Romů, kteří byli zavražděny nacisty.

Postava schouleně krčícího se muže ztělesňuje bolest, strach a zoufalství. Její oblý tvar a svalnaté tělo však vyzařují energii, která se zdá být neoblomná. Tato ambivalence je příznačná pro Försterovu představu člověka, který v sobě navzdory všemu utrpení skrývá vždy něco silného, vitálního a životadárného.

Klíčový zážitek z roku 1960 mu pomohl při hledání možnosti, jak vyjádřit svou představu člověka: Jedné noci uviděl dívku, která stála na schodišti nad ním a se vztyčenou hlavou pozorovala měsíc. Její obličej Försterovi připomínal ovál. Tento dojem se v něm zakořenil natolik, že se tvar oválu stal základním prvkem jeho práce. Zvlášť zřetelně to vidíme na díle „Hlava ochrnuté“, portrétu ženy, která žila hned ve Försterově sousedství v Berlíně. Wieland Förster obdivoval, jak tato žena navzdory všem svým omezením zvládala svůj život:

„Pro ni bylo topení v kamnech mnohem nebezpečnější než výkony mnoha obdivovaných tak zvaných „hrdinů“. A to je přesně to, co mě obzvlášť zajímá.“

Wieland Förster byl úspěšným a uznávaným sochařem, přestože ne vždy pracoval v souladu s vládnoucím systémem. Jeho „Hlava ochrnuté“ a jiná díla zobrazující utrpení byly v rozporu s požadovaným optimistickým obrazem člověka. Roku 1968 mu byl udělen zákaz práce a nesměl vystavovat. V sedmdesátých letech byl rehabilitován.

„Stojíme tu v sochařské síni. Zde můžeme sledovat vývoj moderního sochařství od Augusta Rodina až po současnost. Počátek moderního sochařství je skutečně spojeno s Rodinovým dílem. Zmiňuji se o něm, protože sochařství, které po roce 1945 vzniklo v bývalé NDR, se určitým způsobem vztahuje právě k jeho umění. Samozřejmě, že existují také i jiné vzory a další předchůdci a sochaři, kteří měli vliv na sochařské umění ve východním Německu, a patřili k nim také jiní francouzští sochaři jako například Aristide Maillol, jehož dílo jsme tu také vystavovali.

Mezi sochařským uměním ve východním a západním Německu existuje ale jeden zásadní a velký rozdíl, neboť na východě zůstala centrálním námětem lidská figura. V západním Německu bylo po roce 1945 a po do té doby největší katastrofě 20. století zobrazení zdravého lidského těla považováno za nemožné. Sochařské umění se tedy v obou zemích vyvíjelo odlišně: na západě nefigurativně a na východě zůstalo figurativní. Abstraktní umění bylo považováno za formalistické a bezprostředně po skončení války 1945 dokonce za dekadentní. Tato kritika byla v prvních letech existence NDR vznášena také vůči malířství. Umění mělo usilovat o zobrazení nové představy člověka, která odpovídala politickému programu NDR: obrazu dělníka. Socialistický realismus vznikl později – a ten se zčásti také týkal sochařství.“

- Ort & Datierung

- 1989 Guss vor 2002, Auflagenhöhe: 6

- Material & Technik

- Bronze

- Dimenions

- H: 71 cm, B: 36,5 cm, T 56,5 cm

- Museum

- Skulpturensammlung

- Inventarnummer

- WF 044