"Das Werk kennen Sie alle – jeder wird es kennen, es ist auf Briefmarken reproduziert, es ist das Bild der deutschen Klassik schlechthin. Schiller und Goethe vereint als Denkmal in Bronze in Weimar. Und wer ist der Bildhauer? Niemand weiß es."

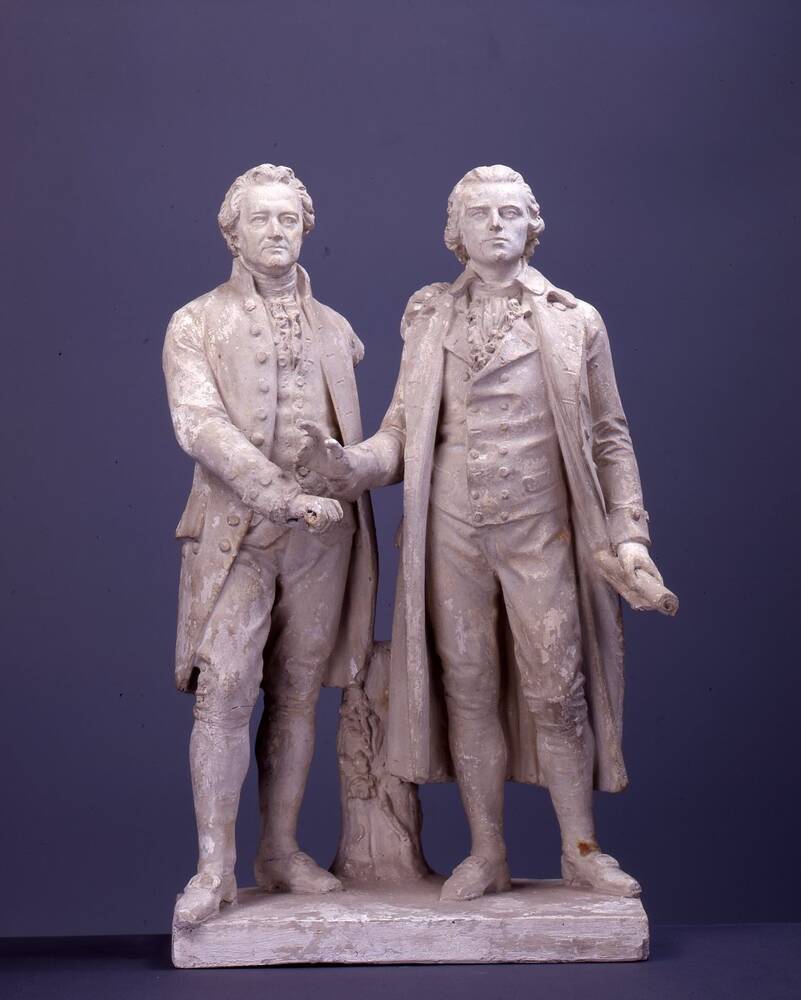

Die Kuratorin Astrid Nielsen kennt natürlich den Namen. Es ist der Dresdner Ernst Rietschel. Sie sehen hier seinen Entwurf zu dem berühmten Dichterdenkmal in Weimar. Er wurde genau so – natürlich als vergrößerter Bronzeguss – umgesetzt, nur fehlt bei dem Entwurf noch der Lorbeerkranz, den Goethe und Schiller bei dem fertigen Denkmal gemeinsam in Händen halten.

Rietschel war als Bildhauer sehr erfolgreich. Schon mit 28 war er Professor an der Dresdner Kunstakademie. Die Kommission, die das Goethe-Schiller-Projekt realisieren sollte, entschied sich aber dennoch zunächst für Rietschels Lehrer, den sehr viel berühmteren Christian Daniel Rauch in Berlin. Der Entwurf, den Rauch ablieferte, zeigte die Dichter, wie damals üblich, in antiken Kostümen:

"Es gab eine ganz traditionelle Darstellungsweise in der Denkmalskunst bis zu dem Zeitpunkt, und zwar wurden Herrscher, Könige immer in einem antikischen Gewand gezeigt. Also mit so einem antiken Mantel. Christian Daniel Rauch hat das eben auch noch angewandt in seinen Denkmalsentwürfen –"

aber Rauchs Entwurf kam nicht an, und die Aufgabe wurde 1852 an Rietschel übertragen. Wie Sie sehen, stellte er Goethe und Schiller in zeitgenössisch-bürgerlicher Kleidung dar, und auf Augenhöhe: Beide sind gleich groß. Hier hat Rietschel allerdings geschummelt: Tatsächlich war Schiller größer als Goethe.

Weitere Medien

„Das 19. Jahrhundert wird gemeinhin als DAS Jahrhundert der Denkmäler bezeichnet, in dem in vielen Städten an ganz zentralen Plätzen viele neue Denkmäler entstanden. Kannte man 1800 etwa in Deutschland 18 bis 20 große Denkmäler, waren es in den 1880er Jahren 800.“

So die Kuratorin Astrid Nielsen. Kritische Zeitgenossen sprachen seinerzeit von einer regelrechten Denkmal-Manie. Auf den Sockeln bekamen die ruhmreichen Herrscher zunehmend Konkurrenz:

„Es war etwas Neues im 19. Jahrhundert, nicht nur den Herrschern, den Königen, Denkmäler zu setzen, sondern auch Literaten, Musikern und anderen Geistesgrößen, das heißt, die Würdigung eines Lebenswerkes, was erworben wurde und was nicht angeboren war, war etwas Neues im 19. Jahrhundert. Das hängt zusammen mit der Zeit der Aufklärung, und natürlich auch mit einem aufkeimenden Demokratieverständnis, dass die politisch aktive Person, oder auch die Persönlichkeiten des kulturellen Lebens denkmalwürdig wurden.“

Ernst Rietschels Denkmal von Goethe und Schiller ist sein berühmtestes Werk, aber beileibe nicht sein einziges:

„Er hat viele Denkmäler geschaffen, nicht nur hier in Sachsen, sondern auch in Braunschweig beispielsweise das Lessing-Denkmal, das Luther-Denkmal in Worms. Er gehört mit zu den Gründern der sogenannten Dresdner Bildhauerschule, die in der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts führend war – gerade was Denkmalkunst betraf.“

Und nicht zuletzt setzte Rietschel mit seinen Denkmälern auch einen nachhaltigen Trend. Die Persönlichkeiten auf den Denkmälern trugen nun zeitgenössische Kleidung:

„Das kann man sehr gut sehen gerade am Schiller- und Goethe-Denkmal, das kann man am Lessing-Denkmal sehr gut sehen. Zuvor waren die Dargestellten immer in einen antiken Mantel gekleidet. Das schaffte Ernst Rietschel ab, wodurch er auch eine besondere Nähe der Dargestellten zum Betrachter schuf.“

“Everyone in Germany knows this work – as do many around the world. The two figures are the writers Goethe and Schiller. Unified together as a bronze monument in the city of Weimar, they epitomise the neo-classical movement in Germany. And who was the sculptor? No one knows his name.”

But naturally our curator Astrid Nielsen knows his name – Dresden sculptor Ernst Rietschel. Here, we are showing his preliminary model for the famous monument in Weimar. This model is almost identical to the final bronze cast – though, of course, the bronze is much bigger. The only difference in the design is the laurel wreath which, in the final version, Goethe and Schiller are jointly holding.

Rietschel was a highly successful sculptor. At just 28 years old, he was appointed as a professor at the Dresden Academy of Art. But initially, the committee for the Goethe-Schiller project favoured the design by Christian Daniel Rauch in Berlin. Not only had Rauch been Rietschel’s teacher, but he was also far more famous. As was common at that time, Rauch’s proposed design portrayed Goethe and Schiller in ancient Greek robes.

"There was very traditional approach to depicting figures in memorial art at that time, with rulers, kings and so on always shown in traditional drapery – the robes of the classical world. Christian Daniel Rauch still followed that principle in his designs for the memorial sculpture ...”

But the committee decided against Rauch’s design, and in 1852 commissioned Rietschel with the work. As you can see, he presented Goethe and Schiller in contemporary clothing and as equals – with both figures the same size. In fact, Rietschel cheated here a little bit, since in real life Schiller was taller than Goethe.

As curator Astrid Nielsen points out:

“The nineteenth century is generally described as THE century of monuments and memorials, a time when many new ones were set up on central squares in many cities. For example, we know of around 18 to 20 large memorials in Germany in 1800, but by the 1880s, that number had grown to 800.”

In those days, critical contemporaries called it nothing short of a monument mania. And renowned and glorious rulers found they needed to defend their place on the plinth against increasing competition:

“The new thing in the nineteenth century was that monuments and memorials were no longer solely for kings, queens and rulers, but also for luminaries in the worlds of literature, music, and so on – in other words, this was about honouring someone’s life’s work – not their inherited position, but what they had achieved. This novel idea was closely linked to the age of Enlightenment and also, of course, to a burgeoning notion of democracy where a person active in political life, or a leading light in culture and the arts, would be worthy of a memorial.”

Ernst Rietschel’s Goethe and Schiller Memorial is no doubt his most famous work, though it is far from his only one:

“Rietschel made numerous monuments and memorials, not just here in Saxony, but also, for example, the Lessing Memorial in Braunschweig, and the Luther Memorial in Worms. He is ranked as one of the founders of the Dresden school of sculpture, a leading movement in the mid-nineteenth century – especially in monumental sculpture.”

Moreover, in his monuments and memorials, Rietschel introduced an innovative and lasting trend – the figures depicted in his statues wore the costume of their own day.

“You can see this very easily in his Schiller and Goethe Memorial, as well as his Lessing Memorial. Previously, such figures were dressed in traditional drapery, those flowing ancient robes. Remarkably for his time, Ernst Rietschel abandoned that approach – and by adopting period costumes, created a special sense of closeness between the beholders and the figures.”

"Ten pomník jistě také znáte - každý ho zná. Je zobrazen i na poštovních známkách a je nejznámějším pomníkem německé klasiky vůbec. Schillerův a Goethův bronzový pomník ve Výmaru. Ale kdo je autorem pomníku? To neví nikdo."

Kurátorka Astrid Nielsenová jméno umělce a autora samozřejmě zná. Je jím Ernst Rietschel z Drážďan. Vidíte zde jeho návrh slavného pomníku obou básníků ve Výmaru, který byl přesně takto zrealizován - samozřejmě jako o mnoho větší bronzový odlitek. Na modelu chybí pouze vavřínový věnec, který Goethe a Schiller na hotovém pomníku společně drží v ruce.

Rietschel slavil jako sochař velké úspěchy. Již ve 28 letech byl na Drážďanskou akademii umění povolán jako profesor. Komise, která nesla odpovědnost za realizaci Goethova a Schillerova pomníku, se však nejdříve rozhodla požádat o návrh tenkrát o mnoho známějšího Rietschelova učitele, Christiana Daniela Raucha z Berlína. Rauch oba básníky na svém modelu znázornil v antickém oděvu, jak tenkrát bylo běžné:

"V tehdejším umění panoval - co se týče pomníků slavných osobností - velmi tradiční styl, panovníci a králové byli zobrazováni vždy v antickém oděvu. Christian Daniel Rauch zůstal ve svých návrzích této tradici věrný -"

ale Rauchův návrh nedorazil, a tak byl zakázkou pověřen roku 1852 Rietschel. Jak vidíte, oblékl Goetha a Schillera do dobového oděvu, a zobrazil je jako sobě rovné: Oba jsou stejně velcí. Rietschel zde však trochu švindloval: Ve skutečnosti byl totiž Schiller větší než Goethe.

„Devatenácté století je všeobecně označováno jako století pomníků, neboť v této době bylo postaveno v četných městech mnoho nových pomníků na centrálních místech. Zatímco kolem roku 1800 existovalo přibližně 18 až 20 velkých pomníků, v 80tých letech 19. století jich již bylo 800.“

Jak vypráví kurátorka Astrid Nielsenová. Kritičtí současníci tehdy hovořili o skutečné památkové mánii. A na kamenných podstavcích konkurovali slavným panovníkům i jiné osobnosti:

„To bylo něco nového: V 19. století se nestavěly pomníky pouze panovníkům a králům, ale také literátům, hudebníkům a jiným slavným osobnostem. Oslava a ocenění celoživotního díla, vlastního úsilí a ne zděděné moci – to bylo v 19. století nové. Toto novum souvisí s dobou osvícenství a samozřejmě také s rozvíjejícím se chápáním demokracie. Proto se pamětihodnými staly také politicky činné osobnosti nebo významné osobnosti z kulturního života.“

Goethův a Schillerův pomník je nejznámějším dílem Ernsta Rietschela, ale zdaleka není jeho jediným dílem:

„Vytvořil mnoho dalších pomníků, a to nejen zde v Sasku, nýbrž také například v Braunschweigu, kde stojí jeho Lessingův pomník, nebo ve Wormsu, kde se nachází pomník Martina Luthera. Rietschel byl jedním ze zakladatelů tzv. drážďanské sochařské školy, která v polovině 19. století zaujímala přední místo – právě v oblasti monumentálního umění.

Navíc měly Rietschelovy pomníky také dlouhodobý vliv na pozdější díla. Zobrazené osobnosti mají na pomnících dobové oblečení:

„Je to velmi dobře vidět právě na pomníku Goetha a Schillera. A stejně tak také na Lessingově pomníku. Osobnosti na pomnících byly dříve zobrazovány v antickém oděvu, většinou tunice. Rietschel tuto tradici opustil a přiblížil tak zobrazené divákovi, čímž mezi nimi vznikl zvláštní vztah.“

- Ort & Datierung

- 1852/53

- Material & Technik

- Gips

- Dimenions

- Gesamt: H: 56,2 cm, B: 35,3 cm, T: 20,8 cm

- Museum

- Skulpturensammlung

- Inventarnummer

- ASN 0061