„Ein kleines modernes Raubtier“.

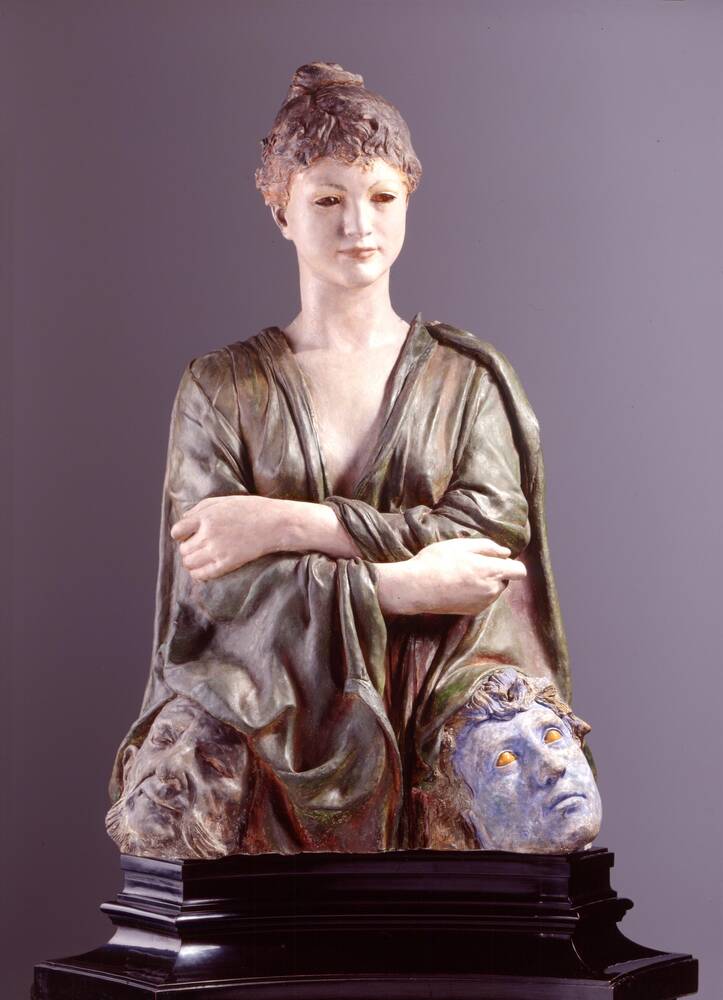

So urteilt im Jahr 1900 Georg Treu, der Leiter der Skulpturensammlung im Albertinum, über Max Klingers Skulptur "Die neue Salome". Sie sehen hier das von Klinger eigenhändig bemalte Gipsmodell. Treu beschreibt das Kunstwerk so:

„Wie gut passen ihre gefährlichen dunklen Augen, das eigenwillige Näschen, die kalten schmalen Lippen zu der Bewegung der Arme, die sich in naiv-grausamer Selbstgefälligkeit über den verzerrten Köpfen ihrer sterbenden Opfer kreuzen.“

In der Bibel erbittet Salome von König Herodes als Lohn für ihren verführerischen Tanz das Haupt von Johannes dem Täufer. Klinger deutet die Figur neu: Er macht aus ihr eine selbstbewusste, moderne Femme Fatale, die die Männer ins Verderben stürzt. Ein Frauenbild, das um 1900 populär ist, weil es den Zeitgeist trifft: Viele Männer fühlen sich damals von den zunehmend sich emanzipierenden Frauen bedroht. Vielleicht sogar auch Georg Treu?

Modern ist auch, dass Klinger seine Salome farbig bemalt. Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts gilt oft noch die Regel: "Skulpturen müssen weiß sein" – am besten aus strahlendem Marmor, wie die Statuen der Antike. Aber Klinger ist auf dem Laufenden. Er weiß, dass man auch an antiken Skulpturen Farbspuren entdeckt hat, und greift zum Pinsel: Die "neue Salome" gilt als Schlüsselwerk der farbigen Skulptur im ausgehenden 19. Jahrhundert. Und Klinger geht noch weiter, er wagt das Unerhörte – den Materialmix. Haben Sie entdeckt, dass seine Salome wunderschöne Augen aus Bernstein hat?

Weitere Medien

„Dresden galt zu Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts als ziemlich verschlafenes Zentrum der Kunst; es regierten lange Zeit die Geschmäcker der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, Nazarener, Romantik, und erst nach und nach gelang es, den jungen Kräften, vor allem in Dresden das Neue mit auch hier reinzubringen.“

Das Neue, von dem der Kurator Andreas Dehmer spricht, war vielgestaltig. Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts entwickelte eine junge Künstlergeneration höchst innovative Stilrichtungen: Impressionismus, Symbolismus, Jugendstil. Die neue Kunst war umstritten, fand aber auch im konservativen Dresden Anhänger. Einer der Direktoren der Dresdner Sammlungen erinnert sich:

„Es wetterleuchtete hier und da, und einige Hechte im Karpfenteich, zu denen namentlich auch die Direktoren der Kunstsammlungen gehörten, brachten eine wohltuende Beunruhigung in den bis dahin von keinem Windhauch gestreiften Wasserspiegel. Es tauchten Namen auf, von denen man vorher nicht gehört hatte: Böcklin, Uhde, Liebermann, Thoma, Klinger.“

Die Direktoren konnten allerdings nicht eigenmächtig über Ankäufe entscheiden:

„In der Ankaufskommission saß immer ein königlicher Spross, und der König selbst hatte auch durchaus seine Vorstellungen, was die Kunst betraf – nicht ganz so dezidiert wie Wilhelm der Zweite, der ja alles, was impressionistisch war, als Rinnsteinkunst bezeichnete. Da waren die Sachsen nicht ganz so erbittert. Allerdings fiel es wirklich auch schwer, neue Kräfte zuzulassen, also Max Klinger oder vor allen Dingen auch Arnold Böcklin. Da ging's teilweise mit in den Landtag hinein, da erfolgten bittere Debatten, was ist gute Kunst, was ist schlechte Kunst.“

Die Gipsfigur der „neuen Salome“ ist, wie gesagt, ein Modell. Nach ihrem Vorbild schuf Max Klinger später eine Marmorversion, die sich heute in Leipzig befindet, im Museum der Bildenden Künste. Die Restauratorin Stefanie Exner weist jedoch darauf hin, dass der Künstler auch das Gipsmodell als eigenes Kunstwerk ansah:

„Für den Künstler selbst ist das ein ganz eigenständiges Werk mit einer, wie er es nennt, „ziemlich komplizierten Bemalung“. Für diese Fassung, wie man auch sagen kann, experimentierte Klinger mit mehrlagig aufgetragenen, verschiedenfarbigen Schichten. Zum Beispiel liegt unter dem Grün des Gewands der Salome eine sichtbare krapprote Farbschicht. Oder unter der braunen Haarfarbe leuchten am Ansatz blaue Partien hervor.“

Klinger scheint die Farben selbst hergestellt zu haben. Er mischte die Pigmente mit unterschiedlichen Bindemitteln wie Öl, Wachs und Leim. Das aber sorgte bereits kurz nach der Herstellung für Probleme: Bestimmte Farbschichten hafteten schlecht aufeinander und es kam schon frühzeitig zu Verlusten. Als man 1994 daran ging, die Gipsfigur zu restaurieren, zeigte sich, dass 80 Prozent der Bemalung des Gesichts verloren war; bei den Gewandpartien fehlten etwa 30 Prozent. Die Farbschichten sollten möglichst originalgetreu ergänzt werden.

„Doch wie kann das gehen, wenn es keine exakten Angaben oder Fotos gibt. Als Vorlage für die Retuschen dienten zumindest die besser erhaltenen Hände. Verbliebene Reste der Augenschattierung, der Brauen oder des Lippenrots sollten sichtbar bleiben. Sie erhielten nur eine sparsame Verstärkung. Das Ergebnis, wie man es heute sieht, ist ein geschlossen farbiges Bild, ja, aber es trügt.“

Wie Klinger das Gesicht der Salome tatsächlich bemalt hat, lässt sich nicht mehr rekonstruieren.

In 1900, when Georg Treu, Director of the Dresden Sculpture Collection in the Albertinum, saw Max Klinger’s The New Salome, he is said to have commented:

“A modern little predatory creature.”

Here, you can see Klinger’s plaster model painted by his own hand. In Georg Treu’s words:

“How well her dangerous dark eyes, headstrong little nose, and cold narrow lips match the position of her arms, crossed with a smug naïve cruelty over the distorted heads of her dying victims.”

In the biblical story, Salome performs a seductive dance for King Herod. As a reward, she asks for the head of John the Baptist. But Klinger has reinterpreted the biblical Salome, transforming her into a self-confident, modern femme fatale, bringing disaster on the men around her. Around 1900, this was a popular trope of women resonating with a zeitgeist when many men felt threatened by women’s growing success in their fight for political and social rights. Might that also have been true for Georg Treu?

Klinger’s Salome sculpture is also painted – another example of his modern approach. In the late nineteenth century, the cry was often, ‘sculptures have to be white’ – best of all, in brilliant marble, echoing those statues known from classical world. But Klinger was up on the latest developments. He knew that ancient sculptures had also been found bearing traces of colour – and he reached for his paints. Klinger’s New Salome is considered a key work of painted sculpture in the late nineteenth century. But Max Klinger also dared to do something unheard of – mixing materials. Have you noticed Salome’s wonderful eyes are made of amber?

“At the end of the nineteenth century, Dresden was seen as rather a sleepy centre of the arts. For a long time, prevailing taste remained fixed on the styles of the first half of the 1800s, with the Nazarene and Romantic artists. The fresh generations only gradually managed to introduce new developments, in particular, in Dresden as well.”

The novel approaches mentioned by curator Andreas Dehmer came in many forms. The young artists in the late 1800s produced highly innovative styles of art – Impressionism, Symbolism, and Jugendstil, the German counterpart to Art Nouveau. These new art movements were controversial, but they also found adherents in conservative Dresden. One of the directors of the Dresden Collections recalled:

“There were flashes of lightning here and there and, to its great benefit, some of the big fish in this pond – including directors of the art collections – stirred up a surface previously unruffled by even the slightest breath of wind. And the names which emerged were ones never heard before: Böcklin, Uhde, Liebermann, Thoma, Klinger.”

But directors were not empowered to take unilateral decisions on acquisitions.

“One of the royal offspring always sat on the Acquisitions Commission and, when it came to art, the King himself certainly had his own ideas – not quite as forceful as Wilhelm II, the German Emperor, who described all Impressionism as the ‘art of the gutter’. The views in Saxony were not quite as intransigent. Admittedly, though, it proved very difficult to have new developments accepted, such as the art of Max Klinger or, above all, Arnold Böcklin. In some cases, such matters even reached the Saxony state parliament, where they triggered fierce and bitter debates on what is good and bad art.”

As was already mentioned, Klinger’s New Salome is a plaster model. Later, Max Klinger made a version in marble – today in the MdbK, the Museum of Fine Arts in Leipzig. But as restorer Stefanie Exner points out, Klinger also viewed this plaster model as an art work in itself:

“For the artist himself, this is a totally independent work which, as he said, has been decoratively painted in a ‘rather complex way’. So in this version, as we could say, Klinger experimented with different colours applied in a number of layers. For example, a layer of madder red is visible under the green of Salome’s gown. Similarly, along the hairline, blue elements shimmer through under the brown hair.”

Klinger appears to have made the colours himself, mixing the pigments with various bonding agents, such as oil, wax, and lime paste. But this resulted in various problems, even soon after Klinger finished painting the work. Some layers of colour did not bind well, which led to colour loss even in those early days. When restoration work started on the plaster figure in 1994, over 80 per cent of the facial painting had been lost as well as around 30 per cent of the colours on the gown. The restoration work aimed at supplementing the colour layers as faithfully as possible.

“But how can you do that without any precise information or photos? The hands, at least, were in a better condition, and they served as a basis for retouching the paint. The idea was to leave the remnants of shading around the eyes visible, as well as the eyebrows, and the red of the lips. So these parts were only minimally strengthened. As you now see, the result is a unified painted image – but, yes, to a certain extent, this is also deceptive.”

Today, we can no longer reconstruct how Klinger actually painted Salome’s face.

"Malé moderní dravé zvíře".

To roku 1900 o soše "Nová Salome" od Maxe Klingera prohlásil ředitel sbírky soch v Albertinu. Můžete si zde prohlédnout sádrový model sochy, který Klinger vlastnoručně barevně napatinoval. Treu umělecké dílo popisuje následovně:

"Jak dobře se její nebezpečné tmavé oči, její umíněný nosík a chladné úzké rty hodí k pohybu jejich zkřížených paží, které svědčí o naivně kruté spokojenosti se svými umírajícími oběťmi, jejichž hlavy leží dole."

V Bibli Salome žádá od krále Heroda jako odměnu za svůj svůdný tanec hlavu Jana Křtitele. Klinger zde interpretuje její postavu nově: Zobrazuje ji jako sebevědomou, moderní femme fatale, která přivádí muže do záhuby. Obraz ženy, který byl na přelomu 19. a 20. století populární, protože odpovídal dobovému duchu: Mnoho mužů se v té době cítilo stále více ohroženo stoupajícím sebevědomím a pokračující emancipací žen. Možná dokonce také Georg Treu?

Nové je také, že Klinger Salome barevně napatinoval. Na konci 19. století ještě pořád platilo pravidlo: "Sochy musí být čistě bílé" - nejlépe z bíle se třpytícího mramoru, jako antické sochy. Ale Klinger zná aktuálními výzkumy a ví, že na antických sochách byly objeveny zbytky barev, a proto se chápe štětce: "Nová Salome" je považována za klíčové dílo barevných soch na konci 19. století. A Klinger se odvažuje jít ještě o kousek dál a realizuje něco neslýchaného - kombinuje různé materiály. Všimli jste si, že Salome má překrásné oči z jantaru?

„Na konci 19. století byly Drážďany považovány za centrum umění, které zaspalo nový umělecký vývoj. Dlouho zde vládl vkus první poloviny 19. století: Nazaréni, romantismus. A teprve postupně se mladým umělcům – zejména zde v Drážďanech – podařilo prosadit nové vlivy.“

Tyto nové vlivy, o nichž kurátor Andreas Dehmer mluví, byly velmi rozmanité. Na konci 19. století se prosadila nová generace mladých umělců, jejichž tvorba patřila k novým stylům: impresionismu, symbolismu, secesi. Jejich nové umění vyvolalo velké spory, ale našlo příznivce také v konzervativních Drážďanech. Jeden z ředitelů drážďanských sbírek vzpomíná:

„Občas se tu a tam zablýsklo. A několik mrštných štik, k nimž zejména patřili ředitelé zdejších uměleckých sbírek, v poklidném rybníku s kapry příjemně rozbouřilo vodní hladinu, kterou do té doby nezčeřil ani závan větru. Najednou se vynořila jména, o kterých dosud nikdo neslyšel: Böcklin, Uhde, Liebermann, Thoma, Klinger.“

Ředitelé však o nákupech nemohli rozhodovat svévolně:

„V komisi, která o nákupech rozhodovala, seděl vždy jeden z královských potomků, a také sám král měl své vlastní představy o umění – sice ne vždy tak vyhraněné jako Wilhelm II., který vše, co bylo impresionistické, označoval jako umění ze stoky. V Sasku toto nové umění nebylo přijato až tak zahořkle. Přesto bylo velmi obtížné pokrokové umění prosadit – jako například Maxe Klingera nebo především také Arnolda Böcklina. Debatovalo se částečně i v zemském sněmu, kde se vedly ostré diskuze o tom, co je dobré a co špatné umění.“

Sádrová socha „Nová Salome“ je, jak jsme se už zmiňovali, pouze modelem, podle kterého později Max Klinger vytvořil mramorovou verzi. Ta se dnes nachází v Muzeu výtvarných umění v Lipsku. Restaurátorka Stefanie Exnerová však upozorňuje, že umělec sám sádrový model považoval také za umělecké dílo:

„Pro samotného autora se jedná o zcela samostatné dílo, a jak se o něm sám zmiňuje, jedná se o dílo „s poměrně komplikovanou patinou“. Vlastně můžeme říct, že Klinger u této verze sochy experimentoval s více vrstvami různých barev. Například se pod zelenou barvou Salomenina roucha nachází viditelná červená vrstva barvy. Nebo například pod hnědou barvou vlasů prosvítá u kořínků modrá.“

Klinger barvy pravděpodobně míchal a vyráběl sám. Míchal pigmenty s nejrůznějšími pojidly, jako je olej, vosk nebo klih. To s sebou však již po krátké době přineslo problémy: Některé vrstvy barev spolu k sobě nepřilnuly, a proto dlouho na soše nevydržely. Když byla socha ze sádry roku 1994 restaurována, zjistilo se, že se osmdesát procent celé patiny na obličeji nedochovalo. Na rouše chybí přibližně třicet procent barvy. Cílem restauračních prací bylo chybějící vrstvy barev doplnit a sochu tak přivést, pokud možno do originálního stavu.

„Ale jak tohoto cíle dosáhnout, když nejsou k dispozici žádné přesné údaje ani fotografie? Jako předloha tudíž sloužily ruce, které se zachovaly poměrně dobře. Zbytky stínování očí, obočí nebo také červené barvy rtů měly zůstat viditelné, a proto byly tyto části jen jemně zvýrazněny. Výsledek, jak jej tu dnes vidíte, je sice ucelené barevné umělecké dílo, ale zdání klame.“

Dnes již není možné přesně zrekonstruovat, jak Klinger opravdu tvář Salome namaloval.

- Ort & Datierung

- 1887/88

- Material & Technik

- Gips, bemalt

- Dimenions

- H: 86 cm, B: 53 cm, T: 40 cm

- Museum

- Skulpturensammlung

- Inventarnummer

- ZV 1269