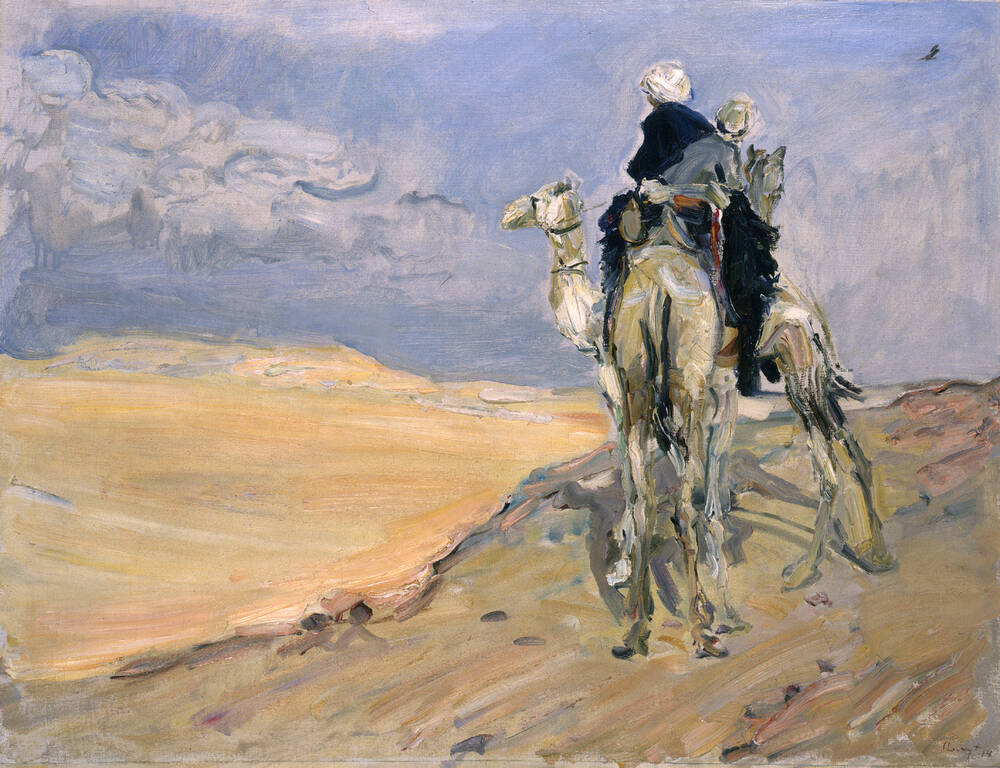

Die beiden Kamelreiter haben die Anhöhe erreicht. Bis zum Horizont erstreckt sich unter ihnen ein Meer aus Sand. Die gleißende Sonne taucht alles in ein grelles Licht. Selbst die Schatten unter den Körpern der Kamele sind hellgrau. Doch Gefahr fesselt den Blick der Reiter und der Tiere: Rasch nähern sich dichte Wolken, ein Sandsturm zieht herauf.

Der Maler Max Slevogt reiste 1914 gemeinsam mit drei Freunden nach Ägypten. Im Gepäck hatte er bereits aufgespannte und grundierte Leinwände in drei Formaten, dazu Farben und Transportkisten. Dieses Gemälde entstand unweit des Simeonklosters bei Assuan am Nil. Wie alle Bilder auf der Reise malte es Slevogt „en plein air“, also unter freiem Himmel. Die Gleichförmigkeit der Wüste hielt er in hellen Ocker- und Gelbtönen fest, mit dünn lasierenden und pastos dick aufgetragenen Partien. Doch erst im Kontrast zu den Kamelreitern, deren schwarzblaue Kleidung er in expressiv gesteigerten Farbflächen wiedergibt, wird der extreme Naturraum charakterisiert. Indem er sie in radikaler Verkürzung in den Vordergrund stellt, hebt er die vegetationslose Weite optisch hervor.

Die ungewöhnlichen Entstehungsumstände notierte Slevogts Begleiter, der Journalist und Kulturwissenschaftler Eduard Fuchs, in seinem Reisetagebuch:

„Wüstenbild gemalt bei stetem und teils starkem Wind. Alles musste ununterbrochen die Staffelei halten …“

Der Wüstenwind hat seine Spuren im Bild hinterlassen: In der Ölfarbe finden sich zahlreiche Sandkörner, die auf die Leinwand geweht wurden.

Auf der fünfwöchigen Reise von Alexandria nach Kairo und von dort den Nil entlang bis in den Süden nach Assuan, vollendete Slevogt 21 Gemälde. Bis auf eines verkaufte er sie alle an die Dresdner Sammlungen, die mit heute noch 17 Gemälden aus der Serie ein einzigartiges Dokument der impressionistischen Landschaftsmalerei besitzen. Mit dem Erlös konnte Slevogt das Gutshaus seiner Schwiegereltern in der Pfalz ersteigern.

Weitere Medien

Seit seiner Kindheit faszinierten Max Slevogt Märchen und Geschichten aus dem Morgenland. Und er war damit nicht allein. In ganz Europa herrschte zu Anfang des 19. Jahrhunderts eine Orientbegeisterung. Kuratorin Heike Biedermann:

„So reiste Slevogt 1914 mit einem Bilderkosmos im Kopf nach Ägypten, der gespeist war von phantastischen Vorstellungen, die er aus Tausendundeiner Nacht kannte und mit denen er sich auch künstlerisch über die Jahre schon beschäftigt hatte, nämlich in vielen, vielen Zeichnungen und Grafiken und Illustrationen, zum Beispiel zu Ali Baba und die Vierzig Räuber und dadurch waren die Sujets auch in seinem Kopf schon vorgegeben, natürlich. Er hatte Ideen, was er in Ägypten finden wollte.“

Und er fand es:

„Das ganze Leben ist tausendundeine Nacht […] so unverfälschter Orient“,

schreibt er begeistert aus Kairo an seine Frau. Doch dieser „unverfälschte“ Orient entspringt seinem europäischen Blick. Und Slevogt blendet so manche Lebensrealität aus. Dennoch romantisiert er seine Motive nicht. Max Slevogt fängt auf impressionistische Weise ein, was er sieht.

The two camel riders have reached the top of the rise. Below them, a sea of sand stretches to the horizon. The blazing sun bathes everything in a harsh light. Even the shadows under the bodies of the camels are bright grey. But the gazes of the riders and their camels are fixed on an imminent danger – the heavy clouds of a sandstorm rapidly approaching.

In 1914, Max Slevogt travelled to Egypt together with three friends. He took with him three sizes of canvases, already primed and stretched on frames, as well as his paints and boxes for transport. Slevogt painted this work not far from the Monastery of Saint Simeon near Aswan on the Nile. Just as for his other paintings on this trip, Slevogt worked plein air – painting out of doors, directly from the landscape. He captured the uniform desert in bright ochre and yellow tones, with some parts in thin glazes, and others in thick pastose layers. But the extreme character of nature first becomes evident in the contrast with the camel riders, their blue-black clothing rendered in areas of colour intensified by the expressive brushstroke. By setting the figures in a radically foreshortened perspective in the foreground, Slevogt highlights this vast expanse, entirely devoid of vegetation.

One of Slevogt’s friends travelling with him was journalist and cultural scholar Eduard Fuchs. In his diary of the journey, Fuchs noted the unusual conditions in which this work was painted:

“Picture of the desert painted in a constant breeze, at times strong. Everyone had to constantly hold on to the easel ...”

The desert wind has left its traces on the work, blowing innumerable tiny grains of sand into the paints. On his five-week trip from Alexandria to Cairo and then up the Nile to Aswan, Slevogt completed 21 paintings. He sold all but one of these to the Dresden art collections. Today, the collections still have 17 works from the series – a unique document of impressionist landscape painting. With the money from the sale, Slevogt was able to buy the Neukastel manor house on his parent-in-laws’ estate in the Palatinate region of Germany.

From childhood on, Max Slevogt had been fascinated by Middle Eastern fables and folk tales – and he was not alone in his enthusiasm. At the start of the nineteenth century, a wave of enthusiasm for “Orientalism” swept Europe. Curator Heike Biedermann:

“So when Slevogt travelled to Egypt in 1914, he already had a world of images fuelled by the fantasies he knew from 1001 Nights and which he’d already explored in his art down the years – namely, in many, many drawings, prints and illustrations, such as those for Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves. As a result, of course, the subjects he was interested in were already fixed in his mind. He had definite ideas about what he wanted to find in Egypt.”

And find it he did. As he enthusiastically wrote to his wife from Cairo:

“All of life here is One Thousand and One Nights […] the authentic Orient.”

But Slevogt’s “authentic Orient” came from his European gaze. He simply disregarded much of the realities of life there. Nonetheless, in his art, rather than romanticising his subject, he applied his Impressionist approach to capture just what he saw.

Obě postavy na velbloudech konečně dospěly na vrchol kopce a nyní se před nimi rozkládá písčitá poušť, která sahá až k samému horizontu. Žhavé slunce noří moře z písku do oslňujícího světla, dokonce i stíny postav jsou světle šedé. Avšak pohled jezdců a velbloudů upoutává jiné nebezpečí: Na obzoru se rychle přibližují husté mraky a s nimi se blíží písečná bouře.

V roce 1914 cestoval Max Slevogt, malíř a autor tohoto obrazu, spolu s dalšími třemi přátely do Egypta. Ve svých zavazadlech s sebou měl už natažená a připravená plátna ve třech formátech, kromě toho navíc také barvy a bedny na přepravu obrazů. Náš obraz vznikl nedaleko Simeonského kláštera u Asuánské přehrady na Nilu. Stejně jako všechny ostatní obrazy maloval Slevogt i tento obraz v plenéru, tedy pod širým nebem. Jednotvárný ráz pouště zachytil ve světlých béžových a žlutých odstínech, které nanášel buď tence nebo velmi tlustě na plátno. Extrémní přírodní podmínky, které v poušti vládnou, Slevogt však zdůrazňuje především pomocí kontrastu pouště a jezdců na velbloudech, jejichž černomodrý oděv znázornil v expresívních barvách. Postavy jsou zobrazeny v radikální zkratce hned v popředí, čímž je opticky zdůrazněna nekonečná krajina bez vegetace.

Obraz vznikl za neobyčejných okolností, jak se o tom ve svém cestovním deníku zmiňuje jeden ze Slevogtových spolucestujících, novinář a kulturní historik Eduar Fuchs:

"Obraz pouště, namalován při neustávajícím a částečně silném větru. Všichni museli bez přestání držet stojan s plátnem ..."

Pouštní vítr zanechal také stopy přímo na obraze: V olejových barvách se nacházejí zrna písku, které na plátno zavál vítr.

Slevogt na své pětitýdenní cestě z Alexandrie do Kaira a odsud podél Nilu až na jih k Asuánu dokončil 21 obrazů. Až na jeden prodal všechny Drážďanským sbírkám, kde se z celé série dodnes nachází ještě 17 děl jako jedinečný dokument impresionistického krajinného malířství. Za obnos, který mu prodej obrazů přinesl, Slevogt mohl v dražbě koupit statek svého tchána a tchýně ve Falci.

Maxe Slevogta od dětství fascinovaly pohádky a příběhy z Orientu. A nebyl sám. Na počátku 19. století propadla celá Evropa nadšení pro Orient. Kurátorka Heike Biedermannová:

„Slevogt se tedy roku 1914 vydal na cestu do Egypta s nejrůznějšími fantastickými představami, jež měly původ v četbě pohádek Tisíce a jedné noci. Slevogt se jimi umělecky zabýval již v letech před svou cestou, a to v nečetných kresbách, grafikách a ilustracích, jako například k vyprávění o Ali Babovi a čtyřiceti loupežnících. Náměty měl tudíž tedy v hlavě předem. Měl představu, co chce v Egyptě najít.“

A to také našel:

„Celý život je tisíc a jedna noc [...] tedy nezfalšovaný Orient.“

píše nadšeně z Káhiry své ženě. Tento „nezfalšovaný“ Orient je však podmíněn jeho evropským pohledem. Slevogt ignoruje části reality, přesto však své motivy neromantizuje. Zachycuje impresionistickým stylem to, co vidí.

- Ort & Datierung

- 1914

- Material & Technik

- Öl auf Leinwand

- Dimenions

- 73,5 x 95,5 cm (Katalogmaß 2010) 104 x 126 x 9 cm (Rahmenmaß, Tobias Lange, 10.05.2010)

- Museum

- Galerie Neue Meister

- Inventarnummer

- Gal.-Nr. 2547