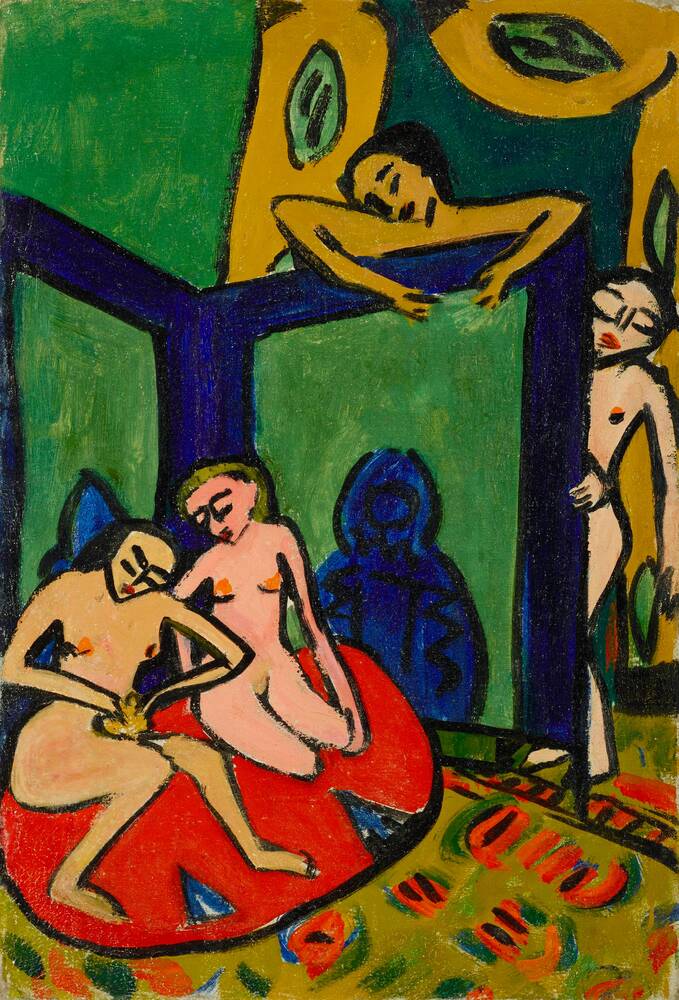

Kaum 3 Kilometer von hier entfernt, in der Dresdner Friedrichstadt, hat Erich Heckel 1911 dieses Bild gemalt. Sein Freund und Künstlerkollege Ernst Ludwig Kirchner hatte dort einen leerstehenden Schusterladen gemietet. Der Raum wurde ausstaffiert mit einem großen, leuchtend grünen Wandschirm, den die Maler mit einer Bordüre und einer hockenden Figur in tiefem Blau bemalten. An die Wand hängten sie einen gelben Vorhang, den sie mit grünen Medaillons verzierten. In jeder freien Stunde trafen sich die Künstler hier zum Zeichnen und zum Malen. Dabei waren oft junge Mädchen aus proletarischem Milieu, die die Künstler dafür bezahlten, nackt Modell zu stehen. Die Minderjährigkeit war für die Künstler damals kein Problem, heute ist unsere Sichtweise eine andere. Sie sahen das jugendliche Alter der Modelle als Garant für ungezwungene, natürliche Motive.

Zu dem Freundeskreis gehörten neben Heckel und Kirchner auch noch Max Pechstein und Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. Letzterer hatte sechs Jahre zuvor, im Sommer 1905, die Idee, sich als Künstlergruppe „Brücke“ zu nennen. Der Name sollte Ausdruck der Zusammenarbeit und des gemeinsamen Aufbruchs zu neuen Ufern sein.

Und in der Tat betraten die Maler künstlerisches Neuland. Die starken Farben, unvermischt und flächig nebeneinander gesetzt, der Verzicht auf Perspektive, und nicht zuletzt die freizügigen Motive – dies alles schockierte die bürgerliche Welt des späten Kaiserreichs. Erst später erkannte man, wie sehr diese vermeintliche Anti-Kunst von tiefer Liebe zur Malerei und auch von großem handwerklichen Können getragen war. Wie es Heckel beispielsweise gelingt, der hinter dem Wandschirm vorlugenden Franziska Fehrmann, genannt Fränzi, mit wenigen schnellen Strichen momenthaftes Leben einzuhauchen, zeugt von großer Meisterschaft.

Weitere Medien

Nicht nur in ihren Werken zeigten die Brücke-Künstler eine große Begeisterung für das in ihren Augen vermeintlich "Ursprüngliche". Sie statteten auch ihre Ateliers auf ungewöhnliche Weise aus: mit Bildern, bemalten Vorhängen und selbstgefertigten Möbeln. Hierfür ahmten sie die Kunst afrikanischer Regionen oder pazifischer Inseln nach und eigneten sich im weitesten Sinne deren Ästhetik an.

Anregungen fanden sie zum Beispiel im Dresdner Museum für Völkerkunde. Vor allem Ernst Ludwig Kirchner war dort häufig mit Stift und Skizzenbuch anzutreffen. Zeichnend erkundete er die für ihn ungewöhnlichen Formen und das Wesen der Arbeiten. Die Brücke-Künstler sahen die Objekte als Zeugnisse einer, wie sie es formulierten, „unverfälschten“ Kunst – im Gegensatz zu der vermeintlich von der Zivilisation „verdorbenen“ europäischen Kunst. Die Frage, WIE die Objekte ins Museum gelangt waren, stellten sie sich offenbar nicht. Tatsächlich verdankten Völkerkundemuseen viele ihrer Objekte der oft brutalen Ausübung kolonialer Herrschaft.

Eine andere Inspirationsquelle waren die „Völkerschauen“, die in Dresden im Schnitt zweimal im Jahr stattfanden. Für dieses einträgliche Unterhaltungsgeschäft wurden Menschen aus Afrika, Asien, Ozeanien oder Nordamerika im Zoologischen Garten auf der „Völkerwiese zur Schau gestellt, in nachgebauten Behausungen, manchmal in ganzen Dörfern. Vor einem Massenpublikum demonstrierten sie Riten und Bräuche, führten Tänze auf oder zeigten Handwerkstechniken. Nachdem Kirchner und Heckel 1910 die „Samoa-Schau“ gesehen hatten, schufen sie wenig später Grafiken, die Samoanerinnen zeigten. Was sie von dem Spektakel ansonsten hielten, wissen wir nicht. Zweifelsohne bestätigten die Völkerschauen Vorurteile und Klischees des Kolonialismus. Die Inszenierungen behaupteten die Andersartigkeit der angeblich „naturnahen“ Kulturen und bekräftigten die vermeintliche Überlegenheit Europas.

In 1911, artist Erich Heckel painted this work in Dresden’s Friedrichstadt district, hardly three kilometres from here. There, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, his friend and fellow artist, had rented an empty shoemaker’s shop. The room was equipped with a large folding screen in bright green, which the artists painted with a border and a squatting female figure in dark blue. On the wall, they hung a yellow curtain which they decorated with green medallions. Whenever they had time free, the artists met here to draw and paint. They often paid young working-class girls to join them and model nude for their life drawings. At that time, these artists did not worry about many of their models being under-age – a concern we view very differently today. For them, the youth of their models was a guarantee of natural, unconstrained motifs.

Along with Heckel and Kirchner, this circle of friends also included Max Pechstein and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. In summer 1905, six years before this work was painted, Schmidt-Rottluff had the idea of calling their artists’ group Die Brücke. The name Brücke – meaning ‘bridge’ – was intended to express the group’s collaborative approach as well as their joint artistic departure to new worlds.

And in fact, the Brücke artists did break fresh ground. The middle-class world of late imperial German was shocked by their powerful colours, applied unmixed and juxtaposed as flat surfaces, the renunciation of linear perspective, and not least the free-spirited, explicit subjects. Only later did mainstream society realise just how much this so-called ‘anti-art’ was motivated by a profound love of painting and executed with exceptional artistic skill. This work, for example, shows Heckel’s mastery only too clearly in how he captures, in just a few swift lines, such a lively snapshot of Franziska Fehrmann, nicknamed Fränzi, as she peers around the screen.

The Brücke artists were very enthusiast about what they considered the “unspoilt” and “natural”. That enthusiasm not only evident their works, but also in how they decorated their studios – an idiosyncratic mix of pictures, painted curtains and furniture they had carved or made themselves. They modelled their designs on the art of African regions or the Pacific islands and, in the broadest sense, appropriated those aesthetics as well.

They took their inspiration from, for instance, the exhibits in Dresden’s Ethnological Museum. Above all, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner could often be found there with his sketch book and pencil. Through his drawings, he explored the essence of these works, and their formal idioms, for him so novel and unfamiliar. The Brücke artists regarded these artefacts as testifying to – in their terms – a natural, “authentic” art, the quintessential opposite of traditional European art allegedly “corrupted” by civilisation. Evidently, they did not ask HOW these objects entered the museum’s collection. In fact, anthropological museums often obtained many of their exhibits through the brutal exploitation of colonial rule.

The Brücke artists found another source of inspiration in what were called “ethnological expositions”. On average, such “human zoos” were presented twice a year in Dresden. On an open space in the Zoological Gardens, these popular and profitable “expositions” displayed people from Africa, Asia, Oceania or North America in replica dwellings, sometimes even in entire villages. In front of the crowds, they had to act out rituals and customs, perform dances, or demonstrate craft techniques. Soon after Kirchner and Heckel saw the “Samoa exposition” in 1910, they were producing prints of Samoan people – but have left no record of what they otherwise thought of this spectacle. Undoubtedly, the “human zoos” confirmed the prejudices and clichés of colonialism. The staged shows asserted the Otherness of these cultures, allegedly living “close to nature”, and further strengthened the idea of Europe’s purported superiority.

Zdejší obraz vznikl necelé tři kilometry odsud, v drážďanském Friedrichstadtu, kde jej namaloval roku 1911 Erich Heckel. Jeho přítel a umělecký kolega Ernst Ludwig Kirchner tam měl najmutou bývalou a nyní prázdnou ševcovskou dílnu. Do místnosti postavili velký, svítivě zelený paraván, na který oba umělci namalovali barevný lem a sedící tmavě modrou postavu. Na zeď pověsili žlutý závěs, který ozdobili zelenými medailonky. Zde se oba přátelé scházeli každou volnou minutu a společně zde kreslili a malovali. Často je sem doprovázely mladé dívky z protelářského prostředí, kterým malíři platili za to, že jim nahé stály modelem. To, že dívky byly ještě nezletilé, tenkrát nebylo žádným problémem, naopak jejich mladost a nezletilost pro ně byla zárukou nenucenosti a přirozenosti. Dnes bychom to samozřejmě viděli jistě trochu jinak.

K okruhu přátel patřili kromě Heckela a Kirchnera také ještě Max Pechstein a Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. Ten měl šest let před tím - v létě roku 1905 - nápad, uměleckou skupinu pojmenovat "Brücke", česky "Most". Umělce spojovalo hledání nového uměleckého vyjádření, které mělo směřovat do budoucnosti a tvořit tak most mezi současností a minulostí.

A opravdu se jim podařilo najít nový umělecký styl. Silné, expresívní barvy, nanášené na plátno vedle sebe v plochách bez přechodů, zřeknutí se perspektivy a v neposlední řadě sexuálně svobodomyslné motivy - to vše šokovalo měšťanský svět německé císařské říše. Teprve později svět pochopil, jak hluboká láska a vášeň k malířství a jak zkušené řemeslné zpracování se za tímto tzv. "anti-uměním" skrývaly. Důkazem toho je také zdejší obraz. Všimněte si, jak pár jednoduchými, rychlými tahy štětcem se Heckelovi podařilo vdechnout život a výraz Franzisce Fehrmannové, zvané Fränzi, která právě vykukuje zpoza paravanu. To svědčí o velkém malířském mistrovství.

Umělci skupiny „Brücke“ – česky „Most“ – vyjadřovali své velké nadšení pro vše, co považovali za tzv. „původní“. Nejen jejich díla, ale také zařízení jejich ateliérů odpovídalo tomuto uměleckému přesvědčení: obrazy na stěnách, malované závěsy a nábytek, který vlastnoručně vyrobili. Přitom napodobovali africké umění či umění z tichomořských ostrovů a přejímali v nejširším slova smyslu jejich estetiku.

Inspiraci našli například v drážďanském Etnologickém muzeu. Zejména Ludwiga Kirchnera bylo možné v muzeu často zahlédnout s tužkou a blokem na kreslení. Studoval tak pro něj neobvyklé formy a podstatu těchto děl. Umělci skupiny „Brücke“ považovali vystavené objekty za důkaz tzv. „nezkaženého“ umění – na rozdíl od evropského umění, které bylo podle jejich názoru „zkažené“ moderní civilizací. Otázku, JAK se předměty do muzea dostaly, si očividně nekladli. Dnes víme, že etnologická muzea za mnoho svých výstavních objektů často vděčí brutální nadvládě koloniálních velmocí.

Dalším zdrojem inspirace byly „výstavy národů“, které se v Drážďanech konaly průměrně dvakrát do roka a při nichž byli v zoologické zahradě na tzv. „louce národů“ vystavováni lidé z Afriky, Asie, Oceánie nebo Severní Ameriky – a sice v replikách původních obydlí a někdy dokonce také celých vesnic. Před masou diváků museli předvádět typické zvyky a obyčeje, tradiční tance a řemeslné dovednosti. Tento zábavní obchod s původními obyvateli byl tehdy velmi výnosný.

Kirchner a Hackel roku 1910 sami navštívili a shlédli výstavu obyvatel Samoy. O něco později pak vytvořili grafiky zobrazující samojské ženy. Co si o této podívané mysleli jinak, nám není známo. V každém případě tyto etnologické „výstavy“ potvrzovaly bezpochyby předsudky a klišé, které vládly v koloniálních zemích. Tyto inscenace stavěly do popředí odlišnost tak zvaných „přírodních“ národů a měly být důkazem údajné evropské nadřazenosti.

- Ort & Datierung

- 1911

- Material & Technik

- Vorderseitig: Öl auf Leinwand, Rückseitig: Tempera auf Leinwand

- Dimenions

- 75 x 53,4 cm

- Museum

- Galerie Neue Meister

- Inventarnummer

- Inv.-Nr. 2016/07