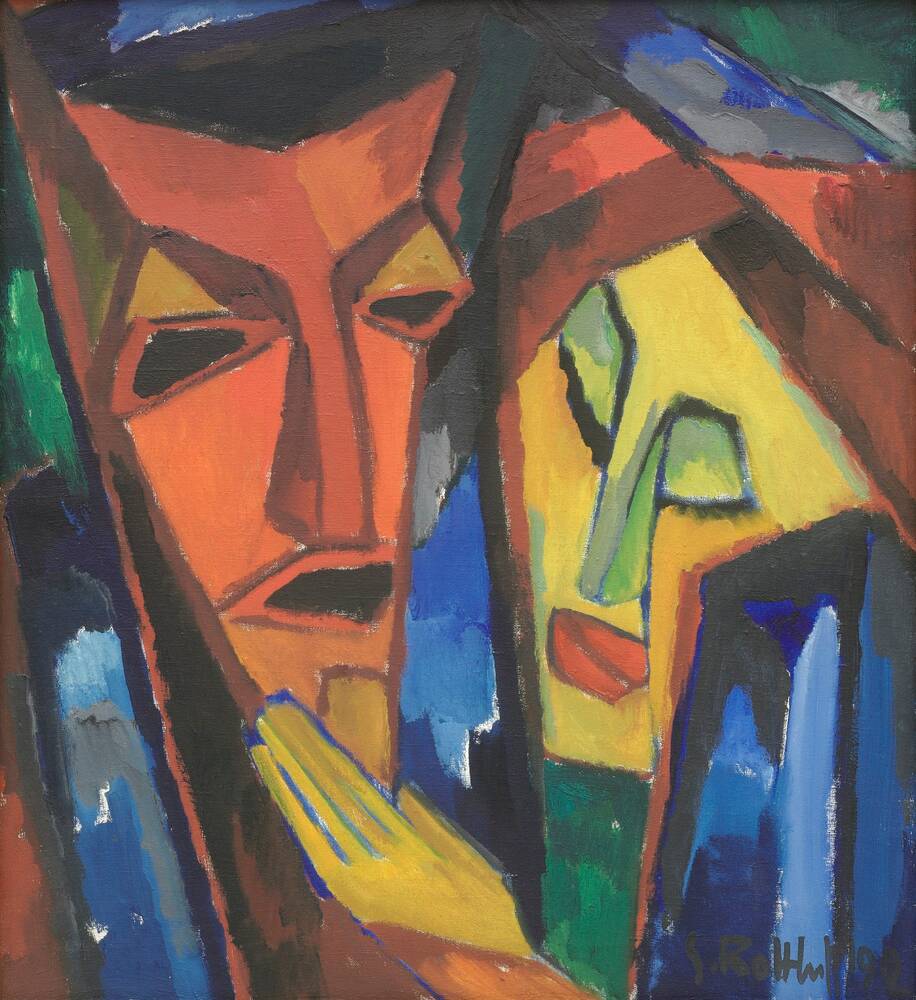

Der Titel des Bildes „Frauenkopf mit Maske“, das Karl Schmidt-Rottluff 1912 in Berlin malte, verspricht eine Eindeutigkeit, die das Bild nicht besitzt. Zu dessen rätselhaftem Charakter sagt die Kuratorin Birgit Dalbajewa:

„Interessant ist, dass man gar nicht entscheiden kann letzten Endes: Ist es wirklich eine Maske, die die Frau in der Hand hält, oder ist es ein Gegenüber von einem Mann und einer Frau, weil das Gesicht der Frau, ist genauso vereinfacht dargestellt, es ist ebenfalls auf wenige Grundformen runtergebrochen, auf eine Nase, die wie geschnitzt erscheint, auf sehr einfache Augenhöhlen mit den geschlossenen Augen, und insofern schafft er in so ganz stark reduzierten, kubistisch-prismatisch gebrochenen Farbfeldern ein vis-à-vis von Mann und Frau, einen ganz reduzierten Dialog, sie schließt die Augen, die Maske hat ja eh keinen direkten Blick, und diese Auseinandersetzung zwischen den Geschlechtern, das war ja auf jeden Fall etwas, was in der Zeit interessiert hat, was die Künstler sehr interessiert hat, und so hat das Bild, ohne dass es zu vordergründig ist, ganz verschiedene Interpretationsebenen.“

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff begeisterte sich in jener Zeit für afrikanische Masken, deren schroffe Abstraktion ihn faszinierte, und für den französischen Kubismus, den er auf der „Sonderbund“-Ausstellung in Köln im selben Jahr kennengelernt hatte. Pablo Picasso und Georges Braque beeindruckten ihn mit ihrer multiperspektivischen Sicht auf ein und denselben Gegenstand. Hinzu kommen die starken Farben, die für die Maler der „Brücke“ typisch waren: Gelb trifft auf Blau auf Grün und Rot. All diese Elemente verarbeitet Schmidt-Rottluff zu seiner Darstellung von Frau und Mann – oder Frau und Maske? – in zärtlicher Symbiose.

Weitere Medien

Dresden, 1905. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff und Erich Heckel sind Studenten an der Technischen Hochschule. Ihr Fach: Architektur. Eigentlich interessiert sie jedoch die Kunst. Nicht die akademische Kunst nach vorgegebenen Theorien. Ihnen schwebt eine neue Kunst vor, ohne Regeln, die spontan aus dem Augenblick heraus entstehen soll, im Atelier, das zugleich auch als Wohnraum dient. Kunst und Leben sollen eins sein. Um ihr Projekt zu verwirklichen, gründen die vier eine Künstlergruppe: "Die Brücke":

"Als Jugend, die die Zukunft trägt, wollen wir uns Arm- und Lebensfreiheit verschaffen gegenüber den wohlangesessenen älteren Kräften. Jeder gehört zu uns, der unmittelbar und unverfälscht wiedergibt, was ihn zum Schaffen drängt."

Für junge Künstler war es nicht leicht, sich in der Kunstszene zu etablieren – als Gruppe war das einfacher. Bereits im ersten halben Jahr produzieren die vier genügend Bilder für eine Ausstellung in Dresden – in einem Lampengeschäft. In den folgenden Jahren zeigen sie ihre Werke sowohl in renommierten Dresdner Galerien als auch in Wanderausstellungen, die durch ganz Deutschland geschickt werden – in Kunstvereinen und Galerien. Dort ist man generell von Neuem angetan, konservative Kritiker aber schreiben abwertend von "Farbenirrsinn" und "Höllenkarneval".

Auch Werbung macht die Gruppe gemeinsam, mit selbst entworfenen Plakaten, Katalogen und Einladungskarten. Gegen einen Jahresbeitrag bietet sie passive Mitgliedschaften an, verbunden mit eigens gestalteten Mitgliedskarten und Jahresmappen. Auf diese Weise schafft sich die "Brücke" ein Netzwerk aus Förderern und Sammlern.

1906 tritt Max Pechstein der Gruppe bei, Fritz Bleyl verlässt sie 1907. Bis Ende 1911 ziehen alle Mitglieder von Dresden nach Berlin. Dort kommt es zu Konflikten. 1913 löst sich die "Brücke" nach acht Jahren auf.

Nicht nur in ihren Werken zeigten die Brücke-Künstler eine große Begeisterung für das in ihren Augen vermeintlich "Ursprüngliche". Sie statteten auch ihre Ateliers auf ungewöhnliche Weise aus: mit Bildern, bemalten Vorhängen und selbstgefertigten Möbeln. Hierfür ahmten sie die Kunst afrikanischer Regionen oder pazifischer Inseln nach und eigneten sich im weitesten Sinne deren Ästhetik an.

Anregungen fanden sie zum Beispiel im Dresdner Museum für Völkerkunde. Vor allem Ernst Ludwig Kirchner war dort häufig mit Stift und Skizzenbuch anzutreffen. Zeichnend erkundete er die für ihn ungewöhnlichen Formen und das Wesen der Arbeiten. Die Brücke-Künstler sahen die Objekte als Zeugnisse einer, wie sie es formulierten, „unverfälschten“ Kunst – im Gegensatz zu der vermeintlich von der Zivilisation „verdorbenen“ europäischen Kunst. Die Frage, WIE die Objekte ins Museum gelangt waren, stellten sie sich offenbar nicht. Tatsächlich verdankten Völkerkundemuseen viele ihrer Objekte der oft brutalen Ausübung kolonialer Herrschaft.

Eine andere Inspirationsquelle waren die „Völkerschauen“, die in Dresden im Schnitt zweimal im Jahr stattfanden. Für dieses einträgliche Unterhaltungsgeschäft wurden Menschen aus Afrika, Asien, Ozeanien oder Nordamerika im Zoologischen Garten auf der „Völkerwiese zur Schau gestellt, in nachgebauten Behausungen, manchmal in ganzen Dörfern. Vor einem Massenpublikum demonstrierten sie Riten und Bräuche, führten Tänze auf oder zeigten Handwerkstechniken. Nachdem Kirchner und Heckel 1910 die „Samoa-Schau“ gesehen hatten, schufen sie wenig später Grafiken, die Samoanerinnen zeigten. Was sie von dem Spektakel ansonsten hielten, wissen wir nicht. Zweifelsohne bestätigten die Völkerschauen Vorurteile und Klischees des Kolonialismus. Die Inszenierungen behaupteten die Andersartigkeit der angeblich „naturnahen“ Kulturen und bekräftigten die vermeintliche Überlegenheit Europas.

From its title Woman’s Head and Mask, this work, painted by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff in Berlin in 1912, promises an explicitness the composition seems to lack. Let’s hear curator Birgit Dalbajewa on the rather mysterious nature of this work:

“Interestingly, in the final analysis, you can’t actually decide what you see. Is the woman really holding a mask in her hand? Or is it a man’s and woman’s face juxtaposed – after all, the forms of the woman’s face are just as simplified. It is also broken down into a few basic shapes – a nose looking as if it were carved, and remarkably simple eye sockets with the eyes closed. In that sense, through this radically reduced, broken cubist and prismatic fields of colour, Schmidt-Rottluff juxtaposes a man and woman, creating a very condensed dialogue – her eyes are closed, and the mask has, in any case, no direct gaze. And this critical exploration of relationships between men and women was a topic of great interest in those years – and something artists were also very interested in. So, without making too much of it, this work offers vastly different levels of interpretation.”

At that time, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff was fascinated by the rough abstraction of African masks. He was also influenced by French Cubism, which he had first seen in the Sonderbund exhibition in Cologne the same year he painted this work. He was impressed by the multiple perspectives of one and the same object in works by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. In addition, Schmitt-Rottluff's art included the strong pure colours so characteristic of works by the Brücke group of artists. Here, yellow is juxtaposed with blue, green and red. In a gentle symbiosis, Schmidt-Rottluff fuses all these elements into a depiction of a woman and a man – or a woman and a mask?

Dresden, 1905. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Erich Heckel were all at the city’s Royal Saxon Polytechnic Institute studying architecture. But their real interest lay in the visual arts. Rather than following academic art based on fixed theories, they envisaged a new art without rules. Their art would emerge spontaneously from the immediate moment in the studio – a space which also served as a place to live. In this vision, life and art ought to be one – and to realise their project, these four students founded an artists’ group which they called “Die Brücke” – “The Bridge”:

“...as youth that is carrying the future, we intend to obtain freedom of movement and of life for ourselves in opposition to older, well-established powers. Whoever renders directly and authentically that which impels him to create is one of us…”

Young artists found it hard to gain a foothold in the art scene – and as a group, that was easier. After just six months, these four aspiring artists already had enough pictures to hold a first exhibition in Dresden – in a lamp shop. Over the following years, they not only presented their works in renowned galleries in Dresden, but also in temporary exhibitions shown in galleries and art associations across Germany. In general, the audiences in these locations appreciated this new art, though conservative critics disparagingly called it a “madness of colour” and a “carnival of hell”.

The group organised their own advertising, designing posters, catalogues and invitations themselves. The Brücke artists’ group also offered passive membership against an annual fee. Passive members received a personal membership card designed by one of the artists and annual portfolios. In this way, the Brücke created a network of supporters and collectors.

There were also some changes in the members, with Max Pechstein joining in 1906 and Fritz Bleyl leaving one year later in 1907. By the end of 1911, all the Brücke members had moved from Dresden to Berlin. There, the group became looser and various conflicts emerged between the members. Ultimately, in 1913, after eight years, the Brücke group disbanded.

The Brücke artists were very enthusiast about what they considered the “unspoilt” and “natural”. That enthusiasm not only evident their works, but also in how they decorated their studios – an idiosyncratic mix of pictures, painted curtains and furniture they had carved or made themselves. They modelled their designs on the art of African regions or the Pacific islands and, in the broadest sense, appropriated those aesthetics as well.

They took their inspiration from, for instance, the exhibits in Dresden’s Ethnological Museum. Above all, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner could often be found there with his sketch book and pencil. Through his drawings, he explored the essence of these works, and their formal idioms, for him so novel and unfamiliar. The Brücke artists regarded these artefacts as testifying to – in their terms – a natural, “authentic” art, the quintessential opposite of traditional European art allegedly “corrupted” by civilisation. Evidently, they did not ask HOW these objects entered the museum’s collection. In fact, anthropological museums often obtained many of their exhibits through the brutal exploitation of colonial rule.

The Brücke artists found another source of inspiration in what were called “ethnological expositions”. On average, such “human zoos” were presented twice a year in Dresden. On an open space in the Zoological Gardens, these popular and profitable “expositions” displayed people from Africa, Asia, Oceania or North America in replica dwellings, sometimes even in entire villages. In front of the crowds, they had to act out rituals and customs, perform dances, or demonstrate craft techniques. Soon after Kirchner and Heckel saw the “Samoa exposition” in 1910, they were producing prints of Samoan people – but have left no record of what they otherwise thought of this spectacle. Undoubtedly, the “human zoos” confirmed the prejudices and clichés of colonialism. The staged shows asserted the Otherness of these cultures, allegedly living “close to nature”, and further strengthened the idea of Europe’s purported superiority.

Název obrazu "Hlava ženy s maskou" vyvolává na první pohled dojem, že motiv obrazu je jednoznačný, při přesnějším pohledu však zjistíme, že tomu tak není. Jedná se o dílo Karla Schmidta-Rottluffa, které namaloval roku 1912 v Berlíně. Záhadný charakter obrazu popisuje kurátorka Birgit Dalbajewa:

"Zajímavé je, že nakonec vlastně nemůžeme přesně říci: Je to opravdu maska, kterou žena drží v ruce, nebo se jedná spíše o druhou osobu, muže či ženu. Obličej ženy je totiž, stejně jako domnělá maska, zobrazen velmi schematicky a zjednodušeně a je omezen pouze na několik základních tvarů, a sice na nos, který vypadá, jako by byl vyřezán, a na velmi zjednodušené oční důlky se zavřenými víčky. Tímto způsobem - tedy pomocí velmi redukovaných kubisticky-působících barevných ploch - se umělci podařilo zobrazit vis-á-vis muže a ženu, jejich dialog, během něhož má ona zavřené oči a maska se naopak nemůže dívat nikam. A právě tento střet obou pohlaví stál v každém případě v centru tehdejšího zájmu, o co se umělci velmi zajímali. Obraz nám tudíž nabízí velmi různé možnosti interpretace, aniž by se jednotlivé významy draly do popředí.

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff byl v té době nadšen africkými maskami, jejichž strohá abstrakce ho fascinovala, a francouzským kubismem, se kterým se seznámil na výstavě umělecké skupiny "Sonderbund" v Kolíně roku 1912. Zde ho zaujaly obrazy Pabla Picassa a Georges Braqua, na nichž byly předměty zobrazeny z více úhlů současně a rozloženy na jednoduché geometrické tvary. Schmidt-Rottluff na svém obrazu navíc používá sytých barev, které jsou typické pro malíře skupiny "Brücke": Žlutá se tu střetá s modrou a zelená s červenou. Všechny tyto prvky jsou tu symbioticky spojeny v něžném zobrazení ženy a muže - či ženy a masky?

Drážďany, roku 1905. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff a Erich Heckel studují právě na Technické univerzitě. A sice obor architektury. Ve skutečnosti se však zajímají o umění. Ne o akademické umění podle předem daných teorií. Představují si nový druh umění, bez pravidel, které by vznikalo ze spontánního okamžiku, v ateliéru, který by zároveň sloužil jako obytná místnost. Umění a život mají tvořit jednotu. A aby mohli svůj projekt zrealizovat, založila čtveřice umělců skupinu Die Brücke – česky Most:

„My mladí, kteří neseme budoucnost, se chceme osvobodit od chudoby a získat svobodu oproti starším, majetným vrstvám. Patří k nám každý, kdo se přímo a nezkresleně snaží vyjádřit to, co ho nutí tvořit.“

Pro mladé umělce nebylo snadné prosadit se na umělecké scéně – ale jako skupina to bylo o něco snazší. Již během prvního půl roku tito čtyři umělci vytvořili dostatek obrazů pro vlastní výstavu v Drážďanech, která se konala v obchodě s lampami. V následujících letech pak vystavují svá díla v renomovaných drážďanských galeriích stejně jako na putovních výstavách, které se konají po celém Německu – v uměleckých spolcích a galeriích. Publikum je novým uměním nadšeno, ale konzervativní kritici píšou pejorativně o „barevném šílenství“ a „pekelném karnevalu“.

Skupina také vydává pro své výstavy vlastnoručně navržené plakáty, katalogy a pozvánky. Za roční poplatek nabízí pasivní členství, spojené se speciálně navrženými členskými průkazy a ročenskými sborníky. Tímto způsobem si skupina Brücke vytvořila celou síť mecenášů a sběratelů.

Roku 1906 se ke skupině připojil Max Pechstein a roku 1907 ji naopak Fritz Bleyl opustil. Do konce roku 1911 se všichni členové přestěhovali z Drážďan do Berlína, kde však došlo k neshodám, a roku 1913 se skupina Brücke po osmi letech rozpadla.

Umělci skupiny „Brücke“ – česky „Most“ – vyjadřovali své velké nadšení pro vše, co považovali za tzv. „původní“. Nejen jejich díla, ale také zařízení jejich ateliérů odpovídalo tomuto uměleckému přesvědčení: obrazy na stěnách, malované závěsy a nábytek, který vlastnoručně vyrobili. Přitom napodobovali africké umění či umění z tichomořských ostrovů a přejímali v nejširším slova smyslu jejich estetiku.

Inspiraci našli například v drážďanském Etnologickém muzeu. Zejména Ludwiga Kirchnera bylo možné v muzeu často zahlédnout s tužkou a blokem na kreslení. Studoval tak pro něj neobvyklé formy a podstatu těchto děl. Umělci skupiny „Brücke“ považovali vystavené objekty za důkaz tzv. „nezkaženého“ umění – na rozdíl od evropského umění, které bylo podle jejich názoru „zkažené“ moderní civilizací. Otázku, JAK se předměty do muzea dostaly, si očividně nekladli. Dnes víme, že etnologická muzea za mnoho svých výstavních objektů často vděčí brutální nadvládě koloniálních velmocí.

Dalším zdrojem inspirace byly „výstavy národů“, které se v Drážďanech konaly průměrně dvakrát do roka a při nichž byli v zoologické zahradě na tzv. „louce národů“ vystavováni lidé z Afriky, Asie, Oceánie nebo Severní Ameriky – a sice v replikách původních obydlí a někdy dokonce také celých vesnic. Před masou diváků museli předvádět typické zvyky a obyčeje, tradiční tance a řemeslné dovednosti. Tento zábavní obchod s původními obyvateli byl tehdy velmi výnosný.

Kirchner a Hackel roku 1910 sami navštívili a shlédli výstavu obyvatel Samoy. O něco později pak vytvořili grafiky zobrazující samojské ženy. Co si o této podívané mysleli jinak, nám není známo. V každém případě tyto etnologické „výstavy“ potvrzovaly bezpochyby předsudky a klišé, které vládly v koloniálních zemích. Tyto inscenace stavěly do popředí odlišnost tak zvaných „přírodních“ národů a měly být důkazem údajné evropské nadřazenosti.

- Ort & Datierung

- 1912

- Material & Technik

- Öl auf Leinwand

- Dimenions

- 84,5 x 76,5 cm (Katalogmaß 2010) 84 x 76 cm (Katalogmaß 1987) 84,7 x 76,3 cm (Inventurmaß, 23.04.2010) 99,3 x 91,4 x 4 cm (Rahmenmaß, Tobias Lange, 23.04.2010)

- Museum

- Galerie Neue Meister

- Inventarnummer

- Gal.-Nr. 3925