"Kinder sind für Kokoschka etwas ganz Besonderes. Sie sind wertvoll, sie sind Erlebnisträger, sie erleben besonders intensiv –"

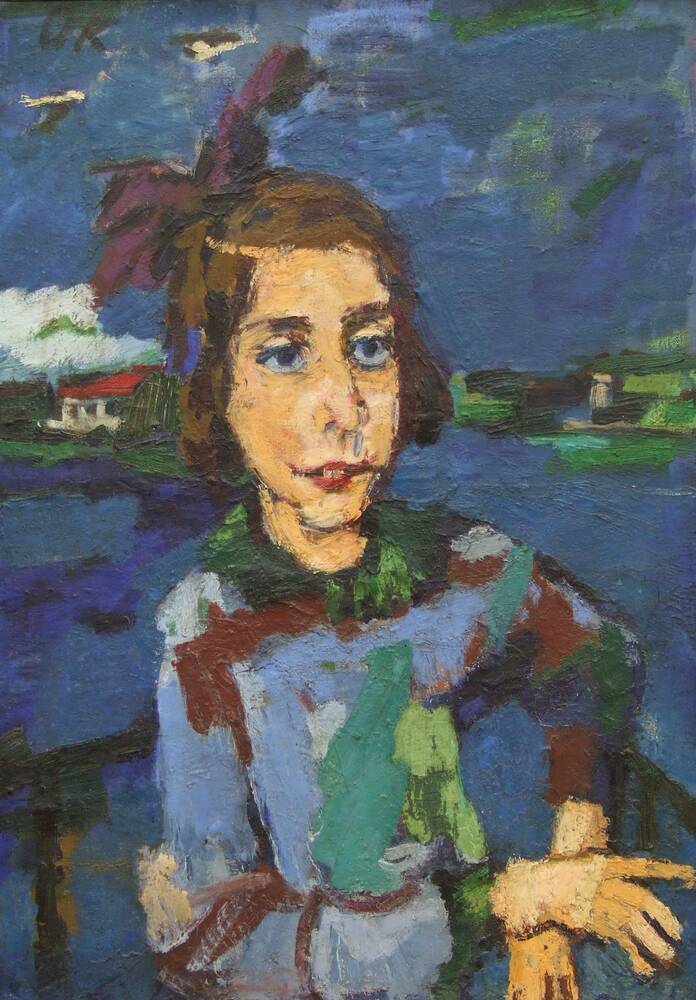

1921 porträtiert Oskar Kokoschka Gitta Wallerstein, die Tochter eines befreundeten Kunsthändlers. Kokoschka ist damals mit 35 Jahren jüngster Professor an der Dresdner Kunstakademie; seine wilde Zeit als Enfant terrible der Wiener Kunstszene hat er hinter sich. Die Porträts, die er jetzt malt, sind beinahe Psychogramme. Dieses hier spiegelt die ernste, schüchterne Aufmerksamkeit der Heranwachsenden. Kokoschka malt sie in leuchtenden Blau- und Grüntönen vor einer weiten Flusslandschaft. Die Kuratorin Birgit Dalbajewa erzählt:

"Gitta Wallerstein war zehn Jahre alt, als sie im Atelier von Professor Kokoschka in der Kunstakademie an der Brühlschen Terrasse neben dem Albertinum Modell saß. Sie erinnert sich, dass sie wahnsinnig aufgeregt war: dieser Mann mit dem Wiener Akzent. Sie durfte ihre Turnübungen im Atelier vollführen, sie durfte sich also frei bewegen, und manchmal nahm der Maler eine Farbtube, kam an ihr Kleid und fragte sie ganz ernsthaft nach ihrer Meinung, ob sie meine, dass dieser Ton passe."

Gitta Wallerstein nahm schon damals Tanzunterricht, später wurde sie Solotänzerin an der Berliner Staatsoper. Weil sie jüdischer Herkunft war, verlor sie während des Nationalsozialismus ihre Stellung. 1939 emigrierte sie in die USA. Dort trat sie anfangs noch als Tänzerin auf; später arbeitete sie als Arzthelferin und Röntgenassistentin. Bis zu ihrem Tod 2008 engagierte sie sich für die Menschenrechte und betreute Aids-Kranke. Mit Oskar Kokoschka verband sie eine lebenslange Freundschaft.

Weitere Medien

Bis zum Ende des Ersten Weltkriegs umfasst die moderne Sammlung der Dresdener Gemäldegalerie zwar Werke des Realismus, Symbolismus usw., aber so gut wie keine Gemälde der neuesten, aktuellen Kunstrichtungen: keinen Gauguin, keinen van Gogh, nur einige wenige Expressionisten. Noch ist der Direktor Hans Posse machtlos gegenüber der konservativen Erwerbungspolitik der Ankaufskommission aus honorigen Kunstprofessoren und dem sächsischen Kronprinzen.

Das ändert sich 1919. In den Dresdener Feuilletons wird eine „Verjüngung“ der Galerie gefordert. Posse setzt durch, dass die Ankaufskommission durch einen fortschrittlich gesinnten Galeriebeirat ersetzt wird. Trotz finanzieller Nöte baut er nach und nach eine Sammlung der Moderne auf, angefangen mit Werken von Kokoschka, Heckel und Pechstein. Posse prägt den Begriff der „Modernen Galerie“. Vor allem ab 1925 kann er Hauptwerke von Munch, Kokoschka, Beckmann und vielen anderen erwerben, die zunächst auch im Semperbau am Zwinger gezeigt werden. Das bürgerliche Engagement eines Freundeskreises, des "Patronatsvereins", ermöglicht den Ankauf von Gemälden von Klee, Kandinsky und Chagall. Allerdings werden solch experimentelle Werke erst nach einer „Bewährungsfrist“ von 10 Jahren in den Staatsbesitz übernommen.

Mit der Machtübernahme der Nationalsozialisten 1933 wendet sich das Blatt. Seit langem schon wird Posse von völkisch-nationalen Kräften in Dresden angegriffen. Unter dem Nazi-Regime passt er sich schrittweise an und hängt zahlreiche Bilder ab; 1937 werden über 50 Werke als „entartete Kunst“ beschlagnahmt, die zum Teil der Staatlichen Galerie gehören, zum Teil dem Patronatsverein und zum Teil der Stadt Dresden, die mit Leihgaben die „Moderne Galerie" unterstützt. Im folgenden Jahr besucht Hitler die Gemäldegalerie. Von Posses Sachkenntnis der Alten Meister beeindruckt, macht er ihn zum Sonderbeauftragten für sein geplantes Führermuseum in Linz. Gut drei Jahre lang, bis zu seinem Tod 1942, trägt Posse Bilder für Hitlers Museumsprojekt zusammen, maßgeblich aus geraubten Beständen jüdischen Eigentums.

“For Kokoschka, children are very special. They are valuable, they are bearers of experience, and they experience things very intensively...”

In 1921, Oskar Kokoschka painted a portrait of Gitta Wallerstein, daughter of an art dealer friend of his. At that time, Kokoschka was 35, the youngest professor at the Dresden Academy of Art, his wild years as the enfant terrible of the Vienna art scene behind him. Now, the portraits he was painting are almost psychological profiles of his sitters. This work, for instance, reflects the shy and earnest gaze of a young girl approaching adolescence. Kokoschka has painted Gitta in luminous blue and green tones in front of a broad river landscape. Curator Birgit Dalbajewa again:

"Gitta Wallerstein was ten years old when she sat for Kokoschka in his art academy studio on the Brühlsche Terrasse next to the Albertinum. Later, she recalled how incredibly nervous she was with this man with his Viennese accent. Since she was allowed to perform her gym exercises in his studio, she could move freely. From time to time, Kokoschka took a tube of colour, held it against her dress and asked her quite seriously whether, in her view, she thought the colour was the right one.”

In those days, Gitta Wallerstein was already taking dancing lessons. She went on to become a solo dancer at Berlin’s State Opera House. But since she came from a Jewish family, after the Nazi seizure of power she was banned from performing. In 1939, she emigrated to the USA. There, she initially worked as a dancer, but later became a doctor’s receptionist and a radiology assistant. Until her death in 2008, Gitta Wallerstein worked for human rights and cared for people with HIV/AIDS. She and Oskar Kokoschka remained friends for life.

By the end of the First World War, the modern collection in the Dresden Paintings Gallery had acquired Realist, Symbolist, and other such works, but almost no paintings from the latest, cutting-edge art movements – no Gauguin or Van Gogh, and only a few Expressionists. Initially, Paintings Gallery Director Hans Posse was powerless in the face of a conservative acquisitions commission made up of venerable art professors and Saxon’s crown prince – but in 1919, after the collapse of Imperial Germany, that changed radically.

Now, the arts pages in Dresden’s newspapers called for the gallery to be “rejuvenated”. Posse pushed through measures to replace the acquisitions commission with an advisory committee open to progressive ideas. Despite the limited finances available, he gradually built up a collection of modern art, starting with works by Kokoschka, Heckel, and Pechstein. With these works, Posse shaped the Modern Gallery. Above all, from 1925, he could add major works by Munch, Kokoschka, Beckmann and many others to the collection, initially also shown in the Semperbau in the Zwinger. Thanks to the civil society support of a Friends Association, it was also possible to acquire paintings by Klee, Kandinsky and Chagall – although such experimental works were only officially taken into the state collection after a probationary period of ten years.

The tide turned, though, after the Nazi Party came to power in 1933. For a long time, Posse had been attacked by “blood and soil” nationalist circles in Dresden. Under the Nazi regime, he gradually adjusted to the new conditions, taking down many paintings. In 1937, over 50 works were confiscated as “degenerate art” – paintings partly belonging to state gallery, partly to the Friends’ Association, and partly to city of Dresden which supported the Modern Gallery with loans. The following year, Hitler visited the Paintings Gallery. Impressed by Posse’s expertise in works by the Old Masters, Hitler appointed him the Special Envoy for his planned museum project in Linz. For nearly three years until his death in 1942, the works Posse collected for the planned Führer Museum were mostly paintings looted from Jewish owners.

"Děti pro Kokoschku znamenaly něco zvláštního. Jsou pro něj jedinečné a mají schopnost prožívat zážitky obzvlášt intenzívně -"

Roku 1921 Oskar Kokoschka portrétoval Gittu Wallerstein, dceru jednoho přítele, který obchodoval s uměním. Kokoschkovi tenkrát bylo 35 let a byl nejmladším profesorem na drážďanské akademii umění. Čas, kdy jako "Enfant terrible" vídeňské umělecké scény nedbal na společenské zvyky a šokoval společnost svým chováním, už měl za sebou. Portéty, které nyní maluje, jsou téměř psychogramy. Na zdejším obraze zachycuje vážnou a plachou pozornost dospívající dívky. Kokoschka ji zobrazil v jasných odstínech modré a zelené před říční krajinou. Kurátorka Birgit Dalbajewa vypráví:

"Gittě Wallersteinové bylo deset let, když Kokoschkovi seděla modelem v jeho ateliéru na akademii umění na Brühlské terase vedle Albertina. Vyprávěla, že tenkrát byla velmi vzrušená: Tento pán s vídeňským dialektem ji neprve přiváděl do rozpaků. V ateliéru se prý mohla naprosto volně pohybovat a provádět své taneční cviky. Malíř prý občas vzal dokonce tubu s barvou, přiložil ji k jejím šatům a s naprostou vážností se jí zeptal, jestli si myslí, že se zvolený odstín hodí."

Gitta Wallersteinová již tenkrát chodila na taneční hodiny. Později byla sólistkou na berlínské Státní opeře, ale protože byla židovského původu, ztratila během vlády nacistů své místo a roku 1939 emigrovala do USA. Tam zpočátku ještě vystupovala jako tanečnice, později ale pracovala jako zdravotní sestra a asistentka na radiologickém oddělení. Až do své smrti v roce 2008 se angažovala za lidská práva a starala se o nemocné AIDS. S Oskarem Kokoschkou ji spojovalo celoživotní přátelství.

Sbírka moderních mistrů v Drážďanech vlastní až do konce první světové války sice umělecká díla realistů, symbolistů atd., ale prakticky žádné obrazy nejnovějších, současných uměleckých směrů: žádného Gauguina, žádného van Gogha, jen několik málo expresionistů. Ředitel sbírky Hans Posse je tehdy ještě bezmocný vůči konzervativnímu postoji nákupní komise, skládající se ze ctihodných profesorů a saského korunního prince.

Roku 1919 se ale situace změnila. Feuilletony v drážďanském tisku vyzývaly k „omlazení“ umělecké sbírky a Possemu se podařilo prosadit, že nákupní komise byla nahrazena mnohem pokrokovějším sborem poradců. Navzdory finančním potížím se nyní podařilo postupně vybudovat sbírku moderního umění – Hansem Possem označovanou jako „Moderní galerii“. Obsahovala například díla Kokoschky, Heckela a Pechsteina. Především po roce 1925 se Possemu podařilo získat významná díla od Muncha, Kokoschky, Beckmanna a mnoha dalších. Jejich obrazy byly nejprve vystavovány v muzeu Semperbau a ve Zwingeru. Občanské nasazení a angažmá spolku přátel, tzv. „Patronátního spolku“, umožnily nákup obrazů také od Kleea, Kandinského a Chagalla. Tato experimentální díla však přecházejí do vlastnictví státu až po uplynutí tzv. „zkušební doby“, která trvá deset let.

Když roku 1933 převzali moc nacisté, situace se změnila. Již dlouho byl Posse vystaven útokům nacionalistického hnutí v Drážďanech. Za nacistického režimu se Posse postupně přizpůsobil a podrobil vládnoucímu režimu a nechal v galerii sundat četná díla. Roku 1937 je zabaveno přes 50 obrazů jako „zvrhlé umění“, z nichž část patřila Státní galerii, část Patronátnímu spolku a část městu Drážďany, jež „Moderní galerii“ podporovalo výpůjčkami. V následujícím roce navštívil galerii Hitler, který byl ohromen Posseho znalostmi umění starých mistrů, a proto jej jmenoval zvláštním komisařem pro své muzeum, které plánoval v Linci. Více než tři roky, až do své smrti roku 1942, Posse sbíral a skupoval obrazy pro Hitlerův muzejní projekt, přičemž většina děl pocházela z vyvlastněného a zabaveného židovského majetku.

- Ort & Datierung

- 1921

- Material & Technik

- Öl auf Leinwand

- Dimenions

- 85 x 60 cm (Katalogmaß 2010) 111,5 x 86,7 x 5 cm (Rahmenmaß, Tobias Lange, 26.04.2010)

- Museum

- Galerie Neue Meister

- Inventarnummer

- Inv.-Nr. 2014/04