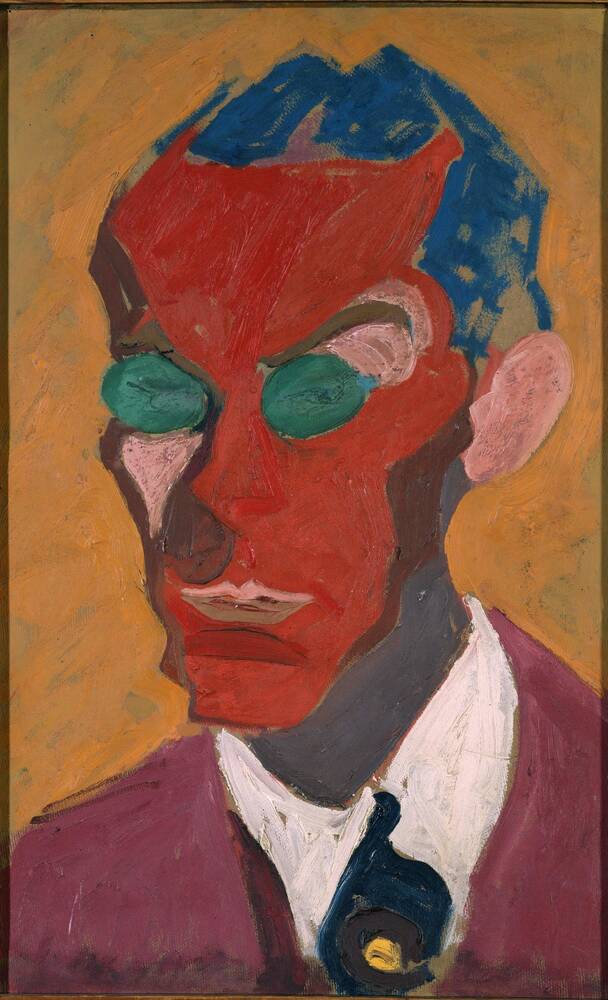

"Roter Klang": So hat der Maler Carl Lohse dieses ausdrucksvolle Bildnis genannt. Die Komposition ist verwegen: Lohse setzt einfach große Farbflächen nebeneinander. Das Gesicht des jungen Mannes modelliert er grob mit breiten Pinselstrichen in leuchtendem Rot; die Brillengläser malt er im Kontrast dazu in schrillem Grün.

Den eleganten jungen Mann hatte Lohse im sächsischen Bischofswerda kennengelernt. Arnold Vieth von Golßenau gehörte zum Freundeskreis jener Familie, bei der Lohse seit 1919 zu Gast war und die den mittellosen Künstler finanziell unterstützte. Der Adlige, im Ersten Weltkrieg Offizier und Kompanieführer, studierte damals Jura, aber auch Kunstgeschichte; er sollte sich bald darauf als Kunsthändler betätigen und wurde unter dem Pseudonym Ludwig Renn als Schriftsteller bekannt. Lohse empfand ihn seinerzeit offenbar als temperamentvoll und malte das Gesicht vielleicht auch deshalb in feurigem Rot.

Das längliche Antlitz mit den vorstehenden Wangenknochen muss Lohse sehr fasziniert haben, denn er schuf den Kopf auch als weiße Gipsplastik. Eine höchst ungewöhnliche Arbeit, meint die Kuratorin Birgit Dalbajewa:

„man muss sich das vorstellen, die Hände des Bildhauers in dem feuchten Gips, das Auge ist eine Öffnung, wie es überhaupt nicht üblich ist in der Plastik, die Ohröffnung ist eine tiefe Windung hinein gewissermaßen in die Innereien des Kopfes, die einzelnen Fetzen der Haare, die Stirnwulst, die Ohren stehen von dieser Gesamtform so ab: ein so bewegtes Bildnis, die Lippen flattern geradezu, und in dieser Größe, das gibt es in der deutschen Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts kein zweites Mal.“

Weitere Medien

Für die Künstlergeneration, die Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts geboren war, bildete der Erste Weltkrieg einen radikalen Einschnitt, der ihr Leben und ihre Kunst veränderte. So auch für Carl Lohse. Die Laufbahn des Hamburgers hatte vielversprechend begonnen. Schon mit 15 besuchte er die Kunstgewerbeschule. 1912 erhielt der 17Jährige ein Stipendium an der Kunsthochschule in Weimar. Dort blieb er nicht lange; auf der Suche nach seinem eigenen künstlerischen Weg zog er auf den Spuren Vincent van Goghs nach Holland, bis ihn der Kriegsbeginn 1914 zurück nach Deutschland zwang. Vergeblich bewarb sich der junge Lohse um eine Laufbahn als Reserveoffizier, die ihm vielleicht den Fronteinsatz erspart hätte:

„Gerade die Absolventen der Kunstgewerbeschulen wie Carl Lohse und Otto Dix waren nicht in der Etappe eingesetzt, sondern wirklich in den Schützengräben an vorderster Front und haben die ganz unmittelbaren Kriegserlebnisse,“

während Künstler, die an den Akademien studierten, eher als Offiziere am Krieg teilnahmen, so die Kuratorin Birgit Dalbajewa. Der 20jährige Lohse kämpft 1916 als Soldat in der Schlacht an der Somme, der wohl grauenvollsten Schlacht an der Westfront. Seine Kompanie wird verschüttet, er allein überlebt. Nach drei Jahren englischer Kriegsgefangenschaft und Schwerstarbeit in den Steinbrüchen von Calais kehrt er zurück nach Hamburg. Mittellos entlassen findet er Unterstützung: Eine ehemalige Mitschülerin vermittelt ihm den Kontakt zu einem Mäzen, einem kunstsinnigen Fabrikaten, der den jungen Maler als Gast in seinem Haus im sächsischen Bischofswerda aufnimmt. Für Lohse beginnt eine intensive Schaffensphase: In waghalsigen, expressionistischen Bildern setzt er sich mit seinen traumatischen Fronterlebnissen auseinander. Seine ersten Gemälde zeigen Skelette – das Zerbersten von Körpern – das Zersplittern einer Welt, die keinen Halt mehr bietet.

Artist Carl Lohse called this impressive portrait Roter Klang – ‘Red Sound’. A daringly bold composition, Lohse simply sets large areas of colour next to each other. The young man’s face is roughly modelled in brilliant red applied in broad brushstrokes, contrasting vividly with the garish green of the lenses of his glasses.

This elegant young man is Arnold Vieth von Golßenau. In 1919, Lohse, an impoverished artist, was staying in Bischofswerda, Saxony with a family who financially supported him. There, he met Von Golßenau, one of the family’s circle of friends. Born into an aristocratic family, Von Golßenau had served as an officer and company commander in the First World War, before studying law and art history. Later, he began to work as an art dealer and also launched a successful career as a writer under the pseudonym Ludwig Renn. Possibly Lohse found Von Golßenau very spirited and feisty in his views, and so painted his face a fiery red.

But certainly Lohse was fascinated by the elongated facial features and prominent cheekbones, since he also took Von Golßenau’s portrait as the subject of a white plaster sculpture. A highly unusual work, as curator Birgit Dalbajewa explains:

“...You can just imagine the sculptor’s hands working the wet plaster. The eye is an opening, something hardly found at all in sculpture, the ear is a deep whorl leading, in a certain sense, into the innards of the head. And with the single scraps of hair, the bulging forehead, the ears sticking out from this overall shape – it creates such a vibrant likeness that the lips seem to be quite literally trembling. And in terms of its size, there is really nothing else like it in German twentieth century art.”

For the generation of artists born in the late nineteenth century, the First World War was a radical break, a watershed in their lives and art – just as it was for Carl Lohse. Born in Hamburg in 1895, he showed considerable promise in his early years. At the age of 15, he was already attending a school of arts and crafts. Two years later in 1912, he was awarded a scholarship to study at the art college in Weimar. But he did not stay there for long. Driven by his quest to find his own artistic voice, he moved to Holland to find a new inspiration in tracing the footsteps of Vincent van Gogh. In 1914, though, with the outbreak of war, he returned to Germany. Lohse applied to join the army as a reserve officer, which might well have spared him front line service.

“The graduates of arts and crafts colleges especially, such as Carl Lohse and Otto Dix, were not deployed at the army bases, but sent straight into the trenches on the front lines, and experienced the war directly at first hand,”

... and, curator Birgit Dalbajewa added, artists who had studied at state art academies tended to be given the rank of officers. In 1916, Lohse, then 20 years old, saw action in the Battle of the Somme, probably the most brutal and deadliest military action on the western front. Lohse’s company were buried when a shell collapsed their trench, and he was the only one to survive. Later he was taken prisoner by the British forces. After three years of heavy work as a prisoner of war in the Calais quarries, he returned to Hamburg. Destitute, he was helped by a young woman painter who had studied art with him. She introduced him to an art-loving factory owner in the small town of Bischofswerda in Saxony.

In his new patron’s house, freed from his financial worries, Lohse could return to painting – the start of an intensive creative phase. In audacious, expressionist pictures, he grappled with his traumatic experiences on the front lines. His first paintings show skeletons, bodies split and bursting – a shattered world offering no security, and no fixed point of support.

"Červený tón" - tak pojmenoval malíř Carl Lohse tento expresívní portrét. Jeho kompozice je odvážná: Lohse pracuje s velkými barevnými plochami, které jednoduše řadí vedle sebe. Tvář mladého muže hrubě modeluje pomocí širokých tahů štětcem v jasně červené barvě a jako kontrast k tomu skla brýlí v křiklavé zelené.

Lohse se s tímto elegantním, mladým mužem seznámil v saské Bischofswerdě. Arnold Vieth patřil k okruhu přátel rodiny, u které Lohse od roku 1919 jako host bydlel a která jej finančně podporovala. Vieth pocházel ze šlechtické rodiny, byl za první světové války důstojníkem a velitelem a tenkrát studoval práva, ale také dějiny výtvarného umění. Nedlouho potom začal obchodovat s uměním a se poměrně známým jako spisovatel pod pseudonymem Ludwig Renn. Lohsemu v té době očividně připadal velmi temperantní a možná z tohoto důvodu namaloval jeho obličej v ohnivě červených barvách.

Jeho podlouhlá tvář s vystouplými lícními kostmi musela malíře velmi zaujmout, neboť Lohse jeho portrét zrealizoval také jako sochu z bílé sádry. Jak míní kurátorka Birgit Dalbajewa, jedná se o velmi neobvyklé dílo:

"člověk si tu situaci musí představit, ruce sochaře jsou ponořené do vlhké sádry. Oči jsou dva velké otvory, což u soch normálně není vůbec běžné, ušní otvory jakoby se v podivných záhybech vinuly takříkajíc přímo dovnitř hlavy samé, jednotlivé divoké prameny vlasů, masívní a vyboulené čelo, uši odstávají od celkového tvaru sochy: Je to velmi neklidný a téměř znepokující portrét, rty jako by se téměř třepotaly. A to vše v těchto rozměrech - to v německém umění 20. století už podruhé nenajdete."

Pro generaci umělců narozených na konci 19. století znamenala první světová válka radikální zlom, který změnil jejich život i uměleckou tvorbu. To platí i pro Carla Lohseho. Kariéra umělce pocházejícího z Hamburku začala slibně. Již v 15ti letech navštěvoval Umělecko-průmyslovou školu a roku 1912 získal jako sedmnáctiletý stipendium na akademii umění ve Výmaru. Nezůstal zde však dlouho. Hledal svou vlastní uměleckou cestu a vydal se po stopách Vincenta van Gogha do Holandska, dokud ho začátek války v roce 1914 nepřinutil vrátit se zpět do Německa. Mladý Lohse se neúspěšně ucházel o kariéru záložního důstojníka, která by mu bývala ušetřila nasazení na frontě:

„Právě absolventi uměleckoprůmyslových škol jako Carl Lohse a Otto Dix nebyli nasazeni v zázemí, nýbrž přímo v zákopech na frontě a poznali hrůzy války bezprostředně z vlastní zkušenosti,“

zatímco umělci, kteří studovali na akademiích umění, sloužili ve válce spíše jako důstojníci, jak vypráví kurátorka Birgit Dalbajewa. Dvacetiletý Lohse bojuje jako voják roku 1916 v bitvě na Somně, pravděpodobně nejhrůznější bitvě na západní frontě. Jeho rota byla po výbuchu zasypána, on jediný přežil. Po třech letech v anglickém zajetí a těžké práci v lomech v Calais se Lohse mohl vrátit do Hamburku.

Když je bez jakýchkoli finančních prostředků propuštěn, najde podporu od jedné bývalé spolužačky: Ta mu zprostředkuje kontakt k jednomu továrníkovi, který je milovníkem umění a který jej jako hosta pozve do svého domu v saské Bischofswerdě. Pro Lohseho začíná intenzívní tvůrčí fáze: V odvážných expresionistických obrazech se vyrovnává se svými traumatickými zážitky z války. Na svých prvních obrazech zobrazuje kostry – roztrhaná těla – rozpadající se svět, který už nenabízí žádnou oporu.

- Ort & Datierung

- 1919

- Material & Technik

- Öl auf Pappe

- Dimenions

- 71,5 x 45,5 cm (Katalogmaß 2010) 71 x 46 cm (Katalogmaß 1987) 71 x 46 cm (Inventurmaß, 29.04.2010) 82 x 55,5 x 2,5 cm (Rahmenmaß, Tobias Lange, 29.04.2010)

- Museum

- Galerie Neue Meister

- Inventarnummer

- Inv.-Nr. 79/31