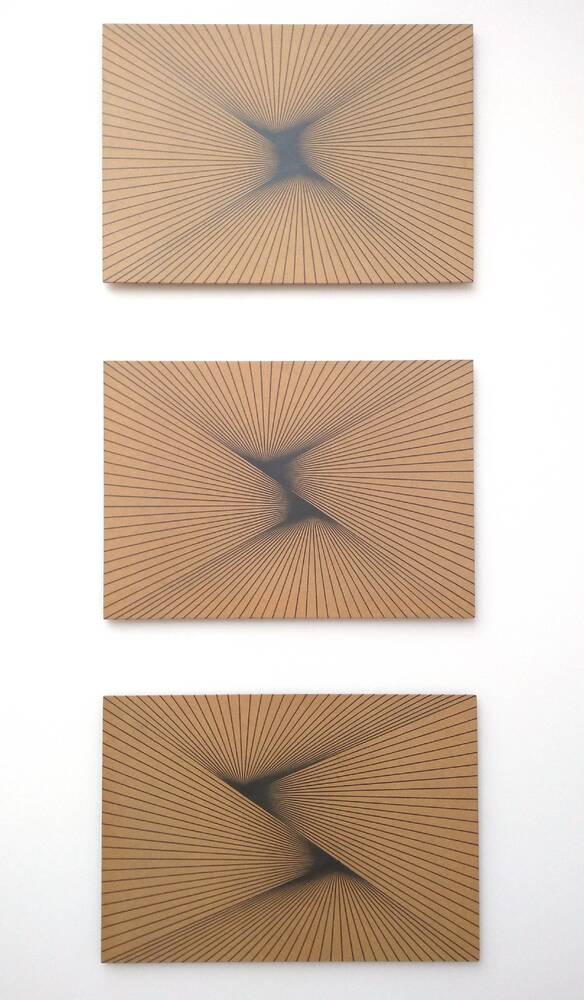

„Ich wollte nichts anderes als dicht aneinander stoßende und weit auseinander laufende Schluchten schaffen, um verschiedene Tiefen zu bekommen. [...] Es gibt kein Geheimnis, es ist alles ziemlich profan.“

So beantwortete Karl-Heinz Adler im hohen Alter die Frage nach seinen seriellen Lineaturen – einer Werkserie, die er in den 1960er Jahren begonnen hatte.

Die präzise Auseinandersetzung mit algorithmisch organisierten Formen und die serielle Arbeitsweise lässt Adlers Verbindung zu Naturwissenschaft und Technik erahnen. Zugleich entsteht durch diese Formen ein magischer Bildraum mit einer unergründlichen Tiefe, der unser rationales Verhältnis zur Welt, unsere Vorstellung von Raum und Zeit auf die Probe stellt. Malerei war für Adler, so fasste er es einmal zusammen, philosophische Weltbetrachtung mit Hilfe bildnerischer Mittel.

Der gelernte Musterzeichner für Teppiche studierte in der Nachkriegszeit an den Kunsthochschulen in West-Berlin und Dresden und wurde 1953 Mitglied im Verband Bildender Künstler der DDR. Eigentlich passte er nicht so recht ins System, denn stets bewegte er sich fernab von figurativer Malerei und sozialistischem Realismus. Adler ergründete vor allem das Zusammenspiel von Farben und Formen und wurde so zu einem Vertreter der Konkreten Kunst, die in der DDR eigentlich nur geduldet wurde. Als Kunst am Bau war sie aber durchaus willkommen. Das bekannteste Beispiel für Adlers Schaffen in diesem Bereich ist sein zusammen mit Friedrich Kracht entwickeltes Betonformsteinsystem, das ab den 1970er-Jahren industriell gefertigt und in der DDR vielerorts an Fassaden verbaut wurde, und das zu ornamentalen Wänden zusammengefügt werden konnte, mit denen urbane Freiflächen gegliedert und ästhetisch aufgewertet wurden.

Weitere Medien

Wie alle avantgardistischen Kunstrichtungen war auch die konkrete Kunst während des Nationalsozialismus als „entartet“ geschmäht worden. Nach Kriegsende versuchten dann viele Künstler, an die Moderne anzuknüpfen, und im Sommer 1946 versprach die Erste Allgemeine Deutsche Kunstausstellung in Dresden eine große Offenheit für alle Strömungen der Avantgardekunst. Ende 1948 setzte jedoch auf dem Gebiet der späteren DDR eine Kehrtwende ein. Die neue Leitlinie des „Sozialistischen Realimus“ forderte, dass Kunst gegenständlich sein und das Ideal des sozialistischen Menschen vermitteln sollte. Nicht-gegenständliche Strömungen wie die konkrete Kunst wurden als „formalistisch“ abgelehnt und waren im offiziellen Kunstbetrieb der DDR unerwünscht.

Die konkrete Kunst führte seitdem eine Nischenexistenz. So arbeitete zum Beispiel einer der bedeutendsten konkreten Künstler Deutschlands, der Dresdener Hermann Glöckner, lange Zeit allein und zurückgezogen vom Kunstbetrieb der DDR und verdiente sich seinen Unterhalt mit dekorativen Arbeiten am Bau. "Kunst am Bau" war auch das Arbeitsfeld der konkreten Künstler Karl-Heinz Adler und Friedrich Kracht. Beide hatten ihr Studium in Dresden abgeschlossen und eine Serie von 12 Formsteintypen aus Beton entwickelt, die zu verschiedensten Mustern zusammengesetzt werden konnten und viele DDR-Fassaden schmückten; zudem schufen Adler und Kracht auch Skulpturen und Brunnen. Der künstlerische Wert solcher Arbeiten wurde von den Kulturfunktionären der DDR jedoch verkannt; sie stuften sie ausschließlich als dekorative und ingenieurtechnische Leistungen ein. Was immerhin den Vorteil hatte, dass die konkreten Künstler nicht ins Visier der Zensur gerieten und Freiräume zum Arbeiten behielten. Seit den 1970er Jahren kam es in der DDR dann zu einer gewissen Liberalisierung der Kulturpolitik. So erhielt Hermann Glöckner 1984, mit 95 Jahren, den Nationalpreis der DDR Dritter Klasse.

Late in life, Karl-Heinz Adler offered an explanation of his Serial Lines – a series of works started in the 1960s.

“My aim was nothing more than to produce a variety of depths by creating canyons running far apart or colliding with each other. [...] There is no secret to it, it is all rather ordinary.”

Adler’s profound and precise exploration of systematic algorithmic shapes and serial production are informed by his interest in science and technology. At the same time, these forms create a magical pictorial space of an unfathomable depth, testing our rational relationship to the world as well as our concept of space and time. As Adler once said, he viewed painting as a way of philosophically observing the world with the help of visual means.

Originally, he trained as a textile designer at a carpet factory. In the post-war period, he studied at art colleges in West Berlin and Dresden and, in 1953, became a member of the GDR’s Verband Bildender Künstler – East Germany’s Association of Visual Artists. But Adler did not really fit into the GDR system. His artistic work was always far removed from the state-approved figurative art or Socialist Realism. Above all, in his exploration of the interplay of colours and forms he became a proponent of Concrete Art, a movement merely tolerated in the GDR. In contrast, his work in architectural art was certainly welcomed. In that area, Adler is best known for the concrete modular system developed with Friedrich Kracht. From the 1970s, this system was produced industrially and integrated into façades in many places in East Germany. The modular forms also provided ornamental concrete surfaces for decorative walls to structure urban public space and enhance its aesthetic value.

The Nazi regime condemned all avant-garde movements as “degenerate”, just as they did concrete art, a type of non-figurative painting and sculpture. After the end of the war, many artists sought to revisit and revitalise modern art. In summer 1946, the First Art Exhibition of the GDR in Dresden also held out the promise of being open to all avant-garde art movements. By late 1948, though, this policy underwent a U-turn in the Soviet zone, which later became the GDR. The new guiding principle was Socialist Realism – figurative art conveying the ideal of the socialist personality. Abstract, non-representational styles such as concrete art were rejected as “formalist” and had no place in East Germany’s official art world.

Afterwards, concrete art only existed in an artistic niche. For example, Dresden artist Hermann Glöckner, one of Germany’s most important figures in concrete art, worked alone for a long time. Removed from official art circles in East Germany, he earned a living from decorative wall décor for buildings. Concrete artists Karl-Heinz Adler and Friedrich Kracht, who both studied in Dresden, also worked in the field of ornamental architectural art. They developed a series of 12 specially-shaped concrete bricks able to be combined into diverse patterns – a modular design system integrated into many façades in the GDR. In addition, Adler and Kracht also created sculptures and fountains. East Germany’s cultural functionaries, though, failed to recognise the artistic merit of such works, solely seeing their value in terms of engineering and decoration – which at least had the advantage of taking these concrete artists off the radar of state censorship and so giving them more freedom to work. From the 1970s, there were moves to partially liberalise cultural policies in East Germany. In 1984, for instance, Hermann Glöckner, then 95 years old, was awarded the National Prize of the GDR, third class.

„Nechtěl jsem vytvořit nic jiného než těsně přiléhající a široce se rozbíhající soutěsky, abych dosáhl různých hloubek. [...] Není to žádné tajemství, je to všechno poměrně všední.“

Tak Karl-Heinz Adler odpověděl v pokročilém věku na otázku týkající se jeho série děl s lineaturami, kterou započal v 60tých letech minulého století.

Důkladný rozbor algoritmicky uspořádaných forem a sériový způsob práce dávají tušit Adlerův úzký vztah k přírodním vědám a technice. Tyto formace zároveň vytvářejí magický výtvarný prostor s nekonečnou hloubkou, který otřásá naším racionálním vztahem ke světu, naší představou o prostoru a času. Pro Adlera bylo malířství, jak to sám vyjádřil, filozofickou kontemplací světa pomocí výtvarných prostředků.

Adler byl vyučeným kreslířem vzorů koberců a po válce studoval na akademiích umění v západním Berlíně a v Drážďanech. Roku 1953 se stal členem Svazu výtvarných umělců v bývalé NDR. Vlastně do tehdejšího systému příliš nezapadal, protože jeho dílo nebylo figurativní a neodpovídalo představám socialistického realismu. Adler se zabýval především souhrou barev a forem a stal se tak představitelem skupiny „Konkrétní umění“, která byla v NDR pouze tolerována. V architektuře však byla poměrně vítána a připuštěna. Nejznámějším příkladem Adlerovy práce v této oblasti je systém betonových tvárnic, který Adler vyvinul spolu s Friedrichem Krachtem a které se od 70tých let 20. století průmyslově vyráběly a používaly při stavbě průčelí budov. Z těchto betonových tvárnic bylo možné na zdích sestavovat ornamenty, které strukturovaly a esteticky dotvářely volná městská prostranství.

Stejně jako všechny avantgardní umělecké směry bylo také konkrétní umění během vlády národních socialistů odmítáno jako „zvrhlé umění“. Po skončení války se pak mnozí umělci pokoušeli navázat na modernismus. První všeobecná německá výstava umění, která se konala roku 1946 v Drážďanech, byla příznivě nakloněná všem proudům avantgardního umění. Koncem roku 1948 však došlo v pozdější NDR ke zlomu: Nová linie „socialistického realismu“ požadovala, aby umění bylo předmětné a vyjadřovalo ideál socialistického člověka. Nepředmětné, tedy abstraktní proudy jako konkrétní umění bylo odmítáno jako „formalistické“ a na oficiální umělecké scéně NDR bylo nežádoucí.

Konkrétní umění bylo tenkrát pouze tolerováno. Tak například jeden z nejvýznamnějších konkrétních německých umělců, Hermann Glöckner z Drážďan, pracoval dlouhou dobu sám a odloučen od uměleckého světa v NDR. Živil se dekorativními pracemi na stavbách. Uměním v architektuře se zabývali také dva jiní představitelé konkrétního umění: Karl-Heinz Adler a Friedrich Kracht. Oba absolvovali studium v Drážďanech a vyvinuli sérii 12 typů betonových tvárnic, ze kterých bylo možné sestavovat ornamenty a které zdobily mnohá průčelí v NDR. Adler a Kracht tvořili ale také sochy a kašny. Uměleckou hodnotu těchto prací však kulturní funkcionáři NDR neoceňovali a považovali je výhradně za dekorativní a inženýrsko-technické výdobytky. To mělo alespoň tu výhodu, že cenzura nevěnovala konkrétním umělcům žádnou pozornost a ti tak měli možnost volně tvořit. Od 70tých let došlo v NDR k částečné liberalizaci kulturní politiky. Roku 1984, ve věku 95ti let, tak byla Hermannu Glöcknerovi udělana Národní cena NDR třetí třídy.

- Ort & Datierung

- 1989

- Material & Technik

- Graphit auf Holzfaserplatte

- Dimenions

- 99 x 69 cm (je Tafel)

- Museum

- Galerie Neue Meister

- Inventarnummer

- Inv.-Nr. 2019/02