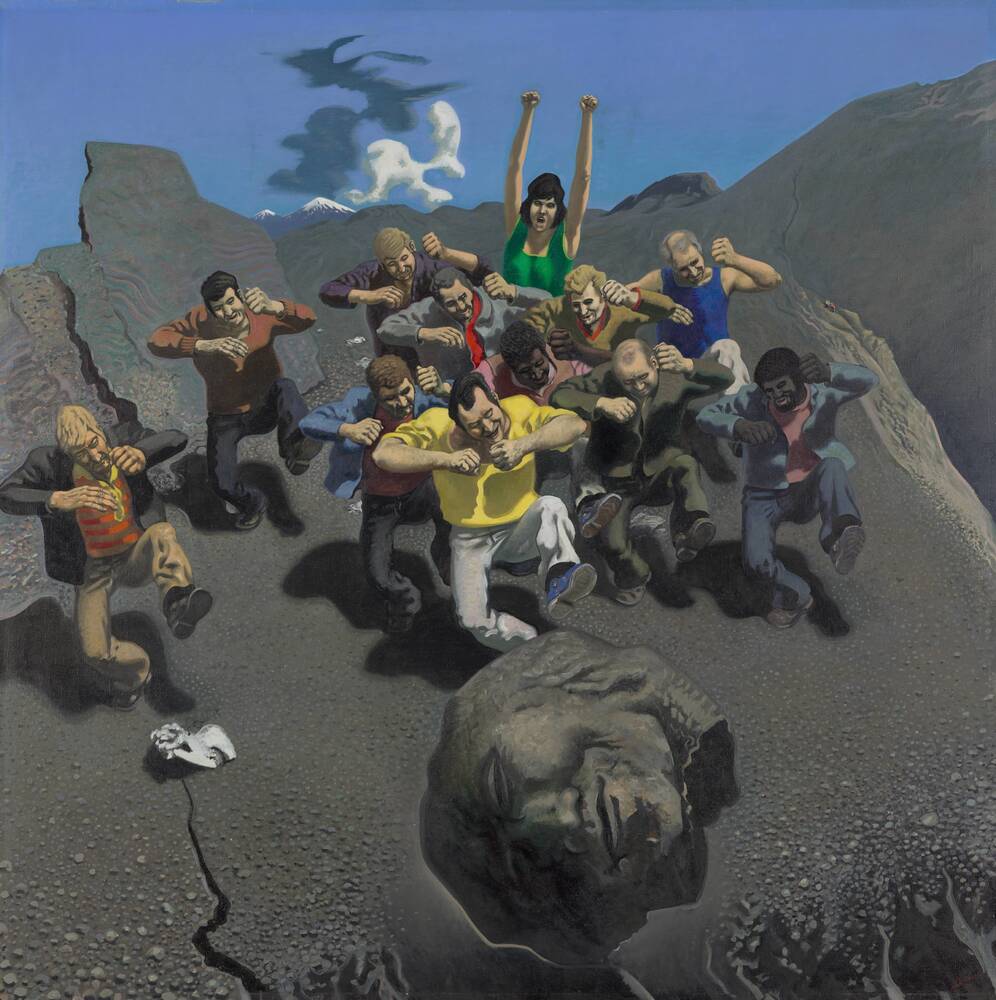

Die Strafe der Götter scheint schrecklich: Immer wieder muss Sisyphos einen Felsbrocken den Berg hinaufrollen, der ihm dann kurz vor dem Gipfel entgleitet. Ein auswegloses Dasein? Wolfgang Mattheuer spielte in seinem Sisyphos-Zyklus aus den 1970er-Jahren drei unterschiedliche Alternativen durch. Im ersten Gemälde entzieht sich Sisyphos der sinnlosen Aufgabe durch Flucht. Er lässt den Stein einfach liegen und rennt mit großen Schritten ins Tal hinab. Im zweiten Bild tanzt ein übermütiger Sisyphos inmitten Gleichgesinnter hinter einem riesigen Steinkopf, der einen Abhang hinunterstürzt. Die Gruppe ist euphorisch. Hat sie mit vereinten Kräften ein Denkmal gestürzt? Die Landschaft aber ist trostlos und das winzige Männchen rechts im Hintergrund erinnert noch an die scheinbar unlösbare Aufgabe.

Im dritten Gemälde trägt Sisyphos nicht mehr die Kleidung eines Arbeiters, sondern Hemd und Krawatte. Beobachtet von drei Männern, rückt er dem Stein nun mit Hammer und Meißel zu Leibe und formt eine geballte Faust – Sinnbild des Widerstands. Die Szene spielt auf einem Schrottplatz, im Hintergrund blasen Schornsteine verschmutzte Luft in den gelben Himmel.

Fazit: Der Mensch ist seinem Schicksal nicht hilflos ausgeliefert, er muss nur handeln. Die Gemälde stecken voller Anspielungen und Metaphern, die unschwer als Kritik an den Missständen in der DDR gelesen werden können, aber auch andere Deutungen zulassen. Und so wurde Wolfgang Mattheuer offiziell geschätzt, heimlich aber von der Staatssicherheit beobachtet. Auch in der Bundesrepublik tat man sich schwer mit der Einordnung, feierte ihn zunächst als Systemkritiker und warf ihm nach der Wende vor, „Staatsmaler“ gewesen zu sein.

Wolfgang Mattheuer gehört neben Bernhard Heisig und Werner Tübke zur ersten Generation der so genannten Leipziger Schule.

Weitere Medien

In den 1960er Jahren entwickelte sich in Leipzig eine besondere Kunstströmung, die "Leipziger Schule"; nach der Wiedervereinigung folgte ihr dann die sogenannte Neue Leipziger Schule. Maßgebliche Vertreter der ersten Generation waren vier Maler der DDR: Wolfgang Mattheuer, Werner Tübke, Bernhard Heisig und Willi Sitte, der allerdings in Halle lebte und arbeitete.

„Wobei man sagen muss, sie bezeichneten sich selbst nicht als Leipziger Schule, sondern sie wurden als Leipziger Schule zusammengefasst, obwohl sie jeder für sich ganz unterschiedlich waren und auch von sich selbst eigentlich abgelehnt hätten, als solche Gruppe zusammengefasst zu werden.“

Stilistisch war die Leipziger Schule keineswegs einheitlich. Was die Künstler jedoch einte, war einerseits ihre beeindruckende handwerkliche Perfektion, und zum anderen, was die Kuratorin Astrid Nielsen ihre "Ideenkunst" nennt:

„Es bestand eine gewisse Konkurrenz zwischen der Malerei in Dresden und der Malerei in Leipzig. Man sagte, in Dresden würde gerade das Malerische besonders bevorzugt werden, und in Leipzig die Ideenkunst. Und das findet man auch, wenn man diese vier Maler miteinander vergleicht, dass sie Ideen vermittelten, auch Lebenswelten, die die DDR in den 70er Jahren in besonderer Weise geprägt haben.“

Die Maler der Leipziger Schule waren über die Grenzen der DDR hinaus bekannt:

„Gerade Anfang der 1970er Jahre erlebten sie einen raschen Aufstieg und prägten auch das Erscheinungsbild der Kunst der DDR oder auch die Wahrnehmung der DDR im Westen Deutschlands in ganz besonderer Weise.

Es ist vielleicht auch noch ganz interessant, dass diese Künstler auch in den Westen reisen durften. Also sie hatten sehr viel Erfolg, und im Gegensatz zu anderen Künstlern, die NICHT reisen durften, hatte gerade Werner Tübke verschiedene Privilegien, er durfte nach Italien reisen, und er war auch auf der documenta beispielsweise 1977 vertreten.“

In Greek mythology, the gods thought up a particularly horrific way of punishing Sisyphus. They condemned him to roll a massive boulder up a hill – and every time it neared the summit, it rolled down and he had to start again. Was this the epitome of a hopeless task? Wolfgang Mattheuer’s Sisyphus cycle from the 1970s plays with three possible alternatives to that narrative. In the first, Sisyphus escapes his senseless fate by running away. He simply stops pushing the boulder and, with huge strides, races for the valley. In the second scene, an exuberant Sisyphus celebrates with helpers as they watch a massive stone head roll down a steep slope. The group is euphoric – have their combined efforts toppled a memorial? The landscape, though, is desolate and bleak. Barely visible in the background on the right, a tiny figure still recalls Sisyphus’s seemingly endless task.

In the third painting, Sisyphus is no longer dressed as a worker, but in a shirt and tie. Watched by three men, he is busily working a huge grey boulder with a hammer and chisel, shaping it into a clenched fist – a symbol of resistance. The scene is set in a junk yard. In the background, tall chimneys send up plumes of grey smoke into the yellow sky.

The message: rather than people simply being helpless in the face of their fate, they have to act. The paintings are packed with allusions and metaphors which can easily be read as criticising the state of affairs in the GDR – yet also offer other interpretations. As a result, Wolfgang Mattheuer was officially praised, yet secretly kept under observation by the Stasi. In West Germany, his work proved similarly difficult to categorise. There, he was initially acclaimed for his critique of the East German system, but shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall was accused of being one of the GDR’s ‘state artists’.

Together with Bernhard Heisig and Werner Tübke, Wolfgang Mattheuer belonged to the first generation of what became known as the Leipzig School.

In the 1960s, the particular style of art developing in Leipzig was dubbed the Leipzig School – and after German reunification this was followed by what became known as the New Leipzig School. The first generation primarily comprised four East German artists: Wolfgang Mattheuer, Werner Tübke, Bernhard Heisig and Willi Sitte, who actually lived and worked in Halle.

“These four artists never referred to themselves as the Leipzig School. But they were combined under that name, even though their art was very different and each of them would have dismissed the idea of belonging to such a group.”

So the Leipzig School was anything but unified stylistically. Nonetheless, these artists shared two things – first, impressive technical perfection and, second, what curator Astrid Nielsen refers to as their approach to an “art of ideas”:

“When it came to painting in Dresden and Leipzig, there was a certain competition between these two cities. Dresden was said to favour in particular the painterly, while in Leipzig the conceptual, the art of ideas, was more important – and that’s what you find too when you compare these four artists. They all convey ideas and life-worlds which, in a special way, shaped the GDR in the 1970s.”M

The Leipzig School artists were also well known outside the GDR:

“In the early 1970s especially, they enjoyed a rapid rise to prominence. Not only did they significantly influence the image of East German art, but also has a major impact on how West Germany perceived the GDR.

It may also be interesting to know that these artists were allowed to travel to the West as well. They were very successful – and in contrast to other artists NOT allowed to travel, Werner Tübke in particular enjoyed various privileges, could go to Italy, and could also, for example, take part in the documenta in Kassel in 1977.”

Trest bohů se zdá být krutý: Sisyfos musí znovu a znovu tlačit obrovský kámen na kopec, ten mu ale vždy kousek pod vrcholem vyklouzne a skutálí se zpět dolů. Beznadějné počínání? Wolfgang Mattheuer ve svém Sisyfovském cyklu ze 70. let navrhuje tři různé alternativy. Na prvním obraze Sisyfos před nesmyslným úkolem prchá pryč. Nechává kámen jednoduše ležet a velkými kroky utíká dolů do údolí. Na druhém obraze tančí rozjařený Sisyfos spolu s ostatními za obrovskou kamennou hlavou, která se kulí ze svahu dolů. Skupina tančících vyzařuje radost, štěstí a nadšení. Svrhli právě spojenými silami pomník? Avšak krajina je pustá a malinký mužík vpravo v pozadí stále ještě připomíná zdánlivě neřešitelný úkol.

Na třetím obraze Sysifos není oblečen do dělnickéhé oblečení, nýbrž má košili a kravatu. Tři muži ho pozorují, jak pomocí kladiva a dláta buší do kamene a vytesává z něj sevřenou pěst – symbol odporu. Scéna se odehrává na vrakovišti a v pozadí z komínů kouří znečištěný vzduch do žluté oblohy.

Shrnutí: Člověk není bezmocný a vydán na pospas svému osudu, musí se jen rozhodnout a jednat. Obrazy jsou plné narážek a metafor, které lze snadno interpretovat jako kritiku tehdejších poměrů v NDR, ale umožňují také jiné interpretace. A tak byl Wolfgang Mattheuer oficiálně sice uznáván, ale zároveň tajně sledován státní bezpečností. Ve Spolkové republice si odborníci také částečně nevěděli rady, kam Mattheuera zařadit. Zpočátku byl oslavován jako kritik systému NDR a po pádu komunismu označován za tak zvaného „státního malíře“.

Wolfang Mattheuer patří spolu s Bernhardem Heisigem a Wernerem Tübkem k první generaci tzv. Lipské školy.

V 60tých letech 20. století se v Lipsku vyvinul nový umělecký směr, „Lipská škola“, na kterou po sjednocení Německa navázala tzv. „Nová lipská škola“. Nejdůležitějšími představiteli první generace byli čtyři malíři z NDR: Wolfgang Mattheuer, Werner Tübke, Bernhard Heisig a Willi Sitte, který ale žil a pracoval v Halle.

„Přičemž však musíme říct, oni sami se neoznačovali jako „Lipská škola“. Pod tímto názvem bylo prostě shrnuto jejich dílo, ačkoli se od sebe značně odlišovali a sami by vlastně toto označení jako skupina odmítli.“

Styl „Lipské školy“ nebyl v žádném případě jednotný. Umělce však na jedné straně spojovala působivá řemeslná dovednost a na straně druhé to, co kurátorka Astrid Nielsenová označuje jako „ideové umění“:

„Mezi malířskou scénou v Drážďanech a v Lipsku existovala určitá konkurence. V Drážďanech se prý kladl větší důraz na malířskou dovednost a v Lipsku na ideové umění. Když porovnáte tyto čtyři malíře, uvidíte to v jejich díle, kde se snažili vyjádřit určité myšlenky a také životní okolnosti, které výrazným způsobem formovaly NDR v 70tých letech.“

Malíři „Lipské školy“ byli známí také za hranicemi NDR:

„Zejména na začátku 70tých let 20. století zažili rychlý vzestup a výrazným způsobem formovaly umění NDR stejně jako jeho vnímání v západním Německu. Možná je zajímavá také skutečnost, že tito umělci směli cestovat i na západ a slavili tak také velké úspěchy. Na rozdíl od jiných umělců, kteří cestovat NESMĚLI, měl zejména Werner Tübke různé výhody a privilegia. Například mu bylo dovoleno cestovat do Itálie či směl vystavovat na documentě roku 1977.“

- Ort & Datierung

- 1976

- Material & Technik

- Öl auf Leinwand

- Dimenions

- 200 x 200 cm (Katalogmaß 2010) 200 x 200 cm (Katalogmaß 1987) 200 x 200 cm (Inventurmaß, 20.05.2010) 208,5 x 208 x 6,5 cm (Rahmenmaß, Tobias Lange, 20.05.2010)

- Museum

- Galerie Neue Meister

- Inventarnummer

- Inv.-Nr. 81/02