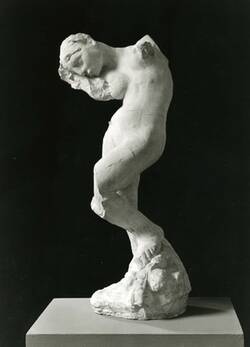

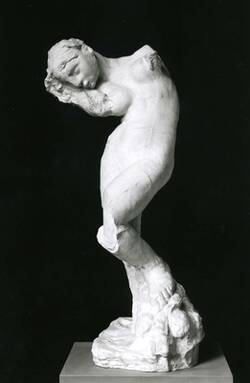

Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts traf Auguste Rodin eine radikale Entscheidung: er erklärte den Torso zum eigenständigen Kunstwerk. Unsere Statue „Die innere Stimme“, der die Arme fehlen und die Beine massiv beschnitten sind, hielt er sogar für seine beste Arbeit. Der jungen Frau wirkt vollkommen in sich gekehrt und sehr verletzlich in ihrer Nacktheit und Versehrtheit.

Bei der „Heroischen Büste“, einem Porträt des Victor Hugo, konzentriert sich alle Aufmerksamkeit auf den nachdenklich geneigten Kopf des Dichters. Beide – der weibliche Torso und die Büste – sind zweifelsohne ausdrucksstarke Skulpturen. Entworfen aber hatte sie Auguste Rodin einst als Teile eines Denkmals. Kuratorin Astrid Nielsen:

„1889 hatte Rodin in Frankreich von der Société des gens de lettres, einem Zusammenschluss von Literaturschaffenden, den Auftrag erhalten, ein Denkmal für Victor Hugo, den großen französischen Dramatiker, Schriftsteller, Romancier und Lyriker zu entwerfen. Rodin schuf verschiedene Entwürfe und auch Modelle dazu, er zeigte einen sitzenden Victor Hugo, einen anderen, einen fast liegenden Victor Hugo, nur mit einem antiken Mantel bekleidet und umgeben von einer Muse, einer tragischen Muse als Sinnbild für die dramatische Dichtkunst Victor Hugos und umgeben von einer stehenden Figur, die den Titel trug ‚la méditation‘, die Meditation oder auch ‚Die innere Stimme‘, was sich wiederum auf einen Gedichtzyklus von Hugo bezog ‚Les voix intérieures‘, ‚Die inneren Stimmen‘.

Das Denkmal wurde schließlich ohne die Assistenzfiguren realisiert. Aber Teile des Entwurfs führte Rodin in größerem Format als Einzelwerke aus. Beim Porträt des Dichters ließ er die stützende Hand weg. Die „Innere Stimme“ ließ er ganz bewusst so angeschnitten, wie sie ursprünglich in das Denkmal eingepasst war. Aber der erzählerische Zusammenhang spielte nun keine Rolle mehr.

Weitere Medien

Die Moderne in der Skulptur beginnt Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts mit Auguste Rodin, sagt Kuratorin Astrid Nielsen:

„Also für ihn war ein Fragment tatsächlich ein vollständiges Werk. Das wäre in der Renaissance undenkbar gewesen, einen nicht kompletten Menschen darzustellen. Und auch während des Barock war das eigentlich undenkbar. So war es auch eine Hauptbeschäftigung oder Haupteinnahmequelle barocker Bildhauer gerade in Rom, Antiken zu ergänzen und zu vervollständigen. Rodin selbst besaß eine große Antikensammlung, die sich auch heute noch im Musée Rodin befindet, das heißt, er selbst kannte antike Fragmente aus der eigenen Sammlung, aus der eigener Anschauung. Das war ihm Inspiration genug, so radikal vorzugehen und seine Figuren in unterschiedlichster Art und Weise den Gesamtzusammenhängen, anderen Entwürfen zu entnehmen, sie zu fragmentieren und als komplette Kunstwerke auszustellen.“

Bei Georg Treu, dem damaligen Direktor der Dresdner Skulpturensammlung, stieß diese Haltung auf großes Interesse. Schon 1897, direkt nach der Internationalen Kunstausstellung in Dresden, erwarb er die „Innere Stimme“ als Gipsfigur direkt beim Künstler. Bei vielen Besuchern aber stieß der Torso auf Unverständnis und Ablehnung. Und in der Presse warf man Rodin sogar vor, verrückt zu sein.

Die Geschichte der „Innere Stimme“ geht übrigens noch weiter zurück. Ursprünglich hatte Rodin die Figur für sein berühmtes „Höllentor“ entworfen. Dieses Portal, auf dem er sich mit Dantes „Göttlicher Komödie“ auseinandersetzte, war für einen Museumsneubau in Paris gedacht, der nie realisiert wurde. Das Tor beschäftigte Rodin Zeit seines Lebens, wurde aber nie vollendet. Doch er nutzte es als großen Fundus, aus dem er immer wieder Figuren entnahm und sie ein Eigenleben führen ließ. Auch der berühmte „Denker“ stammt übrigens aus diesem Repertoire.

In the late nineteenth century, Auguste Rodin took a radical decision – he declared a torso to be an independent art work. What’s more, he even claimed this Inner Voice statue was his best work – even though the arms are missing, and the legs heavily cut away. The young woman seems entirely absorbed in herself, vulnerable in her disfigurement and nakedness.

The Heroic Bust, a portrait of the writer Victor Hugo, focuses entirely on the writer’s head, bowed in thought. Without doubt, both these works – the female torso and the portrait bust – are strongly expressive sculptures. Originally, though Rodin designed them as part of a monument. Curator Astrid Nielsen:

“In 1889, the Société des gens de lettres, a French writers’ association, commissioned Rodin to design a monument commemorating Victor Hugo, the great French dramatist, writer, novelist, and poet. Rodin worked on various designs and the corresponding models. In one of them Victor Hugo is sitting, while another shows him almost fully reclined, dressed in a classical-style robe and flanked by two allegorical figures – the Tragic Muse, a reference to Victor Hugo’s dramatic works, and a standing figure called ‘la méditation’, meditation or the ‘Inner Voice’, alluding to a cycle of Hugo’s poems entitled Les voix intérieures, ‘Inner Voices’.

Ultimately, the monument was realised without the flanking figures. However, Rodin then worked up parts of his draft design as larger individual figures. In his portrait of Victor Hugo, he left out the supporting hand. He also deliberately left his “Inner Voice” figure cropped just as it originally fitted into the monument. But then as now, without the narrative context, it stands only for itself.

According to curator Astrid Nielsen, modern sculpture began in the late 1800s with Auguste Rodin:

“In his view, a fragment was actually a finished work. (…) In the Renaissance, it would have been unthinkable to leave a figure incomplete – something equally unimaginable in the Baroque period as well. In particular, many Baroque sculptors in Rome were mainly employed to restore and complete classical works, and this was a main source of their income. Rodin owned a large collection of sculptures from antiquity – and today these works are also on show in the Musée Rodin in Paris. So Rodin was familiar with viewing fragments of classical sculpture in his own collection, and that was also inspiration enough for such a radical break. In various ways, he removed his figures from overall contexts and other preliminary models, fragmenting them and displaying them as full works of art.”

Georg Treu, then Director of the Sculpture Collection, was extremely interested in Rodin’s approach. As early as 1897, immediately after the International Art Exhibition in Dresden, he acquired a plaster figure of the Inner Voice directly from Rodin himself. But many visitors disliked the torso and found it incomprehensible. The press even accused Rodin of being crazy.

Incidentally, there is more to the backstory of Rodin’s Inner Voice. Originally, he had designed the figure as part of his famous Gates of Hell project, a massive portal for a new museum in Paris, with figures and groups all inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy. Rodin spent many years working on the portal though, ultimately, it was never finished. Nonetheless, he used it a vast resource and inspiration, constantly taking figures from it to turn into individual works – just as he did with his famous sculpture The Thinker.

Na konci 19. století učinil Auguste Rodin radikální rozhodnutí: Definoval torzo jako samostatné umělecké dílo. Za své nejlepší dílo považoval dokonce naši sochu Vnitřní hlas, které chybí paže a velká část noh. Mladá žena působí ve své nahotě a se svým poničeným tělem velmi zahloubaně a zranitelně.

U Heroické busty – portrétu Victora Huga – se veškerá pozornost soustředí na básníkovu zamyšleně skloněnou hlavu. Obě díla – ženské torzo a busta – jsou nepochybně velmi expresivní sochy. Auguste Rodin je kdysi navrhl jako části pomníku. Kurátorka Astrid Nielsenová:

„Roku 1889 byl August Rodine pověřen francouzskou společností Sdružení literátů, která sdružovala spisovatele, aby navrhl pomník Victora Huga, velkého francouzského dramatika, spisovatele, romanopisce a lyrika. Rodin vytvořil různé návrhy a také modely. Zobrazil Victora Huga sedíc, ale také téměř v leže, oblečeného pouze v antickém rouše a obklopeného múzou, tragickou múzou jako symbolem Hugovi dramatické poezie, a stojící postavou, která nesla název La méditation, tedy rozjímání nebo také Vnitřní hlas. Tento název odkazoval na cyklus Hugových básní Vnitřní hlasy.

Památník byl nakonec realizován bez vedlejších postav. Z částí původního návrhu však vznikla jednotlivá díla ve větším formátu. Portrét básníka vytvořil Rodin bez podpírající ruky. Vnitřní hlas ponechal záměrně tak, jak byl původně myšlen pro pomník, ale narativní kontext tu již nehrál žádnou roli.

Počátek moderního sochařství se datuje na konec 19. století s dílem Augusta Rodina, jak říká kurátorka Astrid Nielsenová:

„Pro něj bylo torzo či fragment lidského těla opravdu kompletním dílem. (...) V době renesance bylo naprosto nepředstavitelné zobrazit lidské tělo jako nekompletní. A také v období baroka to vlastně bylo nemyslitelné. Proto bylo jednou z hlavních činností a hlavním zdrojem příjmů barokních sochařů právě v Římě doplňovat a dokončovat antická díla. Také Rodin vlastnil velkou sbírku antických děl, která se dodnes nacházejí v Rodinově muzeu. To znamená, že znal antické fragmenty z vlastní sbírky a z vlastního pozorování. To mu bylo dostatečnou inspirací k tomu, aby postupoval tak radikálně a své figury nejrůznějšími způsoby vyjímal z celkových souvislostí či z jiných předloh, fragmentoval je a vystavoval jako kompletní umělecká díla.“

Tento postoj velmi zaujal Georga Treua, tehdejšího ředitele drážďanské sochařské sbírky. Již roku 1897, bezprostředně po Mezinárodní výstavě umění v Drážďanech, zakoupil přímo od Rodina sádrový odlitek Vnitřní hlas. Torzo se však u mnoha návštěvníků setkalo s nepochopením a odmítnutím. V tisku se dokonce ozvaly hlasy, že se Rodin zbláznil.

Historie Vnitřního hlasu však sahá ještě dále. Rodin původně postavu navrhl pro svou slavnou Bránu pekel, ve které se zabýval Dantovou Božskou komedií. Tento portál byl určen pro novou budovu muzea v Paříži, která však nebyla nikdy realizována. Brána zaměstnávala Rodina po celý jeho život, ale nikdy ji nedokončil. Používal ji jako velký fundus, z nějž opakovaně vyjímal jednotlivé postavy jako samostatná umělecká díla. Odsud také pochází jeho slavný Myslitel.

- Ort & Datierung

- Paris, 1886

- Material & Technik

- Gips

- Dimenions

- H: 149,5 cm, B: 70 cm, T: 60 cm

- Museum

- Skulpturensammlung

- Inventarnummer

- ASN 4816