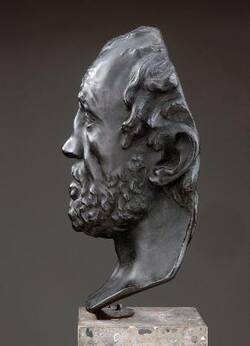

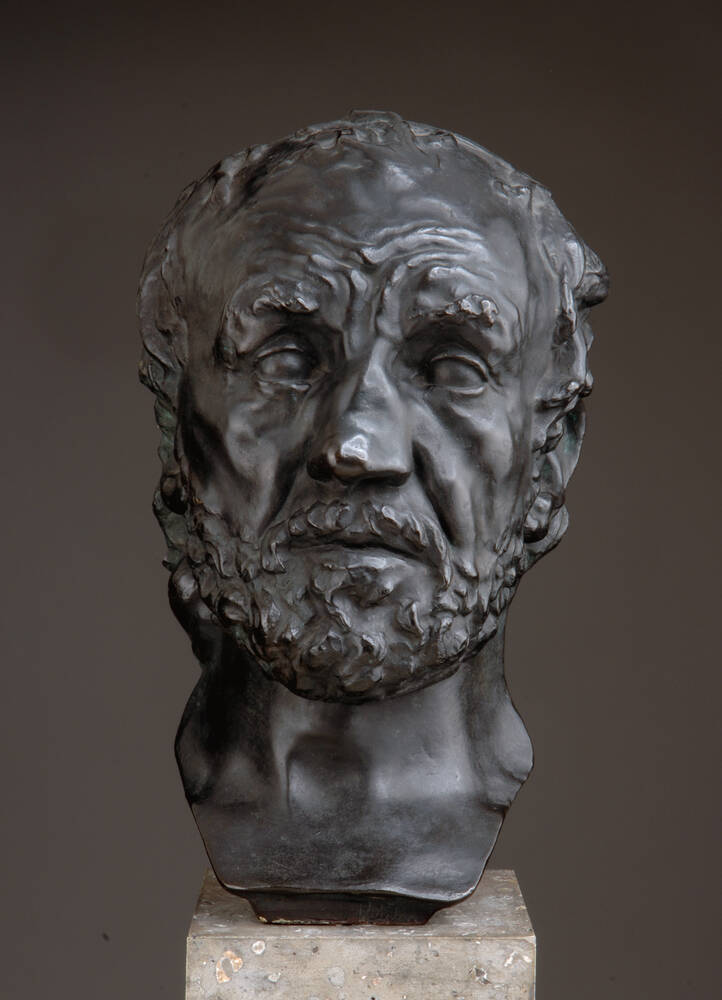

A man of flesh and blood – yet from his wrinkled forehead to the deep furrows of his cheeks and his eponymous broken nose, his face clearly bears the traces of the years. Those features suggest an eventful life. For the first time in the history of sculpture, Rodin’s figures reflect the idea of a person’s biography being incomplete, fragmentary, full of twists and turns. But who was the man with the broken nose? Here’s curator Astrid Nielsen:

“This portrait is known as portrait M.B. – initials which could stand for Monsieur Bibi, a workman at the horse market. Since Rodin’s first studio was close by, Bibi may have sat as the model for this bust. But there’s also an anecdote about this work. According to that story, the nose is out of shape because the clay model for the sculpture accidentally fell on the ground. In other words, no one can know if Monsieur Bibi really had a broken nose or not. But the initials in Portrait M.B. might also stand for Michelangelo Buonarroti. There is, after all, a well-known Renaissance portrait of Michelangelo with just such a broken nose.

That renowned Italian Renaissance artist and sculptor was one of Rodin’s most important sources of inspiration.

Incidentally, the Man with the Broken Nose was the first of Rodin’s works bought by a German Museum. In 1894, Georg Treu, then Director of the Dresden Sculpture Collection in the Albertinum, travelled to Paris. He visited Rodin in his studio and acquired the work directly from him. In Dresden, it was immediately put on public show. But at that time, Rodin’s works were quite controversial. With his modern designs, he often found himself at odds with the conservative zeitgeist of his day. After all, he did not depict distant heroic figures, but very much flesh-and-blood people – just as he has done in this work.ly bears the traces of the years. Those features suggest an eventful life. For the first time in the history of sculpture, Rodin’s figures reflect the idea of a person’s biography being incomplete, fragmentary, full of twists and turns. But who was the man with the broken nose? Here’s curator Astrid Nielsen:

“This portrait is known as portrait M.B. – initials which could stand for Monsieur Bibi, a workman at the horse market. Since Rodin’s first studio was close by, Bibi may have sat as the model for this bust. But there’s also an anecdote about this work. According to that story, the nose is out of shape because the clay model for the sculpture accidentally fell on the ground. In other words, no one can know if Monsieur Bibi really had a broken nose or not. But the initials in Portrait M.B. might also stand for Michelangelo Buonarroti. There is, after all, a well-known Renaissance portrait of Michelangelo with just such a broken nose.

That renowned Italian Renaissance artist and sculptor was one of Rodin’s most important sources of inspiration.

Incidentally, the Man with the Broken Nose was the first of Rodin’s works bought by a German Museum. In 1894, Georg Treu, then Director of the Dresden Sculpture Collection in the Albertinum, travelled to Paris. He visited Rodin in his studio and acquired the work directly from him. In Dresden, it was immediately put on public show. But at that time, Rodin’s works were quite controversial. With his modern designs, he often found himself at odds with the conservative zeitgeist of his day. After all, he did not depict distant heroic figures, but very much flesh-and-blood people – just as he has done in this work.

Further Media

Georg Treu: An archaeologist and modernity

Although not an art historian Georg Treu, then Director of the Dresden Sculpture Collection, was a fervent advocate of Rodin’s modern sculptures – or was Treu’s support for Rodin precisely because he was not an art historian? Astrid Nielsen explains:

“Georg Treu was an archaeologist. When he came to Dresden in 1881, he took over as head of the sculpture collection which, at that time, still comprised the antiquities collection and the collection of plaster casts.”

Treu had been involved in the excavations in Olympia. In Dresden, his tasks included opening a new museum for sculpture. The first thing he did when he took office was to modernise the collection of antiquities:

“During the Baroque period, the missing parts of these ancient statues had all been replaced. One of the principal tasks of Baroque sculptors was to complete damaged ancient sculptures. But when Georg Treu was training as an archaeologist, the scholarly, archaeological approach had changed totally – so he came to Dresden and removed all the Baroque additions to the ancient statues.”

Three years later, Treu opened the new Sculpture Museum here in the Albertinum. In the following years, he began to be interested in contemporary art works.

“In those days, in particular, sculpture in France was really making waves. Treu was friendly with a member of a noble Saxon family who was working at the Paris embassy. So Treu got in touch and sent him off to visit a wide range of artists’ studios there – and that was his first contact to Auguste Rodin.”

Treu was immediately enthusiastic about Rodin’s art. His eye had been trained by studying fragments of ancient sculptures – and the fragmentary is also an essential feature of Rodin’s work:

“Treu could appreciate Rodin’s treatment of individual fragments or parts of bodies, and how particular figures were dissolved from the work’s context, separated from an entire group. No doubt, Treu’s appreciation came from dealing with classical art and his readiness to accept and understand fragmentary bodies.”

- Location & Dating

- 1863/64

- Material & Technique

- Bronze

- Dimenions

- H: 39,5 cm, B: 19,5 cm, T: 15,5 cm

- Museum

- Skulpturensammlung

- Inventory number

- ZV 1288