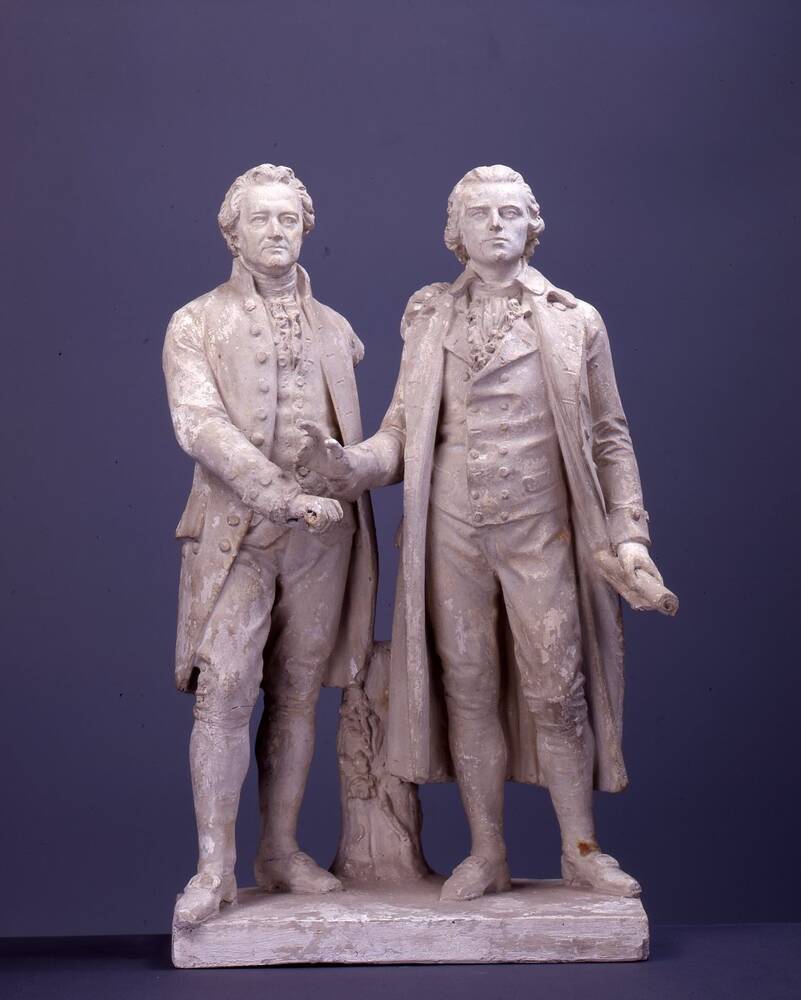

“Everyone in Germany knows this work – as do many around the world. The two figures are the writers Goethe and Schiller. Unified together as a bronze monument in the city of Weimar, they epitomise the neo-classical movement in Germany. And who was the sculptor? No one knows his name.”

But naturally our curator Astrid Nielsen knows his name – Dresden sculptor Ernst Rietschel. Here, we are showing his preliminary model for the famous monument in Weimar. This model is almost identical to the final bronze cast – though, of course, the bronze is much bigger. The only difference in the design is the laurel wreath which, in the final version, Goethe and Schiller are jointly holding.

Rietschel was a highly successful sculptor. At just 28 years old, he was appointed as a professor at the Dresden Academy of Art. But initially, the committee for the Goethe-Schiller project favoured the design by Christian Daniel Rauch in Berlin. Not only had Rauch been Rietschel’s teacher, but he was also far more famous. As was common at that time, Rauch’s proposed design portrayed Goethe and Schiller in ancient Greek robes.

"There was very traditional approach to depicting figures in memorial art at that time, with rulers, kings and so on always shown in traditional drapery – the robes of the classical world. Christian Daniel Rauch still followed that principle in his designs for the memorial sculpture ...”

But the committee decided against Rauch’s design, and in 1852 commissioned Rietschel with the work. As you can see, he presented Goethe and Schiller in contemporary clothing and as equals – with both figures the same size. In fact, Rietschel cheated here a little bit, since in real life Schiller was taller than Goethe.

Further Media

The cult of the genius and memorials in the 19th century

As curator Astrid Nielsen points out:

“The nineteenth century is generally described as THE century of monuments and memorials, a time when many new ones were set up on central squares in many cities. For example, we know of around 18 to 20 large memorials in Germany in 1800, but by the 1880s, that number had grown to 800.”

In those days, critical contemporaries called it nothing short of a monument mania. And renowned and glorious rulers found they needed to defend their place on the plinth against increasing competition:

“The new thing in the nineteenth century was that monuments and memorials were no longer solely for kings, queens and rulers, but also for luminaries in the worlds of literature, music, and so on – in other words, this was about honouring someone’s life’s work – not their inherited position, but what they had achieved. This novel idea was closely linked to the age of Enlightenment and also, of course, to a burgeoning notion of democracy where a person active in political life, or a leading light in culture and the arts, would be worthy of a memorial.”

Ernst Rietschel’s Goethe and Schiller Memorial is no doubt his most famous work, though it is far from his only one:

“Rietschel made numerous monuments and memorials, not just here in Saxony, but also, for example, the Lessing Memorial in Braunschweig, and the Luther Memorial in Worms. He is ranked as one of the founders of the Dresden school of sculpture, a leading movement in the mid-nineteenth century – especially in monumental sculpture.”

Moreover, in his monuments and memorials, Rietschel introduced an innovative and lasting trend – the figures depicted in his statues wore the costume of their own day.

O-Ton Astrid Nielsen [de_107_2_Denkmal_19Jh.mp3, 03:28-03:50]

“You can see this very easily in his Schiller and Goethe Memorial, as well as his Lessing Memorial. Previously, such figures were dressed in traditional drapery, those flowing ancient robes. Remarkably for his time, Ernst Rietschel abandoned that approach – and by adopting period costumes, created a special sense of closeness between the beholders and the figures.”

- Location & Dating

- 1852/53

- Material & Technique

- Plaster

- Dimenions

- Gesamt: H: 56,2 cm, B: 35,3 cm, T: 20,8 cm

- Museum

- Skulpturensammlung

- Inventory number

- ASN 0061