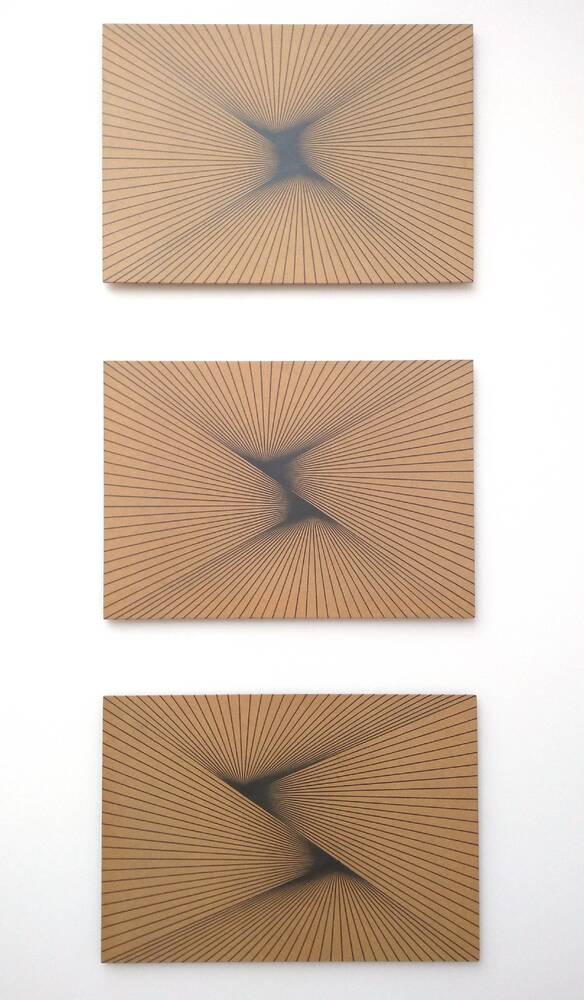

Late in life, Karl-Heinz Adler offered an explanation of his Serial Lines – a series of works started in the 1960s.

“My aim was nothing more than to produce a variety of depths by creating canyons running far apart or colliding with each other. [...] There is no secret to it, it is all rather ordinary.”

Adler’s profound and precise exploration of systematic algorithmic shapes and serial production are informed by his interest in science and technology. At the same time, these forms create a magical pictorial space of an unfathomable depth, testing our rational relationship to the world as well as our concept of space and time. As Adler once said, he viewed painting as a way of philosophically observing the world with the help of visual means.

Originally, he trained as a textile designer at a carpet factory. In the post-war period, he studied at art colleges in West Berlin and Dresden and, in 1953, became a member of the GDR’s Verband Bildender Künstler – East Germany’s Association of Visual Artists. But Adler did not really fit into the GDR system. His artistic work was always far removed from the state-approved figurative art or Socialist Realism. Above all, in his exploration of the interplay of colours and forms he became a proponent of Concrete Art, a movement merely tolerated in the GDR. In contrast, his work in architectural art was certainly welcomed. In that area, Adler is best known for the concrete modular system developed with Friedrich Kracht. From the 1970s, this system was produced industrially and integrated into façades in many places in East Germany. The modular forms also provided ornamental concrete surfaces for decorative walls to structure urban public space and enhance its aesthetic value.

Further Media

Dresden Concrete Artists

The Nazi regime condemned all avant-garde movements as “degenerate”, just as they did concrete art, a type of non-figurative painting and sculpture. After the end of the war, many artists sought to revisit and revitalise modern art. In summer 1946, the First Art Exhibition of the GDR in Dresden also held out the promise of being open to all avant-garde art movements. By late 1948, though, this policy underwent a U-turn in the Soviet zone, which later became the GDR. The new guiding principle was Socialist Realism – figurative art conveying the ideal of the socialist personality. Abstract, non-representational styles such as concrete art were rejected as “formalist” and had no place in East Germany’s official art world.

Afterwards, concrete art only existed in an artistic niche. For example, Dresden artist Hermann Glöckner, one of Germany’s most important figures in concrete art, worked alone for a long time. Removed from official art circles in East Germany, he earned a living from decorative wall décor for buildings. Concrete artists Karl-Heinz Adler and Friedrich Kracht, who both studied in Dresden, also worked in the field of ornamental architectural art. They developed a series of 12 specially-shaped concrete bricks able to be combined into diverse patterns – a modular design system integrated into many façades in the GDR. In addition, Adler and Kracht also created sculptures and fountains. East Germany’s cultural functionaries, though, failed to recognise the artistic merit of such works, solely seeing their value in terms of engineering and decoration – which at least had the advantage of taking these concrete artists off the radar of state censorship and so giving them more freedom to work. From the 1970s, there were moves to partially liberalise cultural policies in East Germany. In 1984, for instance, Hermann Glöckner, then 95 years old, was awarded the National Prize of the GDR, third class.

- Location & Dating

- 1989

- Material & Technique

- Graphite on fibreboard

- Dimenions

- 99 x 69 cm (je Tafel)

- Museum

- Galerie Neue Meister

- Inventory number

- Inv.-Nr. 2019/02