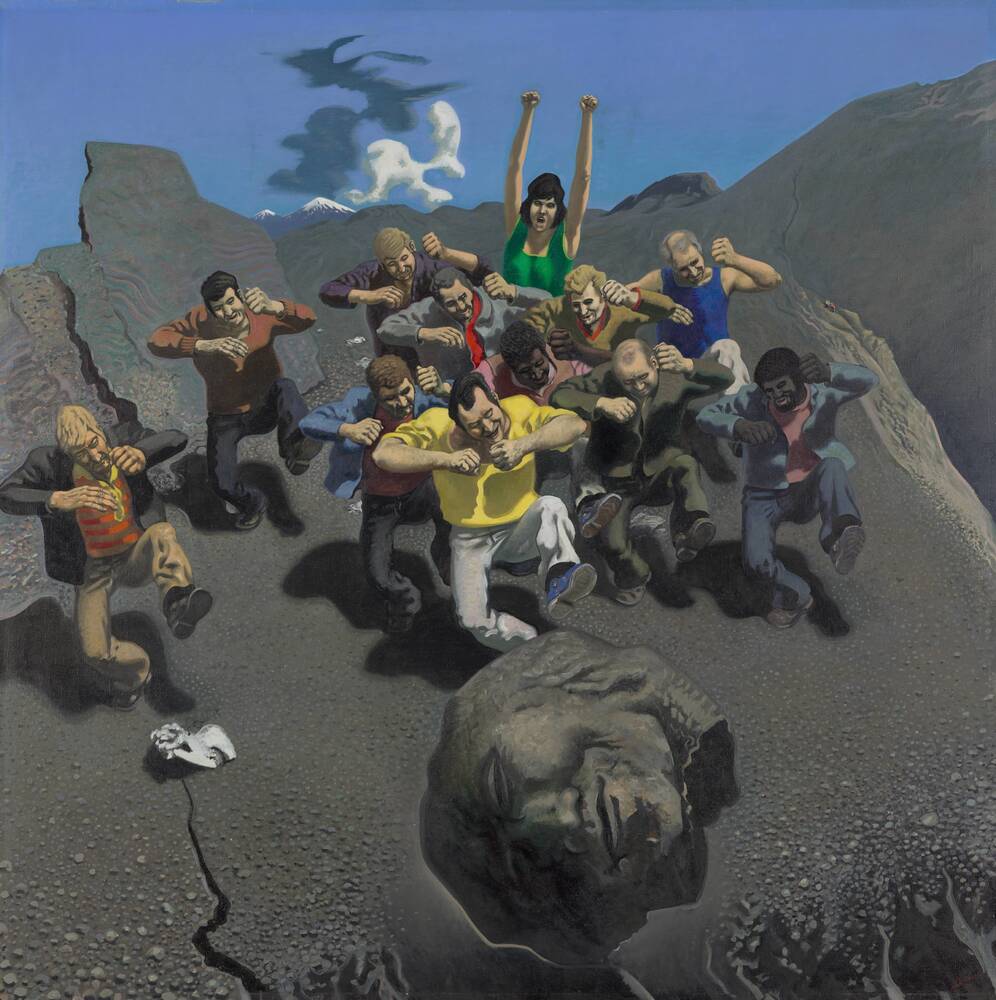

In Greek mythology, the gods thought up a particularly horrific way of punishing Sisyphus. They condemned him to roll a massive boulder up a hill – and every time it neared the summit, it rolled down and he had to start again. Was this the epitome of a hopeless task? Wolfgang Mattheuer’s Sisyphus cycle from the 1970s plays with three possible alternatives to that narrative. In the first, Sisyphus escapes his senseless fate by running away. He simply stops pushing the boulder and, with huge strides, races for the valley. In the second scene, an exuberant Sisyphus celebrates with helpers as they watch a massive stone head roll down a steep slope. The group is euphoric – have their combined efforts toppled a memorial? The landscape, though, is desolate and bleak. Barely visible in the background on the right, a tiny figure still recalls Sisyphus’s seemingly endless task.

In the third painting, Sisyphus is no longer dressed as a worker, but in a shirt and tie. Watched by three men, he is busily working a huge grey boulder with a hammer and chisel, shaping it into a clenched fist – a symbol of resistance. The scene is set in a junk yard. In the background, tall chimneys send up plumes of grey smoke into the yellow sky.

The message: rather than people simply being helpless in the face of their fate, they have to act. The paintings are packed with allusions and metaphors which can easily be read as criticising the state of affairs in the GDR – yet also offer other interpretations. As a result, Wolfgang Mattheuer was officially praised, yet secretly kept under observation by the Stasi. In West Germany, his work proved similarly difficult to categorise. There, he was initially acclaimed for his critique of the East German system, but shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall was accused of being one of the GDR’s ‘state artists’.

Together with Bernhard Heisig and Werner Tübke, Wolfgang Mattheuer belonged to the first generation of what became known as the Leipzig School.

Further Media

Leipzig School

In the 1960s, the particular style of art developing in Leipzig was dubbed the Leipzig School – and after German reunification this was followed by what became known as the New Leipzig School. The first generation primarily comprised four East German artists: Wolfgang Mattheuer, Werner Tübke, Bernhard Heisig and Willi Sitte, who actually lived and worked in Halle.

“These four artists never referred to themselves as the Leipzig School. But they were combined under that name, even though their art was very different and each of them would have dismissed the idea of belonging to such a group.”

So the Leipzig School was anything but unified stylistically. Nonetheless, these artists shared two things – first, impressive technical perfection and, second, what curator Astrid Nielsen refers to as their approach to an “art of ideas”:

“When it came to painting in Dresden and Leipzig, there was a certain competition between these two cities. Dresden was said to favour in particular the painterly, while in Leipzig the conceptual, the art of ideas, was more important – and that’s what you find too when you compare these four artists. They all convey ideas and life-worlds which, in a special way, shaped the GDR in the 1970s.”

The Leipzig School artists were also well known outside the GDR:

“In the early 1970s especially, they enjoyed a rapid rise to prominence. Not only did they significantly influence the image of East German art, but also has a major impact on how West Germany perceived the GDR.

It may also be interesting to know that these artists were allowed to travel to the West as well. They were very successful – and in contrast to other artists NOT allowed to travel, Werner Tübke in particular enjoyed various privileges, could go to Italy, and could also, for example, take part in the documenta in Kassel in 1977.”

- Location & Dating

- 1976

- Material & Technique

- Oil on canvas

- Dimenions

- 200 x 200 cm (Katalogmaß 2010) 200 x 200 cm (Katalogmaß 1987) 200 x 200 cm (Inventurmaß, 20.05.2010) 208,5 x 208 x 6,5 cm (Rahmenmaß, Tobias Lange, 20.05.2010)

- Museum

- Galerie Neue Meister

- Inventory number

- Inv.-Nr. 81/02