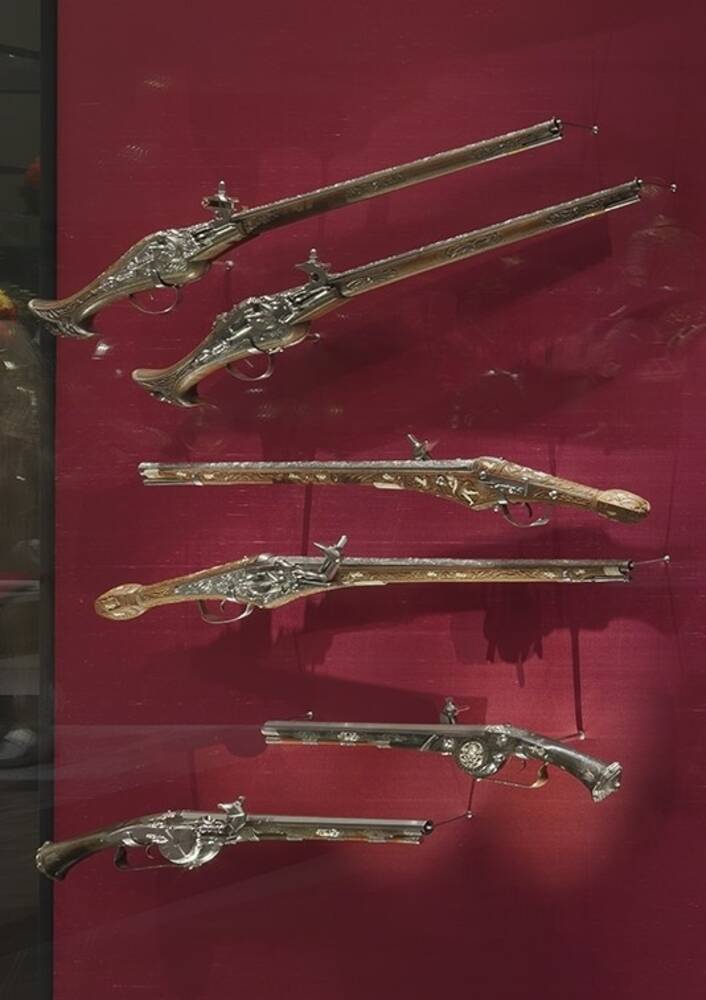

The two wheel-lock pistols you see here are a matching pair. They were made some thirty years after the gold-plated pistols that were given to Elector Christian I as a present and later preserved in the Dresden Armoury. You’ll notice that these weapons have long barrels, walnut butts, and that they bear the Electoral coat of arms with the Latin inscription: Scopus Vitae Meae Christus – “Christ is my life’s goal”.

That was the motto of Johann Georg I, whose reign began in 1611. The pistols were especially made for him and were originally part of a larger gift that included a silver-plated key for winding the wheel-lock and a silver powder flask. However, the pièce de résistance in this gift was a grey stallion with an embroidered saddle and trappings. There was also a pair of pistol holsters and a little bag of gun accessories, a cartridge bag, a leather-covered box containing a variety of miniature tools, a gold cloth, a wide belt and baldrics. Unfortunately, we don’t know who made these pistols, in spite of the initials G E engraved at the end of the barrels. We do know, however, who made this generous gift to the Elector.

It was the city of Leipzig. And we even know the date the gift was presented. It was 2 April 1623. Leipzig had good reason to shower the Elector with gifts. The inventory doesn’t detail the background facts, but the circumstances speak for themselves. On taking office, Johann Georg I had drastically raised the tax on goods sold at fairs. That was disastrous for the city of Leipzig, which was famous for its fair.

As a result of the new tax, foreign traders stayed away and the city’s revenue shrank. The Elector then had second thoughts. In 1619 he rescinded the tax, and trade immediately flourished again. So this gift was the city’s way of saying thank you to the Elector for ensuring its future prosperity.

These two pistols are lavishly decorated with silver inlays, motifs of trophies and silver medallions. The openwork, gilded lock plate is decorated with birds and fabulous creatures. The medallions bear inscriptions. However, the scenes they depict are not flights of fancy, but mirror the harsh realities that were facing Europe at that time.

Saxony had been drawn into the Thirty Years‘ War in spite of Johann Georg I’s efforts to keep his territory out of the brutal conflict. The inscriptions on the medallions record various battles and sieges of that time: events that occurred in or before 1622, when the pistols were made.

If you would like to find out more, please listen to the audio under further media.

Further Media

Wheel-lock pistols were the nobleman’s preferred weapon in the seventeenth century, and an extremely fashionable gift. The wheel-lock pistol marked a considerable technical advance on previous firearms, which were ignited by means of a burning fuse. It fired without producing fumes, which was a great advantage when hunting, and it worked just as well in the rain. But a wheel-lock is a complex construction and was initially very expensive.

A wheel-lock’s main component is a steel disc with a striated edge. This wheel was wound with a key so that it was under tension. In the case of the pair of pistols owned by Elector Johann Georg I that you can see on display here, this was done using the silver-plated key included among the accessories. The ignition worked on the same principle as a modern cigarette lighter. When you pulled the trigger, the wheel rotated against iron pyrites, and this friction produced a spark. That ignited the powder in the pan, which then burnt through a vent in the base of the barrel and exploded the gunpowder in the air cell, thereby expelling the bullet.

As it happens, the appearance of many items you see here has not only been altered by time. That includes these wheel-lock pistols. In the nineteenth century, collectors of historical firearms were often more interested in the beauty of the objects than in their authenticity.

As a result, they frequently damaged those they acquired. Old pistols were continuously being cleaned, leached and polished to make them look new again. That destroyed the patina forever, and individual parts often no longer matched. If a part was missing, it was replaced without regard to the origin or date of the original. However, in this respect, too, Dresden maintained the highest of standards: everything stored in the Rüstkammer was spared such vandalism. The collection was in the royal family’s sole possession for centuries and obsolete objects were preserved with the utmost care. Even when the contents of the collection were removed from the Rüstkammer during the Second World War and taken to a place of safety, many items remained entirely unscathed. That’s why it was possible to restore the objects on display here in the Riesensaal to such a high standard. Original parts have been cleaned and secured, but no new parts have been added, except in

very few exceptional cases. It was a blessing for our conservators, but it’s also a treat for our visitors. There’s hardly any other collection – worldwide – with such well-preserved objects as you’ll find in the Dresden Armoury.