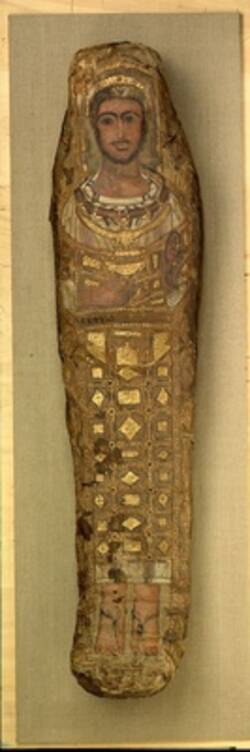

These Egyptian mummies may well have been the first ever seen in Europe. A traveller brought them to Rome in the seventeenth century, and later they were acquired by August the Strong. Unusually, the mummies do not have death masks, but portraits of the deceased painted directly onto the linen bandages. The high status of the figures is underlined by the exquisite gold jewellery. Both of these figures lived in the third or fourth century AD in the major city of Memphis, at that time part of the Roman Empire. They are also painted as Romans, yet were among the last followers of the Ancient Egyptian gods, venerated for thousands of years. Their beliefs are evident from the traditional vulture goddess Nekhbet* protecting the man’s chest. In Memphis, many of their neighbours would have worshipped the Roman deities, or practiced the Jewish or Christian faiths.

Further Media

Greek historian Herodotus has left the most extensive contemporary description of the mummification process. Herodotus travelled through ancient Egypt in the fifth century BC. His writings provide details on the various methods used by the Egyptians to mummify their dead:

“As much as possible of the brain is extracted through the nostrils with an iron hook, and what the hook cannot reach is rinsed out with drugs; next the flank is laid open with a flint knife and the whole contents of the abdomen removed; the cavity is then thoroughly cleansed and washed out, first with palm wine and again with an infusion of powdered spices. After that, it is filled with pure bruised myrrh, cassia, and every other aromatic substance with the exception of frankincense, and sewn up again, after which the body is placed in natrum, covered over entirely, for seventy days – never longer. At the end of this period, which must not be exceeded, the body is washed and then wrapped from head to foot in linen cut into strips and smeared on the underside with gum …”

In 1615 Pietro della Valle, an erudite and wealthy Roman, brought the mummies from Egypt to Europe. While on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, della Valle stopped off at the pyramids near Cairo.

In the Arab world, the village of Saqqara near Cairo was renowned as a centre trading a particular kind of goods – mummies. But the embalmed mummies were not just much sought after as precious antiquities, but also as a raw material for medicinal remedies. They were a source of a tar-like substance called mumia vera aegyptica. ‘Mummy’ is derived from the Arabic word ‘mummiya’, which actually refers to a type of bitumen. Mumia vera was a mixture of resins, ointments, oils and bitumen used to embalm bodies. Over time, the mixture became solid. In powder or crumbled form, mumia vera could be sold for a high price. Soon, it was also available from European apothecaries, especially since reputedly it could cure all manner of illnesses, or at least ease their symptoms.

On his visit to Egypt, Pietro della Valle was on hand when locals excavated the mummies on show here. He even had himself lowered into the tomb. While he was there, he also made provisions for his own first-aid travel kit by breaking off several chunks from a third mummy.

- Location & Dating

- Late 3rd to mid- 4th cent. CE

- Material & Technique

- Linen, stucco, painted and gilt, mummified body

- Dimenions

- L: 175,0 cm, H: 29,5 cm, B: 40,0 cm

- Museum

- Skulpturensammlung

- Inventory number

- Aeg 777