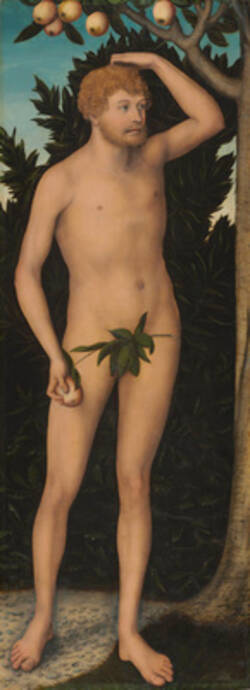

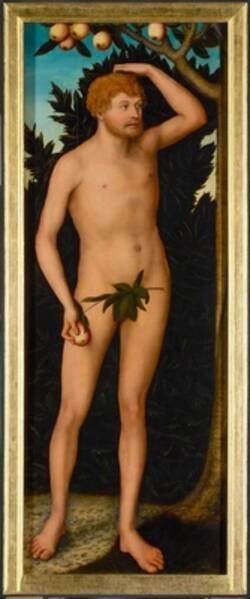

The first man and woman were frequent subjects for the Cranachs. While generally similar, there are major differences in the details. This version by Cranach the Younger combines both religious and erotic references. Standing beneath the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, and in harmony with nature in the Garden of Eden, the two nude figures look towards each other: Eve seductively, having been led astray by evil in the form of a serpent, Adam still considering whether to taste the apple.

Further Media

In the early sixteenth century, Albrecht Dürer modelled his Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden on the ideals of beauty in the classical world – and, in doing so, he created something completely new. A few years later, his painting and print served as the inspiration for Lucas Cranach the Elder – but he did not just copy Dürer. For Cranach, the harmony of the entire composition, a certain elegance and soft contour lines were more important than ideal proportions and anatomical accuracy. So in Cranach’s figures, Adam’s legs appear slightly too long for his body, and the position of Eve’s feet seems unnatural.

In our version from 1531, Cranach only signed the panel showing Adam. Just above Adam’s feet, you can find Cranach’s signature – a winged serpent with a crown on its head and bearing a ring in its mouth. The year – 1531 – is set above the serpent.

Frederick the Wise, Elector of Saxony, conferred a coat of arms on his court artist Cranach in 1508. The coat of arms shows a crowned serpent with a ring in its mouth. Afterwards, Cranach not only adopted an elaborated form of the serpent as his signature, but turned it into his workshop’s trademark. Unfortunately, though, his trademark was not always applied systematically. Not only did the Cranach workshop produce signed and unsigned works, but a winged serpent is not even unequivocal proof that a painting was completely or mainly an autograph work by Cranach or one of his sons.

Incidentally, the Eve panel by Lucas Cranach the Younger is signed at the bottom right corner.

From the mid-1520s, Lucas Cranach the Elder built up a thriving workshop in Wittenberg, the residence of Friederich the Wise. Exceptionally creative and with considerable business acumen, Cranach developed techniques for speeding up the painting process and introduced standardised workflows. If subjects were much in demand, he produced paintings of them in several versions – an approach continued by Cranach’s son and workshop assistants after his death.

The paintings of Adam and Eve can be divided into two types – first, with the figures against a monotone dark background and, second, against a landscape. Our collection includes both these versions. Yet the different versions share many common features. Adam and Eve are nearly life-size, slim, and look remarkably similar. They are also all painted on limewood panels around 170 centimetres high. Moreover each panel always has the cropped trunk of an apple tree on one side as a connection to its companion. And in both versions, the cunning smiling snake has already reached it goal – Eve has plucked the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge, has bitten into an apple and, with her right hand, holds it out to Adam. In the biblical account of the Fall of Man, as this is known, Eve has the active role. When they taste the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, Adam and Eve realise they are naked and cover their loins with leafy twigs.

Aside from the background and the direction Eve is looking, there are other differences too. Lucas Cranach the Younger painted Adam and Eve as a young couple. The two figures look towards each other subdued, rather embarrassed. Adam scratches his head indecisively; the position of Eve’s arms seems rather unnatural. In Lucas Cranach the Elder’s Adam and Eve, the atmosphere is quite different. His figures are more mature. Adam already has some touches of silver in his curly red hair. Adam and Eve also seem to share a strong premonition of the events to come. Adam looks at Eve with a rather severe, almost grim expression, while her irresistible, inscrutable gaze casts us under its spell.

- Location & Dating

- after 1537

- Material & Technique

- Oil on limewood panel

- Dimenions

- 172,5 x 63,3 cm

- Museum

- Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

- Inventory number

- Gal.-Nr. 1916 A