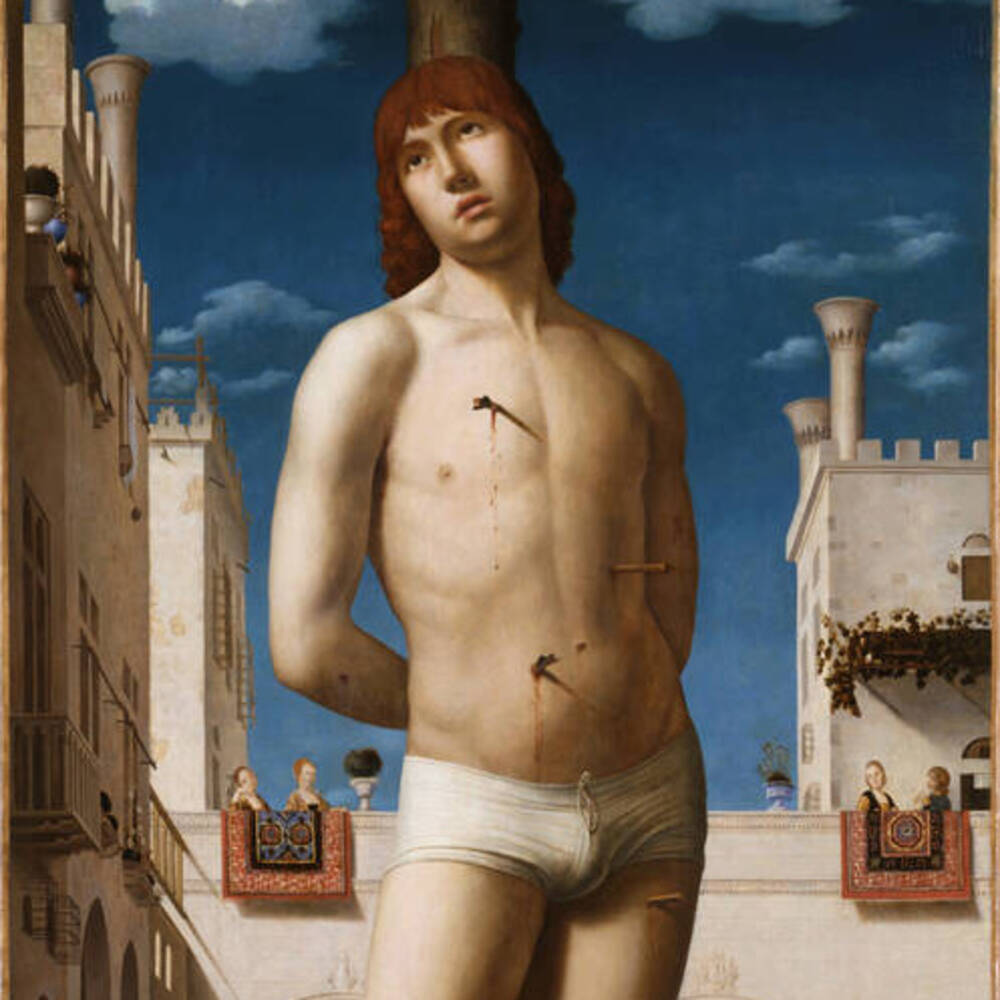

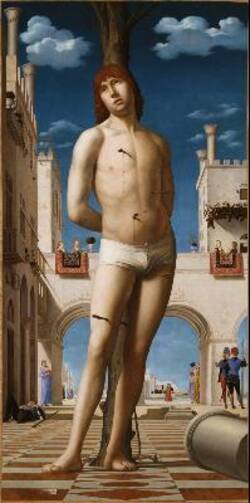

Renaissance artists mostly studied the beauty and proportions of the human form by observing classical sculptures. Thus, the detailed rendering of the body of St Sebastian is reminiscent of antique marble statues. Another typical aspect is that the martyred saint appears to be alive. The saint was shot with arrows on account of his Christian faith. His heavenward gaze reflects his certainty of reward in the afterlife. This work was painted for the altar of the Confraternity of St Roch in Venice.

Further Media

According to legend, Saint Sebastian lived in the third century AD. Originally a high-ranking Roman soldier, he commanded the bodyguard of Emperor Diocletian. But Sebastian’s faith was revealed when he helped Christians who were suffering. He was put on trial and sentenced to death. His executioners took him to a field, shot him with arrows and left him for dead – but he was still alive. A pious widow found him and nursed him back to health. Revived, Sebastian went straight to Emperor Diocletian and publicly accused him of his cruelties in persecuting Christians. Diocletian responded by ordering Sebastian to be beaten to death – and this time, the saint did not survive. His body was thrown into the common sewer so no one could find him and make him a martyr for his faith. But saints have faculties normal mortals don’t possess. Sebastian appeared to a Christian woman in a dream, showing her where to find his body.

From early on, Saint Sebastian was venerated as a deliverer from the plague, since the plague was also thought to spread by invisible arrows shot through the air. Sebastian’s role as a deliverer from the plague was also the reason for Antonello’s painting. Venice had suffered a plague epidemic wiping out over 15 per cent of the city’s population. With this painting of Sebastian, Antonello’s Venetian customers sought to invoke the saint’s protection against the plague.

This painting of Saint Sebastian also has another message – as a showpiece for Antonello’s skills as an artist.

Antonello has composed the work with perfect single-point perspective – as you can tell from the edges of the rows of tiles on the ground, all aligned with the same vanishing point. This way of depicting space had only been discovered some 50 years before. The complex patterns on the tiles also allow Antonello to demonstrate just how well he had mastered this style of perspective. That’s also for the reason for the unusual figure of a soldier lying on the ground to the left, apparently asleep. Depicting the human body with spatial foreshortening was considered especially difficult – but Antonello shows this is a challenge he can easily meet. The toppled column on the ground is another testament to Antonello's command of linear perspective. It is complicated enough to convincingly render a foreshortened cylindrical form, but here the column is also slightly twisted away from the vanishing point. Yet again, though, Antonello shows his mastery of perspective.

Originally Antonello came from Sicily. When he painted this work he had already spent a year in Venice and familiarised himself with the abilities of artists there. As already mentioned, his painting was commissioned by a charitable Confraternity in Venice. Evidently, Antonello took that as a chance to throw down the gauntlet to his fellow artists in the city by saying: Look! I can do just what you can – but better!

- Location & Dating

- c. 1478

- Material & Technique

- Oil on panel, transferred to canvas

- Dimenions

- 171 x 85,5 cm

- Museum

- Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

- Inventory number

- Gal.-Nr. 52