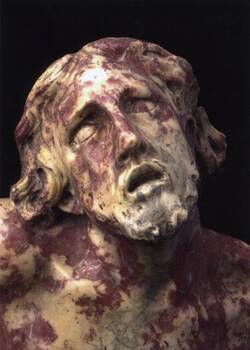

In his last of at least three explorations of the theme of Christ's martyrdom, Permoser relied entirely on the natural colour of the special Salzburg marble for the depiction of the cruelly maltreated body and dispensed with any sculptural depiction of wounds. He used the scourging column for a relief showing the Saviour collapsing at prayer on the Mount of Olives on the eve of the Passion, surrounded by angels. Permoser's self-portrait and signature can be found on the reverse.

Further Media

Christian subjects have different functions from mythological scenes or a depiction of historical events. Where works of mythology or history are illustrative, religious images aim to address a sense of spirituality and empathy. This group of devotional images also includes works depicting the scourging of Christ. Initially, the scourging of Christ belonged to the set sequence of stations in the Passion of Christ, the narrative of Christ’s trial, torture and crucifixion. In the late Middle Ages, though, painters and sculptures began to take it as a subject for independent works

showing the scourged and bloodied Christ before he is sentenced to crucifixion.

In a thirteenth-century devotional work, it says “And so he stood upright at the column, his hands tied, until the next morning” – which would be the day of Christ’s crucifixion. His clothes ripped from him, Christ’s body is freezing inside the cold, clammy walls of the prison and scarred with deep wounds and bruises. Greater wretchedness is almost inconceivable, even looking at the scene is an effort – which is intended precisely to initiate a devotional meditation on Christ’s suffering. Jesus Christ is the naked image of the invisible God. He is God become flesh, and through his wounds, we find eternal salvation.

This statue is one of the much-acclaimed masterpieces in Permoser’s late works. Here, he created a work which, in the eyes of his contemporaries, deserved nothing but the highest praise. After all, Christ’s bleeding wounds were rendered solely by the stone’s natural colour. To achieve that effect, Permoser chose a particular material – Plassen limestone from upper Austria. This type of marble crumbles easily, and is difficult to work. But Permoser was experienced in sculpting very diverse materials. His ideal was to fuse art and nature so it was impossible to differentiate the natural from what was added by human hand. If you look at the sculpture carefully, you’ll notice how Christ’s body is absolutely smooth – and so the wounds are not sculpted individually. Instead, Permoser worked the stone to render Christ’s ravaged skin so realistically it is almost painful to look at.

Permoser had been experimenting with this idea for some time. You can see an earlier version of Christ at the Column directly adjacent or as an image on your device. On that figure, which dates from three years earlier, Permoser sculpted parts of the marble to create three-dimensional drops of blood trickling from Christ’s wounds. Under his maltreatment, Christ’s exhausted body twists and turns. In the later version, though, Permoser sculpts Christ standing still. Although the pain twists his body into an almost unnatural S-shape, Christ does not move. He gazes devoutly up to heaven, knowing full well that his real martyrdom, his death on the cross, is still to come.

- Location & Dating

- Salzburg, 1728

- Material & Technique

- Marble from Untersberg

- Dimenions

- H: 81 cm, B: 27 cm, T: 25 cm

- Museum

- Skulpturensammlung

- Inventory number

- ZV 4090